- Home

- Clive Barker

Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 Read online

Books of Blood Vol 2

Clive Barker

Clive Barker

Books of Blood Vol 2

Every body is a book of blood;

Wherever We're opened, We're red.

DREAD

THERE IS NO delight the equal of dread. If it were possible to sit, invisible, between two people on any train, in any waiting room or office, the conversation overheard would time and again circle on that subject. Certainly the debate might appear to be about something entirely different; the state of the nation, idle chat about death on the roads, the rising price of dental care; but strip away the metaphor, the innuendo, and there, nestling at the heart of the discourse, is dread. While the nature of God, and the possibility of eternal life go undiscussed, we happily chew over the minutiae of misery. The syndrome recognizes no boundaries; in bath-house and seminar-room alike, the same ritual is repeated. With the inevitability of a tongue returning to probe a painful tooth, we come back and back and back again to our fears, sitting to talk them over with the eagerness of a hungry man before a full and steaming plate.

While he was still at university, and afraid to speak, Stephen Grace was taught to speak of why he was afraid. In fact not simply to talk about it, but to analyze and dissect his every nerve ending, looking for tiny terrors.

In this investigation, he had a teacher: Quaid.

It was an age of gurus; it was their season. In universities up and down England young men and women were looking east and west for people to follow like lambs; Steve Grace was just one of many. It was his bad luck that Quaid was the Messiah he found.

They'd met in the Student Common Room.

"The name's Quaid," said the man at Steve's elbow at the bar.

"Oh."

"You're —?"

"Steve Grace."

"Yes. You're in the Ethics class, right?"

"Right."

"I don't see you in any of the other Philosophy seminars or lectures."

"It's my extra subject for the year. I'm on the English Literature course. I just couldn't bear the idea of a year in the Old Norse classes."

"So you plumped for Ethics."

"Yes."

Quaid ordered a double brandy. He didn't look that well off, and a double brandy would have just about crippled Steve's finances for the next week. Quaid downed it quickly, and ordered another.

"What are you having?"

Steve was nursing half a pint of luke-warm lager, determined to make it last an hour.

"Nothing for me."

"Yes you will."

"I'm fine."

"Another brandy and a pint of lager for my friend."

Steve didn't resist Quaid's generosity. A pint and a half of lager in his unfed system would help no end in dulling the tedium of his oncoming seminars on ‘Charles Dickens as a Social Analyst'. He yawned just to think of it.

"Somebody ought to write a thesis on drinking as a social activity."

Quaid studied his brandy a moment, then downed it.

"Or as oblivion," he said.

Steve looked at the man. Perhaps five years older than Steve's twenty. The mixture of clothes he wore was confusing. Tattered running shoes, cords, a grey-white shirt that had seen better days: and over it a very expensive black leather jacket that hung badly on his tall, thin frame. The face was long and unremarkable; the eyes milky-blue, and so pale that the colour seemed to seep into the whites, leaving just the pin-pricks of his irises visible behind his heavy glasses. Lips full, like a Jagger, but pale, dry and un-sensual. Hair, a dirty blond.

Quaid, Steve decided, could have passed for a Dutch dope-pusher.

He wore no badges. They were the common currency of a student's obsessions, and Quaid looked naked without something to imply how he took his pleasures. Was he a gay, feminist, save-the-whale campaigner; or a fascist vegetarian? What was he into, for God's sake?

"You should have been doing Old Norse," said Quaid.

"Why?"

"They don't even bother to mark the papers on that course," said Quaid.

Steve hadn't heard about this. Quaid droned on.

"They just throw them all up into the air. Face up, an A. Face down, a B."

Oh, it was a joke. Quaid was being witty. Steve attempted a laugh, but Quaid's face remained unmoved by his own attempt at humour.

"You should be in Old Norse," he said again. "Who needs Bishop Berkeley anyhow. Or Plato. Or —"

"Or?"

"It's all shit."

"Yes."

"I've watched you, in the Philosophy Class —"

Steve began to wonder about Quaid.

"— You never take notes do you?"

"No."

"I thought you were either sublimely confident, or you simply couldn't care less."

"Neither. I'm just completely lost."

