- Home

- Clive Barker

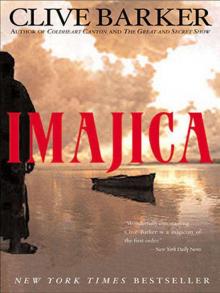

Imajica: Annotated Edition

Imajica: Annotated Edition Read online

The Journey of Three Lifetimes

THERE HAS NEVER BEEN a book like Imajica. Transforming every expectation of fantasy fiction with its heady mingling of radical sexuality and spiritual anarchy, it has carried its millions of readers into regions of passion and philosophy that few books have even attempted to map. It’s an epic in every way; vast in conception, obsessively detailed in execution, and apocalyptic in its resolution. A book of erotic mysteries and perverse violence. A book of ancient, mythological landscapes and even more ancient magic.

Most of all, it’s a book of extraordinary characters. At its heart lies the great sensualist and master art forger, Gentle, whose life of excess comes unravelled when he encounters two other unforgettable individuals: Judith Odell, whose power to influence the destinies of the men besotted by her is vaster than she knows, and Pie ‘oh’ pah, an alien assassin who comes from a dimension most of us don’t even know exists.

That dimension—or Dominion, as it is known—is one of five in the great system called Imajica. They are worlds which are in many ways utterly unlike our own, but which are ruled, peopled, and haunted by species whose lives are intricately connected with us. As Gentle, Judith, and Pie ‘oh’ pah travel the Imajica—from the darkness of its infernal regions into its visionary places—they uncover a trail of Dominion-spanning crimes and intimate betrayals that will lead them to a revelation so startling it will change the way you look at reality forever.

Contents

HarperCollins e-book exclusive:

Afterward(s): Clive Barker on Imajica

Illustrations

Book 1

The Fifth Dominion

One It was the pivotal teaching of Pluthero Quexos. . .

Two Do this for the women of the world. . .

Three At dusk the clouds over Manhattan. . .

Four Eleven days after he had taken . . .

Five Two days after the predawn call . . .

Six Chant’s body was discovered the . . .

Seven Gentle called Klein from the . . .

Eight When he got back to the . . .

Nine Oscar Esmond Godolphin always . . .

Ten The afternoon of the day following . . .

Eleven Though the journey from Godolphin’s . . .

Twelve Taylor Briggs had once told Judith . . .

Thirteen She had seen two people where . . .

Fourteen While it was to prove dif .cult for . . .

Fifteen In her rage at his conspiracies Jude . . .

Sixteen Since the meeting at which the subject . . .

Seventeen Towards midnight,the traffic outside . . .

Eighteen Until the rise of Yzordderrex,a rise . . .

Nineteen Though Jude had made an oath,in all . . .

Twenty Gentle and Pie were six days on the . . .

Twenty-one The Retreat at the Godolphin estate . . .

Twenty-two The days following Pie and Gentle’s . . .

Twenty-three Gentle dreamed that the wind . . .

Twenty-four England saw an early spring . . .

Twenty-five Twenty-two days after emerging from . . .

Twenty-six Gentle woke to the sound of a prayer.

Twenty-seven If pressed,Jude could have named . . .

Twenty-eight Gentle had forgotten his short exchange . . .

Twenty-nine The territory that lay between . . .

Thirty When Dowd brought Judith back . . .

Thirty-one Five miles up the mountainside from . . .

Thirty-two With the long Yzordderrexian twilight . . .

Thirty-three Gentle did as he’d promised . . .

Thirty-four Every trace of the joy that . . .

Thirty-five Demanding directions as he went,. . .

Thirty-six Gentle’s thoughts had not often . . .

Book 2

The Reconciliation

One Like the theater districts of so . . .

Two In any other place but this, Gentle . . .

Three The Comet’s ascent into the heavens . . .

Four Like galleons turned to the desert . . .

Five When he returned inside, it was . . .

Six Jude was stirred from the torpor . . .

Seven One hundred and fifty-seven days . . .

