- Home

- Clive Barker

Books of Blood Vol 2 Page 14

Books of Blood Vol 2 Read online

Page 14

Packard grinned across to Jebediah at the wheel. "Sure as shit," he said again. "We're going to blow them all to Kingdom Come."

From the back of the car, Miss Kooker leaned out the window; she was smoking a cigar.

"Seems we owe you an apology, Gene," she said, offering an apology for a smile. He's still a sot, she thought; marrying that fat-bottomed whore was the death of him. What a waste of a man.

Eugene's face tightened with satisfaction.

"Seems you do."

"Get in one of them cars behind," said Packard, "you and Lucy both; and we'll fetch them out of their holes like snakes —"

"The've gone towards the hills," said Eugene.

"That so?"

"Took my boy. Threw my house down."

"Many of them?"

"Dozen or so."

"OK Eugene, you'd best get in with us." Packard ordered a cop out of the back. "You're going to be hot for them bastards, eh?"

Eugene turned to where Lucy had been standing.

"And I want her tried —" he said.

But Lucy was gone, running off across the desert: doll-sized already.

"She's headed off the road," said Eleanor. "She'll kill herself."

"Killing's too good for her," said Eugene, as he climbed into the car. "That woman's meaner than the Devil himself."

"How's that, Gene?"

"Sold my only son to Hell, that woman —"Lucy was erased by the heat-haze.

"— to Hell."

"Then let her be," said Packard. "Hell'll take her back, sooner or later."

Lucy had known they wouldn't bother to follow her. From the moment she'd seen the car lights in the dust-cloud, seen the guns, and the helmets, she knew she had little place in the events ahead. At best, she would be a spectator. At worst, she'd die of heatstroke crossing the desert, and never know the upshot of the oncoming battle. She'd often mused about the existence of the creatures who were collectively Aaron's father. Where they lived, why they'd chosen, in their wisdom, to make love to her. She'd wondered also whether anyone else in Welcome had knowledge of them. How many human eyes, other than her own, had snatched glimpses of their secret anatomies, down the passage of years? And of course she'd wondered if there would one day come a reckoning time, a confrontation between one species and the other. Now it seemed to be here, without warning, and against the background of such a reckoning her life was as nothing.

Once the cars and bikes had disappeared out of sight, she doubled back, tracing her footmarks in the sand, ‘til she met the road again. There was no way of regaining Aaron, she realized that. She had, in a sense, merely been a guardian of the child, though she'd borne him. He belonged, in some strange way, to the creatures that had married their seeds in her body to make him. Maybe she'd been a vessel for some experiment in fertility, and now the doctors had returned to examine the resulting child. Maybe they had simply taken him out of love. Whatever the reasons she only hoped she would see the outcome of the battle. Deep in her, in a place touched only by monsters, she hoped for their victory, even though many of the species she called her own would perish as a result.

In the foothills there hung a great silence. Aaron had been set down amongst the rocks, and they gathered around him eagerly to examine his clothes, his hair, his eyes, his smile.

It was towards evening, but Aaron didn't feel cold. The breaths of his fathers were warm, and smelt, he thought, like the interior of the General Supplies Emporium in Welcome, a mingling of toffee and hemp, fresh cheese and iron. His skin was tawny in the light of the diminishing sun, and at his zenith stars were appearing. He was not happier at his mother's nipple than in that ring of demons.

At the toe of the foothills Packard brought the convoy to a halt. Had he known who Napoleon Bonaparte was, no doubt he would have felt like that conqueror. Had he known that conqueror's life-story, he might have sensed that this was his Waterloo: but Josh Packard lived and died bereft of heroes.

He summoned his men from their cars and went amongst them, his mutilated hand tucked in his shirt for support. It was not the most encouraging parade in military history. There were more than a few white and sickly-pale faces amongst his soldiers, more than a few eyes that avoided his stare as he gave his orders.

"Men," he bawled.

(It occurred to both Kooker and Davidson that as sneak-attacks went this would not be amongst the quietest.)

"Men — we've arrived, We're organized, and we've got God on our side. We've got the best of the brutes already, understand?"

Silence; baleful looks; more sweat.

"I don't want to see one jack man of you turn your heel and run, ‘cause if you do and I set my eyes on you, you'll crawl home with your backside shot to Hell!"