Quaid grunted, and pulled out a pack of cheap cigarettes. Again, that was not the done thing. You either smoked Gauloises, Camel or nothing at all.

"It's not true philosophy they teach you here," said Quaid, with unmistakable contempt.

"Oh?"

"We get spoon-fed a bit of Plato, or a bit of Bentham —no real analysis. It's got all the right markings of course. It looks like the beast: it even smells a bit like the beast to the uninitiated."

"What beast?"

"Philosophy. True Philosophy. It's a beast, Stephen. Don't you think?"

"I hadn't -"

"It's wild. It bites."

He grinned, suddenly vulpine. "Yes. It bites," he replied. Oh, that pleased him. Again, for luck: "Bites."

Stephen nodded. The metaphor was beyond him. "I think we should feel mauled by our subject." Quaid was warming to the whole subject of mutilation by education. "We should be frightened to juggle the ideas we should talk about."

"Why?"

"Because if we were philosophers we wouldn't be exchanging academic pleasantries. We wouldn't be talking semantics; using linguistic trickery to cover the real concerns."

"What would we be doing?"

Steve was beginning to feel like Quaid's straight man, except that Quaid wasn't in a joking mood. His face was set: his pinprick irises had closed down to tiny dots

"We should be walking close to the beast, Steve, don't you think? Reaching out to stroke it, pet it, milk it—"

"What... er... what is the beast?"

Quaid was clearly a little exasperated by the pragmatism of the enquiry.

"It's the subject of any worthwhile philosophy, Stephen. It's the things we fear, because we don't understand them. It's the dark behind the door."

Steve thought of a door. Thought of the dark. He began to see what Quaid was driving at in his labyrinthine fashion. Philosophy was a way to talk about fear.

"We should discuss what's intimate to our psyches," said Quaid. "If we don't....e risk..."

Quaid's loquaciousness deserted him suddenly.

"What?"

Quaid was staring at his empty brandy glass, seeming to will it to be full again.

"Want another?" said Steve, praying that the answer would be no.

"What do we risk?" Quaid repeated the question. "Well, I think if we don't go out and find the beast —"

Steve could see the punchline coming.

"- sooner or later the beast will come and find us."

There is no delight the equal of dread. As long as it's someone else's.

Casually, in the following week or two, Steve made some enquiries about the curious Mr Quaid.

Nobody knew his first name.

Nobody was certain of his age; but one of the secretaries thought he was over thirty, which came as a surprise.

His parents, Cheryl had heard him say, were dead. Killed, they thought.

That appeared to be the sum of human knowledge where Quaid was concerned.

"I owe you a drink," said Steve, touching Quaid on the shoulder.

He looked as though he'd been bitten.

"Brandy?"

"Thank you." Steve ordered the drinks. "Did I startle you?"

"I was thinking."

"No philosopher should be without one."

"One what?"

"Brain."

They fell to talking. Steve didn't know why he'd approached Quaid again. The man was ten years his senior and in a different intellectual league. He probably intimidated Steve, if he was to be honest about it. Quaid's relentless talk of beasts confused him. Yet he wanted more of the same: more metaphors: more of that humourless voice telling him how useless the tutors were, how weak the students.

In Quaid's world there were no certainties. He had no secular gurus and certainly no religion. He seemed incapable of viewing any system, whether it was political or philosophical, without cynicism.

Though he seldom laughed out loud, Steve knew there was a bitter humour in his vision of the world. People were lambs and sheep, all looking for shepherds. Of course these shepherds were fictions, in Quaid's opinion. All that existed, in the darkness outside the sheep-fold were the fears that fixed on the innocent mutton: waiting, patient as stone, for their moment.

Everything was to be doubted, but the fact that dread existed.

Quaid's intellectual arrogance was exhilarating. Steve soon came to love the iconoclastic ease with which he demolished belief after belief. Sometimes it was painful when Quaid formulated a water-tight argument against one of Steve's dogma. But after a few weeks, even the sound of the demolition seemed to excite. Quaid was clearing the undergrowth, felling the trees, razing the stubble. Steve felt free.

Nation, family, Church, law. All ash. All useless. All cheats, and chains and suffocation.

There was only dread.

