- Home

- Clive Barker

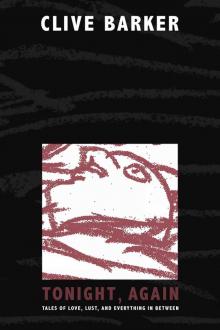

Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Read online

Tonight, Again: Tales of Love, Lust, and Everything in Between Copyright © 2015

by Clive Barker. All rights reserved.

Dust jacket illustration Copyright © 2015 by Brandon Mahlberg. All rights reserved.

Interior illustrations Copyright © 2015 by Clive Barker. All rights reserved.

Print interior design Copyright © 2015 by Desert Isle Design, LLC. All rights reserved.

Digital Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-695-3

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

subterraneanpress.com

For Ben Meares

Table of Contents

Tonight, Again —11

I Love You —13

Craw: a Fable —15

Afraid —41

Moved —47

I Imagine You —49

If the Pen is the Penis —51

Touch the Rod —53

Martha —55

Tit —67

The Freaks —69

Cruelty —71

Dollie —73

The Collection —81

What May Not Be Shown —85

Two Views from a Window —89

Men in the Aisles of Supermarkets —95

A Blessing —99

Unrequited — 105

Another Genesis —111

Inside Out (Wasteland) —115

I Have My Art —117

Aurora —119

Whistling in the Dark —121

The Common Flesh —123

Mr. Fred Coady Professes His

Undying Love for His Little Sylvia —125

The Phone Call —131

The Multitude —137

A Monster Lies in Wait —139

An Incident at the Nunnery —141

The Genius of Denny Dan —149

Tonight, Again

Tonight, again, he opens his heart, though it is more difficult every time he does so. The scar tissue is thick, and the flesh refuses to part easily. His body cavorts in the chair as he cuts at himself.

He avoids mirrors, though on occasion circumstances demand that he view himself. One of his lovers, a woman called Cassandra, said she believed he was a vampire. To prove her wrong he had her bring a mirror into the room.

“There!” he said, pointing to his reflection.

The sight was so shocking, however—his skin sallow, his body painfully thin—that he almost wished he were a vampire; as to be spared his own reflection.

And yet he never wants for lovers; never. Men and women alike press their attentions upon him. Some of them, wanting more of his company than he can provide, have attempted suicide. Some have succeeded. But what can he do? It’s as painful for him to be loved as it is for them to love him. To open his body to them, as he does, to let them kneel before him and lick his heart, as he does; this is agony. Though a surgeon he knew (one of the suicides, in fact) told him that his innards have no nerve-endings, and should not respond to the touch of a tongue, this is not his experience. He feels it. And after the lover has gone, and the wound begins to heal, he tells himself “enough, don’t do this anymore, it’s stupid.”

For a while—perhaps two days, perhaps three days—he refuses to see anyone. He draws the drapes. He sits in front of the television and heals. If the telephone rings, he doesn’t answer it. If somebody knocks on the door, he turns the volume down on the television, and waits in silence until they’ve gone.

But his resolve never lasts. After a time he gives in, and answers the phone or opens the door. He only has to hear the pain in the voice at the other end of the line, or see the need in the eyes of the person at the threshold, and he is lost.

Tonight, again, he opens his flesh and wonders if it will be the last time. Then the young man’s tongue licks his tender heart and for a wonderful moment he is glad to be alive.

I love you

And the noise of strife

Has never silenced what I feel.

I love you,

As a husband loves a wife,

As priests before the altar

Come to kneel.

I love you, and I cannot hope

For anything more sweet than this,

That at the end

Of my unfathomed life

You’re there to love me into death,

With one last tender kiss.

Craw: A Fable

At the northeast end of the orchard, close to the old stone wall which marked the perimeter of her father’s land, was Francesca’s tree. It had ceased to bear its annual bounty of purple plums three years ago, and were it not for his daughter’s pleas on its behalf, Papa Rueffert would doubtless had have one of his three sons chop it down. Indeed his foreman Arturo had warned him that the tree’s fruitlessness might be evidence of some disease it was carrying, and if left unchecked might well spread through the entire orchard.