Eight Though the bed Gentle had . . .

Nine Although Jude had not slept well . . .

Ten Though Jude’s memory of the night . . .

Eleven “And who the fuck are you?”

Twelve Despite Oscar’s prediction,the Tabula . . .

Thirteen Clem’s duties were done for . . .

Fourteen Even though Gentle had known . . .

Fifteen The sun that met Gentle in the . . .

Sixteen There was surely no more haunted . . .

Seventeen After all that Monday had said . . .

Eighteen The mantle of night was falling . . .

Nineteen The law-defying waters were . . .

Twenty In his last letter to his son,written . . .

Twenty-one Whatever debates and quarrels went . . .

Twenty-two Gentle wasn’t the only occupant . . .

Twenty-three f coming to the moment of . . .

Twenty-four Gentle’s spirit went from the . . .

Twenty-five For the living occupants of . . .

Twenty-six In the Fifth,winter came:not . . .

Appendix

About the Author

Also by Clive Barker

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

ILLUSTRATIONS

CELESTINE

CONCUPISCENTIA

CRADLE OF CHZERCEMIT

GEK-A-GEK

GLYPH

IN OVO

LITTLE EASE

NULLIANAC

OETHACS

THE RETREAT

THE RIGHTEOUS

SISTERS OF THE DELTA

THE UNBEHELD

VANAEPH

YZORDDERREX

ZARZI

Afterword(s): Clive Barker on Imajica

Editor’s note: The reader who wishes to navigate all of Imajica’s twists and turns unaided by a map is advised to read the novel itself prior to reading the material that follows.

I wanted to create my own legends

Imajica took fourteen months from the time I first put pen to paper till the day I turned it in. That was writing seven days a week, fourteen hours a day. Towards the end it was sixteen hours a day. But it was a book which obsessed me, right from the very beginning. I don’t quite know yet why that is. Part of it was the fact that the sheer scale of it required total immersion if I was going to pull it off. If I hadn’t gotten it right — and I hope I’ve gotten it at least part right — then I would have looked like a real fool, because here I am dealing with Christ and God and magic and all that stuff.

And when, halfway through the book, the audience realises that Hapexamendios is the same God that people are worshipping when they go to Sunday Mass, the danger was that the audience would say, “Oh, give me a break. I’ll accept the idea of an invented god, but now you’re asking me to believe that this god is Jehovah, this god is Yahweh, this god is the God whom people worship in the Western world” — and that’s a very different thing from one of the gods of a [Stephen] Donaldson novel.

There is a danger of alienating [some readers]. I am sure there are going to be people who will say, “Sorry, this is too long.” But I also think there’s an audience that says, “Give me everything. Tell me everything you can tell me.”

Over the last forty years there’s been a huge and consistent audience for Lord of the Rings and there’s certainly a huge audience for the Dune books. I wanted to create my

own legends; I wanted to create something that my readership could enter into and invest their time and emotion in and feel deeply about over a period of many days, or even weeks, and that would stay with them as a world they could enter and re-experience if they wanted.

From “Boundless Imajination” by W.C. Stroby, published in Fangoria, January 1992.

Knocking down the whole damn wall

The worlds which open up in Imajica, just in terms of their physical scale, not to mention their metaphysical scale, are so much larger than I would have dared attempt even a couple of years ago. My readers . . . are very glad that they have more than the shock tactics to engage them through an 850-page book. And remember, the horror, the darkness, has never gone. Imajica has still got some very dark passages in it. So have The Great and Secret Show and Weaveworld. What’s been added is this, hopefully, transcendental level.

What’s also been added is a sense of thoroughly created worlds — I mean worlds with names, tribes, flora and fauna, religions, cults, and so on. I did hint at dimensions hidden in secret places in the horror fiction, obviously, and a lot of it contains the sense that if you open the wrong door you’re going to find yourself lost in another world. The way I’m doing it now, it’s not just opening the door but knocking down the whole damn wall and saying, “Here it all is.” The readership, I think, is very excited by that prospect.