Eleanor thought of applauding; but the speech wasn't over.

"And remember, men," here Packard's voice dropped to a conspiratorial whisper, "these divils took Eugene's boy Aaron not four hours past. Took him fairly off his mother's tit, while she was rocking him to sleep. They ain't nothing but savages, whatever they may look like. They don't give a mind to a mother, or a child, or nothing. So when you get up close to one you just think how you'd have felt if you'd been taken from your mother's tit-"

He liked the phrase ‘mother's tit'. It said so much, so simply. Momma's tit had a good deal more power to move these men than her apple pie.

"You've nothing to fear but seeming less than men, men."

Good line to finish on.

"Get on with it."

He got back into the car. Someone down the line began to applaud, and the clapping was taken up by the rest of them. Packard's wide red face was cleft with a hard, yellow smile.

"Wagons roll!" he grinned, and the convoy moved off into the hills.

Aaron felt the air change. It wasn't that he was cold: the breaths that warmed him remained as embracing as ever. But there was nevertheless an alteration in the atmosphere: some kind of intrusion. Fascinated, he watched his fathers respond to the change: their substance glinting with new colours, graver, warier colours. One or two even lifted their heads as if to sniff the air.

Something was wrong. Something, someone, was coming to interfere with this night of festival, unplanned and uninvited. The demons knew the signs and they were not unprepared for the eventuality. Was it not inevitable that the heroes of Welcome would come after the boy? Didn't the men believe, in their pitiable way, that their species was born out of earth's necessity to know itself, nurtured from mammal to mammal until it blossomed as humanity?

Natural then to treat the fathers as the enemy, to root them out and try to destroy them. A tragedy really: when the only thought the fathers had was of unity through marriage, that their children should blunder in and spoil the celebration.

Still, men would be men. Maybe Aaron would be different, though perhaps he too would go back in time into the human world and forget what he was learning here. The creatures who were his fathers were also men's fathers: and the marriage of semen in Lucy's body was the same mix that made the first males. Women had always existed: they had lived, a species to themselves, with the demons. But they had wanted playmates: and together they had made men.

What an error, what a cataclysmic miscalculation. Within mere eons, the worst rooted out the best; the women were made slaves, the demons killed or driven underground, leaving only a few pockets of survivors to attempt again that first experiment, and make men, like Aaron, who would be wiser to their histories. Only by infiltrating humanity with new male children could the master race be made milder. That chance was slim enough, without the interference of more angry children, their fat white fists hot with guns.

Aaron scented Packard and his stepfather, and smelling them, knew them to be alien. After tonight they would be known dispassionately, like animals of a different species. It was the gorgeous array of demons around him he felt closest to, and he knew he would protect them, if necessary, with his life.

Packard's car led the attack. The wave of vehic

les appeared out of the darkness, their sirens blaring, their headlights on, and drove straight towards the knot of celebrants. From one or two of the cars terrified cops let out spontaneous howls of terror when the full spectacle came into view, but by that time the attack force was committed. Shots were fired. Aaron felt his fathers close around him protectively, their flesh now darkening with anger and fear.

Packard knew instinctively that these things were capable of fear, he could smell it off them. It was part of his job to recognize fear, to play on it, to use it against the miscreant. He screeched his orders into his microphone and led the cars into the circle of demons. In the back of one of the following cars Davidson closed his eyes and offered up a prayer to Yahweh, Buddha and Groucho Marx. Grant me power, grant me indifference, grant me a sense of humour. But nothing came to assist him: his bladder still bubbled, and his throat still throbbed.

Ahead, the shriek of brakes. Davidson opened his eyes (just a slit) and caught sight of one of the creatures wrapping its purple-black arm around Packard's car and lifting it into the air. One of the back doors flung open and a figure he recognized as Eleanor Kooker fell the few feet to the ground followed closely by Eugene. Leaderless, the cars were in a frenzy of collisions — the whole scene partially eclipsed by smoke and dust. There was the sound of breaking windscreens as cops took the quick way out of their cars; the shrieks of crumpling hoods and sheered off doors. The dying howl of a crushed siren; the dying plea of a crushed cop.