"I fear, you fear, we fear," Quaid was fond of saying. "He, she or it fears. There's no conscious thing on the face of the world that doesn't know dread more intimately than its own heartbeat."

One of Quaid's favourite baiting-victims was another Philosophy and Eng. Lit. student, Cheryl Fromm. She would rise to his more outrageous remarks like fish to rain, and while the two of them took knives to each other's arguments Steve would sit back and watch the spectacle. Cheryl was, in Quaid's phrase, a pathological optimist.

"And you're full of shit," she'd say when the debate had warmed up a little. "So who cares if you're afraid of your own shadow? I'm not. I feel fine."

She certainly looked it. Cheryl Fromm was wet dream material, but too bright for anyone to try making a move on her.

"We all taste dread once in a while," Quaid would reply to her, and his milky eyes would study her face intently, watching for her reaction, trying, Steve knew, to find a flaw in her conviction.

"I don't."

"No fears? No nightmares?"

"No way. I've got a good family; don't have any skeletons in my closet. I don't even eat meat, so I don't feel bad when I drive past a slaughterhouse. I don't have any shit to put on show. Does that mean I'm not real?"

"It means," Quaid's eyes were snake-slits, "it means your confidence has something big to cover."

"Back to nightmares."

"Big nightmares."

"Be specific: define your terms."

"I can't tell you what you fear."

"Tell me what you fear then."

Quaid hesitated. "Finally," he said, "It's beyond analysis."

"Beyond analysis, my ass!"

That brought an involuntary smile to Steve's lips. Cheryl's ass was indeed beyond analysis. The only response was to kneel down and worship.

Quaid was back on his soap-box.

"What I fear is personal to me. It makes no sense in a larger context. The signs of my dread, the images my brain uses, if you like, to illustrate my fear, those signs are mild stuff by comparison with the real horror that's at the root of my personality."

"I've got images," said Steve. "Pictures from childhood that make me think of —" He stopped, regretting this confessional already.

"What?" said Cheryl. "You mean things to do with bad experiences? Falling off your bike, or something like that?"

"Perhaps," Steve said. "I find myself, sometimes, thinking of those pictures. Not deliberately, just when my concentration's idling. It's almost as though my mind went to them automatically."

Quaid gave a little grunt of satisfaction. "Precisely," he said.

"Freud writes on that," said Cheryl.

"What?"

"Freud," Cheryl repeated, this time making a performance of it, as though she were speaking to a child. "Sigmund Freud: you may have heard of him."

Quaid's lip curled with unrestrained contempt. "Mother fixations don't answer the problem. The real terrors in me, in all of us, are pre-personality. Dread's there before we have any notion of ourselves as individuals. The thumb-nail, curled up on itself in the womb, feels fear."

"You remember do you?" said Cheryl.

"Maybe," Quaid replied, deadly serious.

"The womb?"

Quaid gave a sort of half-smile. Steve thought the smile said: "I have knowledge you don't."

It was a weird, unpleasant smile; one Steve wanted to wash off his eyes.

"You're a liar," said Cheryl, getting up from her seat, and looking down her nose at Quaid.

"Perhaps I am," he said, suddenly the perfect gentleman.

After that the debates stopped.

No more talking about nightmares, no more debating the things that go bump in the night. Steve saw Quaid irregularly for the next month, and when he did Quaid was invariably in the company of Cheryl Fromm. Quaid was polite with her, even deferential. He no longer wore his leather jacket, because she hated the smell of dead animal matter. This sudden change in their relationship confounded Stephen; but he put it down to his primitive understanding of sexual matters. He wasn't a virgin, but women were still a mystery to him: contradictory and puzzling.

He was also jealous, though he wouldn't entirely admit that to himself. He resented the fact that the wet dream genius was taking up so much of Quaid's time.

There was another feeling; a curious sense he had that Quaid was courting Cheryl for his own strange reasons. Sex was not Quaid's motive, he felt sure. Nor was it respect for Cheryl's intelligence that made him so attentive. No, he was cornering her somehow; that was Steve's instinct. Cheryl Fromm was being rounded up for the kill.

Then, after a month, Quaid let a remark about Cheryl drop in conversation.

"She's a vegetarian," he said.

"Cheryl?"

"Of course, Cheryl."