In order to get through a big novel like Imajica, both as a reader and as a writer, you need mystery — and you can’t have one mystery, you need to have many. There’s a pulling away of the veils constantly. What I’ve tried to do to the reader is say, “There isn’t the solid moral clarity of Lord of the Rings.” I do the reverse of that. Imajica’s characters are human beings like you and I who, of course, discover a larger purpose for themselves. But in discovering a larger purpose, rather than becoming more themselves — like the hobbits out there in the wilderness becoming more hobbity — my characters skin themselves. The lives they have fall away.

From “A Strange Kind of Believer” by Stan Nicholls, published in Million, February 1993.

An act of massive consequence

Imajica started with my thinking about the images which appear in the great paintings of Christian mythology. Whether or not they’re true, they seemed to me to be potent, powerful, and important cyphers of image and meaning. So I considered writing a book which would be a fantasy, but which would also be about God, about belief, about a man who discovers that all his life he has been preparing for an act of massive consequence but didn’t realise it.

In Imajica we have someone who is like the half-brother of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, but who is completely unaware of the fact. Not only this, but he also had a massive past responsibility which he has screwed up and forgotten.

A lot of this came from the feeling that there is so much more in us than we completely comprehend, that our day-to-day lives with their petty annoyances perhaps shouldn’t distract us from a grander and deeper perception of ourselves.

From “Barker USA” by David Howe, published in Starburst Yearbook 1991/92.

Imajica stands to the life of Christ

As Weaveworld stood to the story of the Garden of Eden, this stands to the life of Christ. It’s about what magic is really for, and it’s not for bringing rabbits out of hats.

From “The Meaning of Magic” by Mark Salisbury, published in Fear, October 1990.

All kinds of villainies against women

Hapexamendios, the villain of Imajica, is the . . . . personification of the joyless, loveless, corrupt thing which has over eons created his own city of his own flesh. It happens to be, when you look at it, an extraordinary city, a glorious city. But when you look really closely at it, you see that it is a completely empty city. There’s nobody there, there’s no love there, there’s no joy there; there’s no compassion there because there are no people there. It’s just a self-serving system of self-glorification. Hapexamendios is, in a curious way, its prisoner.

He’s finally dispatched simply because he wanted to destroy Goddesses. So the second part of the problem of the patriarchal God is that he’s been so successful, that he’s basically beaten out all the women, beaten out the matriarchs, and beaten out the Goddesses. I’m not saying that every Goddess out there was a good Goddess, because clearly there were some real villains among them. I’m sure really terrible things were done in the name of a Goddess — human sacrifice, castration, and all kinds of other things.

I do believe that a certain balance is healthy. And the balancing of images of divinity in both sexes is what’s important here. The balancing of the Goddesses against the God, the image of procreation as against the image of the fertiliser. Enup, the sky Goddess of Egyptian mythology, overreaching the God who lies below. A wonderful, frightening image of sexual compatibility and the geographical ompatibility of nature, of light and dark. What we’ve got in our system is one but not the other. We’ve got this incredibly one-sided vision of what the divine is.

What Imajica does is create a mythology in which we go about trying to understand why Hapexamendios has done this. What terror it is in men that makes them control and engage in all kinds of villainies against women. What a mingling of desire and envy will do. You look at most of the males in Imajica, they have one or the other where women are concerned, and in some cases they have both. So that is where that mythology is based.

From “Confessions” by Stephen Dressler and Cheryl Bentzen, published in Lost Souls, June 1995.

On Imajica becoming a movie

I think it’s impossible. In fact, I hope it’s impossible! I believe strongly that there are experiences which are best left on the page. An example: though I enjoyed Patrick Stewart recently playing Captain Ahab, nothing will ever convince me that the poetic density and metaphorical richness of Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick has a cinematic equivalent. Somehow, what is a literary vision of the page simply becomes a big ol’ whale story on the screen. I fear the same thing would happen with Imajica — that once the language which is used to describe this spiritual journey is removed, much of its power will be diminished.