Packard's voice was clear enough, however, howling orders from his car even as it was lifted higher into the air, its engine revving, its wheels spinning foolishly in space. The demon was shaking the car as a child might a toy until the driver's door opened and Jebediah fell to the ground at the creature's skirt of skin. Davidson saw the skirt envelop the broken-backed deputy and appear to suck him into its folds. He could see too how Eleanor was standing up to the towering demon as it devoured her son.

"Jebediah, come out of there!" she shrieked, and fired shot after shot into his devourer's featureless, cylindrical head.

Davidson got out of the car to see better. Across a clutter of crashed vehicles and blood-splattered hoods he could make the whole scene out more plainly. The demons were sloping away from the battle, leaving this one extraordinary monster to hold the bridgehead. Quietly Davidson offered up a prayer of thanks to any passing deity. The divils were disappearing. There's be no pitched battle: no hand-to-tentacle fight. The boy would be simply eaten alive, or whatever they planned for the poor little bastard. Indeed, couldn't he see Aaron from where he stood? Wasn't that his frail form the retreating demons were holding so high, like a trophy?

With Eleanor's curses and accusations in their ears the sheltering cops began to emerge from their hiding-places to surround the remaining demon. There was, after all, only one left to face, and it had their Napoleon in its slimy grip. They let off volley upon volley into its creases and tucks, and against the impartial geometry of its head, but the divil seemed unconcerned. Only when it had shaken Packard's car until the Sheriff rattled like a dead frog in a tin can did it lose interest and drop the vehicle. A smell of gasoline filled the air, and turned Davidson's stomach.

Then a cry: "Heads down!"

A grenade? Surely not; not with so much gasoline on the—Davidson fell to the floor. A sudden silence, in which an injured man could be heard whimpering somewhere in the chaos, then the dull, earth-rocking thud of the erupting grenade.

Somebody said Jesus Christ — with a kind of victory in his voice.

Jesus Christ. In the name of... for the glory of. .

The demon was ablaze. The thin tissue of its gasoline soaked skirt was burning; one of its limbs had been blown off by the blast, another partially destroyed; thick, colourless blood splashed from the wounds and the stump. There was a smell in the air like burnt candy: the creature was clearly in an agony of cremation. Its body reeled and shuddered as the flames licked up to ignite its empty face, and it stumbled away from its tormentors, not sounding its pain. Davidson got a kick out of seeing it burn: like the simple pleasure he had from putting the heel of his boot in the centre of a jelly-fish. Favourite summer-time occupation of his childhood. In Maine: hot afternoons: spiking men-o'-war.

Packard was being dragged out of the wreckage of his car. My God, that man was made of steel: he was standing upright and calling his men to advance on the enemy. Even in his finest hour, a flake of fire dropped from the flowering demon, and touched the lake of gasoline Packard was standing in. A moment later he, the car, and two of his saviours were enveloped in a billowing cloud of white fire. They stood no chance of survival: the flames just washed them away. Davidson could see their dark forms being wasted in the heart of the inferno, wrapped in folds of fire, curling in on themselves as they perished.

Almost before Packard's body had hit the ground Davidson could hear Eugene's voice over the flames.

"See what they've done? See what they've done?"

The accusation was greeted by feral howls from the cops. "Waste them!" Eugene was screaming. "Waste them!"

Lucy could hear the noise of the battle, but she made no attempt to go in the direction of the foothills. Something about the way the moon was suspended in the sky, and the smell on the breeze, had taken all desire to move out of her. Exhausted, and enchanted, she stood in the open desert, and watched the sky.

When, after an age, she brought her gaze back down to fix on the horizon, she saw two things that were of mild interest. Out of the hills, a dirty smudge of smoke, and the edge of her vision in the gentle night light, a line of creatures, hurrying away from the hills. She suddenly began to run.

It occurred to her, as she ran, that her gait was sprightly as a young girl's, and that she had a young girl's motive: that is, she was in pursuit of her lover.

In an empty stretch of desert, the convocation of demons simply disappeared from sight. From where Lucy was standing, panting in the middle of nowhere, they seemed to have been swallowed up by the earth. She broke into a run again. Surely she could see her son and his fathers once more before they left forever? Or was she, after all her years of anticipation, to be denied even that?