"I know. She mentioned it before."

"Yes, but it isn't a fad with her. She's passionate about it. Can't even bear to look in a butcher's window. She won't touch meat, smell meat —"

"Oh." Steve was stumped. Where was this leading?

"Dread, Steve."

"Of meat?"

"The signs are different from person to person. She fears meat. She says she's so healthy, so balanced. Shit! I'll find —"

"Find what?"

"The fear, Steve."

"You're not going to...?" Steve didn't know how to voice his anxiety without sounding accusatory.

"Harm her?" said Quaid. "No, I'm not going to harm her in any way. Any damage done to her will be strictly self-inflicted."

Quaid was staring at him almost hypnotically. "It's about time we learnt to trust one another," Quaid went on. He leaned closer. "Between the two of us —"

"Listen, I don't think I want to hear."

"We have to touch the beast, Stephen."

"Damn the beast! I don't want to hear!"

Steve got up, as much to break the oppression of Quaid's stare as to finish the conversation.

"We're friends, Stephen."

"Yes..."

"Then respect that."

"What?"

"Silence. Not a word."

Steve nodded. That wasn't a difficult promise to keep. There was nobody he could tell his anxieties to without being laughed at.

Quaid looked satisfied. He hurried away, leaving Steve feeling as though he had unwillingly joined some secret society, for what purpose he couldn't begin to tell. Quaid had made a pact with him and it was unnerving.

For the next week he cut all his lectures and most of his seminars. Notes went uncopied, books unread, essays unwritten. On the two occasions he actually went into the university building he crept around like a cautious mouse, praying he wouldn't collide with Quaid.

He needn't have feared. The one occasion he did see Quaid's stooping shoulders across the quadrangle he was involved in a smiling exchange with Cheryl Fromm. She laughed, musically, her pleasure echoing off the walls of the History Department. The jealousy had left Steve altogether. He wouldn't have been paid to be so near to Quaid, so intimate with him.

The time he spent alone, away from the bustle of lectures and overfull corridors, gave Steve's mind time to idle. His thoughts returned, like tongue to tooth, like fingernail to scab, to his fears.

And so to his childhood.

At the age of six, Steve had been struck by a car. The injuries were not particularly bad, but a concussion left him partially deaf. It was a profoundly distressing experience for him; not understanding why he was suddenly cut off from the world. It was an inexplicable torment, and the child assumed it was eternal.

One moment his life had been real, full of shouts and laughter. The next he was cut off from it, and the external world became an aquarium, full of gaping fish with grotesque smiles. Worse still, there were times when he suffered what the doctors called tinnitus, a roaring or ringing sound in the ears. His head would fill with the most outlandish noises, whoops and whistlings, that played like sound-effects to the flailings of the outside world. At those times his stomach would churn, and a band of iron would be wrapped around his forehead, crushing his thoughts into fragments, dissociating head from hand, intention from practice. He would be swept away in a tide of panic, completely unable to make sense of the world while his head sang and rattled.

But at night came the worst terrors. He would wake, sometimes, in what had been (before the accident) the reassuring womb of his bedroom, to find the ringing had begun in his sleep.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

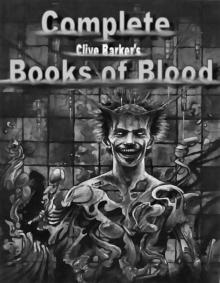

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

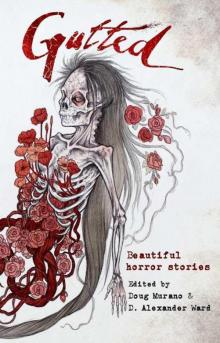

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

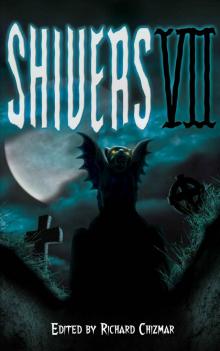

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

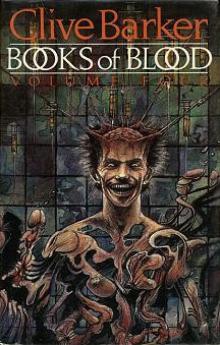

Books Of Blood Vol 4