From People Online, July 30 1998.

On Imajica being reality

Yes, in a strange way I do believe it’s possible. I don’t believe that our consciousness has fully grasped the complexity of reality, or, perhaps I should say, realities, in which we live. Our imaginations seem to offer us glimpses of other possibilities, other states of beings, other dimensions. I believe we will one day access those dimensions.

From People Online, July 30 1998.

The foreword to the 1995 two-volume edition

Back and back we go, searching for reasons; scrutinizing the past in the hope that we’ll turn up some fragment of an explanation to help us better understand ourselves and our condition.

For the psychologist, this quest is perhaps at root a pursuit of primal pain. For the physicist, a sniffing after evidence of the First Cause. For the theologian, of course, a hunt for God’s fingermarks on Creation.

And for a storyteller — particularly for a fabulist, a writer of fantastiques like myself — it may very well be a search for all three, motivated by the vague suspicion that they are inextricably linked.

Imajica was an attempt to weave these quests into a single narrative, folding my dilettante’s grasp of this trio of disciplines — psychology, physics, and theology — into an interdimensional adventure. The resulting novel sprawls, no doubt of that. The book is simply too cumbersome and too diverse in its concerns for the tastes of some. For others, however, Imajica’s absurd ambition is part of its appeal. These readers forgive the inelegance of the novel’s structure and allow that while it undoubtedly has its rocky roads and its cul-de-sacs, all in all the journey is worth the shoe leather.

For my publishers, however, a more practical problem became apparent when the book was prepared for its paperback edition. If the volume was not to be so thick that it would drop off a bookstore s

helf, then the type had to be reduced to a size that several people, myself included, thought less than ideal. When I received my author’s copies I was put in mind of a pocket-sized Bible my grandmother gave me for my eighth birthday, the words set so densely that the verses swam before my then-healthy eyes. It was not — I will admit — an entirely unpleasant association, given that the roots of Imajica’s strange blossom lay in the poetry of Ezekiel, Matthew, and Revelation. But I was well aware, as were my editors, that the book was not as reader-friendly as we all wished it was.

From those early misgivings springs this new, two-volume edition. Let me admit, in all honesty, that the book was not conceived to be thus divided. The place we have elected to split the story has no particular significance. It is simply halfway through the text, or thereabouts: a spot where you can put down one volume and — if the story has worked its magic — pick up the next. Other than the larger type, and the addition of these words of explanation, the novel itself remains unaltered.

Personally, I’ve never much cared about the details of one edition over another. While it’s very pleasurable to turn the pages of a beautifully bound book, immaculately printed on acid-free paper, the words are what count. The first copy of Poe’s short stories I ever read was a cheap, gaudily covered paperback; my first Moby-Dick the same. A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Duchess of Malfi were first encountered in dog-eared school editions. It mattered not at all that these enchantments were printed on coarse, stained paper. Their potency was undimmed. I hope the same will proved true for the tale you now hold: that the form it comes in is finally irrelevant.

With that matter addressed, might I delay you a little longer with a few thoughts about the story itself? At signings and conventions I am repeatedly asked a number of questions about the book, and this seems as good a place as any to briefly answer them.

Firstly, the question of pronunciation. Imajica is full of invented names and terms, some of which are puzzlers: Yzorddorex, Patashoqua, Hapexamendios, and so forth. There is no absolute hard and fast rule as to how these should trip, or stumble, off the tongue. After all, I come from a very small country where you can hike over a modest range of hills and find that the people you encounter on the far side use language in a completely different way to those whose company you left minutes before. There is no right or wrong in this. Language isn’t a fascist regime. It’s protean, and effortlessly defies all attempts to regulate or confine it. While it’s true that I have my own pronunciations of the words I’ve turned in the book, even those undergo modifications when — as has happened several times — people I meet offer more interesting variations. A book belongs at least as much to its readers as to its author, so please find the way the words sound most inviting to you and take pleasure in them.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4