In the lead car Davidson was driving, commandeered to do so by Eugene, who was not at present a man to be argued with. Something about the way he carried his rifle suggested he'd shoot first and ask questions later; his orders to the straggling army that followed him were two parts incoherent obscenities to one part sense. His eyes gleamed with hysteria: his mouth dribbled a little. He was a wild man, and he terrified Davidson. But it was too late now to turn back: he was in cahoots with the man for this last, apocalyptic pursuit.

"See, them black-eyed sons of bitches don't have no fucking heads," Eugene was screaming over the tortured roar of the engine. "Why you taking this track so slow, boy?"

He jabbed the rifle in Davidson's crotch.

"Drive, or I'll blow your brains out."

"I don't know which way they've gone," Davidson yelled back at Eugene.

"What you mean? Show me!"

"I can't show you if they've disappeared."

Eugene just about appreciated the sense of the response. "Slow down, boy." He waved out of the car window to slow the rest of the army.

"Stop the car — stop the car!"

Packard brought the car to a halt.

"And put those fucking lights out. All of you!" The headlights were quenched. Behind, the rest of the entourage followed suit.

A sudden dark. A sudden silence. There was nothing to be seen or heard in any direction. They'd disappeared, the whole cacophonous tribe of demons had simply vanished into the air, chimerical.

The desert vista brightened as their eyes became accustomed to the gleam of the moonlight. Eugene got out of the car, rifle still at the ready, and stared at the sand, willing it to explain.

"Fuckers," he said, very softly.

Lucy had stopped running. Now she was walking towards the line of cars. It was all o

ver by now. They had all been tricked: the disappearing act was a trump card no-one could have anticipated.

Then, she heard Aaron.

She couldn't see him, but his voice was as clear as a bell; and like a bell, it summoned. Like a bell, it rang out: this is a time of festival: celebrate with us.

Eugene heard it too; he smiled. They were near after all.

"Hey!" the boy's voice said. "Where is he? You see him, Davidson?" Davidson shook his head. Then —"Wait! Wait! I see a light — look, straight ahead awhile."

"I see it."

With exaggerated caution, Eugene motioned Davidson back into the driver's seat.

"Drive, boy. But slowly. And no lights."

Davidson nodded. More jelly-fish for the spiking, he thought; they were going to get the bastards after all, and wasn't that worth a little risk? The convoy started up again, creeping forward at a snail's pace.

Lucy began to run once more: she could see the tiny figure of Aaron now, standing on the lip of a slope that led under the sand. The cars were moving towards it.

Seeing them approaching, Aaron stopped his calls and began to walk away, back down the slope. There was no need to wait any longer, they were following for certain. His naked feet made scarcely a mark in the soft-sanded incline that led away from the idiocies of the world. In the shadows of the earth at the end of that slope, fluttering and smiling at him, he could see his family.

"He's going in," said Davidson.

"Then follow the little bastard," said Eugene. "Maybe the kid doesn't know what he's doing. And get some light on him."

The headlights illuminated Aaron. His clothes were in tatters, and his body was slumped with exhaustion as he walked.

A few yards off to the right of the slope Lucy watched as the lead car drove over the lip of the earth and followed the boy down, into—"No," she said to herself, "don't."

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

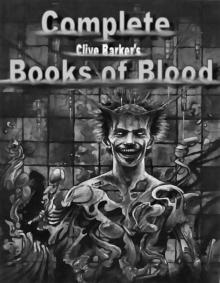

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

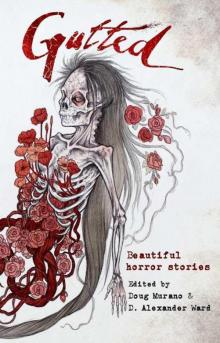

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

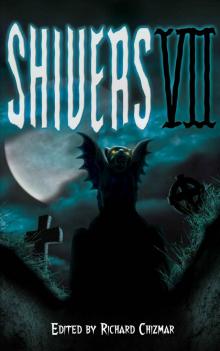

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

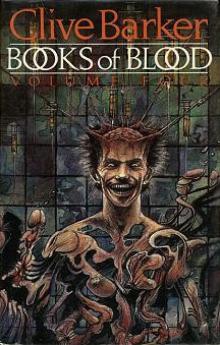

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4