“I’ll take the risk,” Rueffert had said. “My daughter loves that tree.”

“Daughters will be the death of me!” the foreman had snorted (he had six of his own). “They’re more trouble than they’re worth.”

Francesca could be a difficult girl, no doubt of that. She was willful, she was impertinent, and for a thirteen-year-old she was precociously interested in the matter of sex. Nor was she shy about voicing her curiosity. It was not uncommon for her to drop into conversation over dinner some question as to the anatomy of manliness which would have hushed a room full of medical students. Her mother— a quiet, God-fearing woman—would gently tell Francesca that such enquiries were not appropriate at the dinner table, but it did little good. At last, Mama Rueffert consulted Father Kronhausen, who came up to the house one night to talk with Francesca. He intended to put the fear of God into the child, and for a little while it seemed he had succeeded. For several weeks after their chat Francesca asked no questions; instead she took to reading a great deal. Her favourite place to retreat with her books was the branches of her plum tree. There she would sit through the sultry afternoons, reading the cheap romantic novelettes she’d found hidden at the bottom of her mother’s wardrobe.

She wasn’t alone at the far end of the orchard, however. As the August days went by, she sensed that there was somebody else who liked to linger around that corner of the orchard. It was not, she thought, a man. She was plenty old enough to know what a man’s gaze felt like. This was some other presence. But what?

After a few days of wondering, she formulated a plan. She took a small mirror down to the orchard with her, and hid it in the pages of a book. When she sensed the stranger’s gaze upon her, she lifted her book up and used the mirror to scan the area around the tree. At first she saw nothing. It wasn’t until she leaned back against the branch, and casually lifted the book above her head, that she caught sight of the voyeur. There at the base of the tree, lying low in the grass, was a creature the like of which she’d never seen before. It had some of the sinuous elegance of a cat, though it was ten times the size of domestic kitty. And its head had a distinctly reptilian cast; its eyes, which looked up at her with such lazy longing, grey-green in colour. What did it want of her, she wondered? Was there hunger in that stare? Did it want to suck the meat off her bones? She thought not. There was a kind of tenderness in the way it stared up at her. When she snapped her book closed, it fled away. By the time she had clambered down the tree there was no sign of it, except for a patch of flattened grass and daisies, where it had lain.

Amongst the men who tended Papa Rueffert’s orchard there was the foreman’s father, Arturo the Elder. He had become both addled and crippled in his dotage, but he always brightened up at the sight o

f Francesca. Today she found him in his hut, smoking a pipeful of sweet tobacco. After a little chat she asked him, in a casual manner, if he knew any stories about the orchard. Plenty, he replied. There’d been a duel fought there once upon a time; two fine officers fighting over a noble lady. Both had been killed, and the object of their affections had become a nun. Then there’d been a year—oh, long before Francesca was born—when a cloud of butterflies such as nobody had ever seen before had descended on the trees, and there’d been so many of them that when Papa Rueffert, against Old Arturo’s advice, had fired a gun to clear them away, the fluttering of their innumerable wings had brought down two-thirds of the crop before it was fully ripe. Francesca wasn’t interested in officers or butterflies, of course, but she listened nevertheless, hoping the old man would in time alight on the mystery she’d witnessed. Finally, after several more stories, he said:

“Then there’s the Craw, which comes to the orchard now and again.”

“The Craw?” said Francesca lightly. “What’s a Craw?”

“A beast,” Old Arturo said. “It comes from the wilderness on the other side of the stone wall. They say that it survived the flood, though Noah would make no room for it in the Ark.”

“Why was that?”

“Because the Craw had no wife, so it could not procreate.”

“Why isn’t it dead by now? The flood was years ago.”

Arturo the Elder drew on his pipe, as he thought on this. “Some things live longer than others,” he replied at last. “And then, maybe having no wife was good for its constitution. I know many a strong man undone by marriage.”

Francesca giggled. Old Arturo was pleased. He leaned close to the girl. “My wife ran away with a mountebank just after Little Arturo came along. That’s why I’m still here. She would have killed me with nagging by now.”

“This Craw…”

“It’s just a story.”

“But I still want to know: if I ever met it, would it hurt me?”

“Maybe it would, maybe it wouldn’t. Beasts are unpredictable.”

So I have to be careful, Francesca thought. I have to plan.

She was good at planning. That was something she got from her mother, who scarcely strayed out of the house without a plan.

Two days passed, and Francesca did not go down to her plum tree. On the third day, however, she went very early in the morning, before the house was up, and put her plan into action. It was strange to be in the orchard at such an early hour; beads of dew on every blade and petal, her skin prickling with the cold.

The threads of the spider’s webs that hung amongst the trees were not as fine as the line between fear and anticipation that morning. She knew that she was taking a terrible risk: that the Craw was from the wilderness beyond the stone wall, and had an uncivilized heart. But she was ready to dare whatever harm it might do, to have her curiosity satisfied.

Just as the Rueffert household was waking up—her brothers yelling and fighting as they did every morning—she slipped back into the house, and up the back stairs to her bedroom, where she pretended to be woken when her mother came knocking on the door.

The morning hours passed at a crawl. Her tutor came, and instructed her in a little French history and a little Latin grammar. Several times her attention strayed to the window, where the fruit-laden branch of a tree brushed the glass when the breeze caught it. Perhaps, she found herself thinking, this would be the last time she would ever listen to the dreary drone of her tutor’s voice. Perhaps tomorrow she’d be dead—torn limb from limb by the bestial Craw; or swallowed whole; or snatched away as women often were in the novelettes her mother read: taken by bandits or white-slavers and never seen again.

“What are you thinking about?” her tutor demanded to know. “It certainly isn’t Latin.”

“No,” she said, with a beguiling plainness. “It isn’t.”

At noon, the tutor departed. Francesca had lunch at the kitchen table, with her brothers. They were in a particularly raucous mood today, but their din didn’t bother her. She just ate to get her strength up for the afternoon, and then left them to squabble. She went upstairs to get the book she was reading, which was Gulliver’s Travels, and went down through the orchard to her tree. Her heart was thumping so hard she thought she might burst, her head filled with questions. What if the Craw had been hiding behind the wall when she’d come to the tree at dawn? What if it knew that she was up to something, and decided to pounce on her before she even reached her sanctuary? With every step she took she half-expected the creature to rush out of hiding and rake her with its claws, undoing her.

But nothing happened. The orchard was as quiet and calm as ever. The wind was still gusty enough to make the smaller branches sway, but not so strong that it carried off the birds which sat in those branches, singing out their summer songs.

Francesca put the book between her teeth, and climbed the tree. Then she settled herself down in the cradle of the branches, turned to her place in the book, and pretended to show some interest in the fourth voyage of Lemuel Gulliver. Five minutes passed; then another five, and then another five, and Francesca began to wonder if today the Craw had decided not to come.

She was just about to close her book, and climb back down the tree, when she heard a subtle rustling in the grass. Moments later she felt the familiar gaze upon her. The Craw had come after all. She had not brought her mirror to spy on it this time. She was much more direct. She simply turned over in her bower, so that she had her belly to the branch, and looked down at the ground. The Craw flattened itself against the grass, and lay absolutely still, thinking it might avoid being seen. It was indeed cannily camouflaged; on its back was a pattern that resembled the dapple of light and leaf-shadow. But Francesca saw it clearly enough: its long, lean body, its flat wide head, its yearning eyes.

She let one leg drop a little way off the branch, and let the sandal slide from her long pale foot, so that she was holding on to it with just one toe. She thought she heard the Craw sigh. She let the sandal rock gently back and forth, and then she let it slip off completely. It fell to the grass. The beast didn’t move. It clearly thought that its victim had so far not seen it. Several seconds passed. Perhaps a minute. Then Francesca laid her head down on the branches and pretended to go to sleep. She was good at this; closing her eyes until they seemed to be sealed shut, while in fact she was watching between the bars of her lashes. Another minute passed, and finally the Craw seemed to decide that it was safe to move. Keeping its head low and its belly tight to the ground, it slunk towards the tree. When it reached Francesca’s sandal it stopped, and sniffed. Not one sniff but a dozen or more, as though it was inhaling every nuance of her scent. A little tremor of excitement ran through Francesca. In her pretended sleep she pressed herself against the curve of the thick branch on which she lay, and made a little noise of contentment. This plainly reassured the Craw, for it immediately became more adventurous, lifting its head up off the ground towards Francesca’s dangling foot. She thought of her toes like five worms cast in a river by a fisherman; pink and appetizing. If the Craw snapped at them now, she’d be lost. He’d pull her down off her perch and into his mouth, which was, she could see, grotesquely large. It was all she could do not to let out a yell, and clamber up in to the highest branch of the plum tree, ’til her brothers came running to save her. But she kept her fear under control. She simply waited, while the Craw lifted its head closer, inch by tentative inch.

It sniffed her foot, as it had sniffed the sandal. She felt its hot breath on her sole. It tickled. Still pretending to be asleep, she gently drew her leg back up to the safety of her bower. The Craw, like the lured fish it had become, followed, stretching its neck as far as it would go and then putting its forepaws up against the trunk of the tree so as to get even closer to her. There was a flicker of crimson in its golden eyes, she saw, and its breath had quickened. Its nose was no longer inhaling the scents of her foot, but had moved on, past her ankle, and up the len

gth of her shin. She drew her leg up towards her body, making the beast clamber up a little higher in pursuit of her. She had no fear of it now. Well, a little perhaps, but just enough to offer a certain piquancy to her pleasure.

The tree shook a little as the claws of its hind legs dug into the trunk. Its nose had lingered behind her knee, taking its time to savour the sweat in the creases there. But it did not investigate her thigh. Instead it went directly to the place between her legs. Her little dress had ridden up against the branch, and her underwear was pulled tight in the cleft of her body. It offered little protection against the creature’s enquiries.

Another flurry of tremors shook her, beginning at the back of her neck and running down her spine to her fundament. The Craw let out a low moan. She pretended that the sound had half-stirred her from her sleep: made a moan of her own, and moved up the branch a little, as though looking for a more comfortable cradle. The Craw froze, but only for a second or two. Then it climbed up the tree a little further, coming after her. Just a few more inches, she knew, and she had it. All she had to do was lie still and let it come to her. That wasn’t so hard. There was a part of her that wanted the beast’s nose hard against her little slit, snuffling around like a pig. It would have plenty to sniff at down there, she knew; sometimes she was amazed at how powerful the smell of her own body could be.

She moved on up the branch; it came after her in a heartbeat. Another inch or two and it’d be perfectly positioned. It pushed against her, the moisture around its snout soaking her underwear. Very slowly she reached out along the branch to the rope that was hanging up there, concealed by the foliage. Its eyes had fluttered closed, it was in such bliss. She caught hold of the rope and pulled. The branches overhead shook as the weighted net she’d hidden up there dropped down. As it descended she scrambled on up the branch in case the Craw attacked her, but she needn’t have concerned herself. The beast was too panicked to fight back, thrashing in the net but only managing to get itself more and more entangled. She was quick, then. She started to pass lengths of rope through the mesh and around the branch, and tied them off, trapping the beast. The Craw seemed to understand very quickly that it had been outwitted, because it gave up its struggles and instead began to issue a series of plaintive moans. As it did so it used what little room it had in the trap to half-roll itself over, showing the paleness of its underbelly to Francesca.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4