- Home

- Clive Barker

Books of Blood Vol 2 Page 13

Books of Blood Vol 2 Read online

Page 13

He had been carried inside and was lying on an uncomfortable sofa, a woman's face, that of Eleanor Kooker, staring down at him. She beamed as he came round.

"The man'll survive," she said, her voice like cabbage going through a grater.

She leaned further forward.

"You seen the thing, did you?"

Davidson nodded.

"Better give us the low-down."

A glass was thrust into his hand and Eleanor filled it generously with whisky.

"Drink," she demanded, 'then tell us what you got to tell —"

He downed the whisky in two, and the glass was immediately refilled. He drank the second glass more slowly, and began to feel better.

The room was filled with people: it was as though all of Welcome was pressing into the Kooker front parlour. Quite an audience: but then it was quite a tale. Loosened by the whisky, he began to tell it as best he could, without embellishment, just letting the words come. In return Eleanor described the circumstances of Sheriff Packard's "accident" with the body of the car-wrecker. Packard was in the room, looking the worse for consoling whiskies and pain killers, his mutilated hand bound up so well it looked more like a club than a limb.

"It's not the only devil out there," said Packard when the stories were out.

"So's you say," said Eleanor, her quick eyes less than convinced.

"My Papa said so," Packard returned, staring down at his bandaged hand. "And I believe it, sure as Hell I believe it."

"Then we'd best do something about it."

"Like what?" posed a sour looking individual leaning against the mantelpiece. "What's to be done about the likes of a thing that eats automobiles?"

Eleanor straightened up and delivered a well-aimed sneer at the questioner.

"Well let's have the benefit of your wisdom, Lou," she said. "What do you think we should do?"

"I think we should lie low and let ‘em pass."

"I'm no ostrich," said Eleanor, "but if you want to go bury your head, I'll lend you a spade, Lou. I'll even dig you the hole."

General laughter. The cynic, discomforted, fell silent and picked at his nails.

"We can't sit here and let them come running through," said Packard's deputy, between blowing bubbles with his gum.

"They were going towards the mountains," Davidson said. "Away from Welcome."

"So what's to stop them changing their goddam minds?" Eleanor countered. "Well?"

No answer. A few nods, a few head shakings. "Jebediah," she said, "you're deputy — what do you think about this?"

The young man with the badge and the gum flushed a little, and plucked at his thin moustache. He obviously hadn't a clue.

"I see the picture," the woman snapped back before he could answer. "Clear as a bell. You're all too shit scared to go poking them divils out of their holes, that it?"

Murmurs of self-justification around the room, more head-shaking.

"You're just planning to sit yourselves down and let the women folk be devoured."

A good word: devoured. So much more emotive than eaten. Eleanor paused for effect. Then she said darkly: "Or worse."

Worse than devoured? Pity sakes, what was worse than devoured?

"You're not going to be touched by no divils," said Packard, getting up from his seat with some difficulty. He swayed on his feet as he addressed the room.

"We're going to have them shit-eaters and lynch ‘em." This rousing battle-cry left the males in the room unroused; the sheriff was low on credibility since his encounter in Main Street.

"Discretion's the better part of valour," Davidson murmured under his breath.

"That's so much horse-shit," said Eleanor.

Davidson shrugged, and finished off the whisky in his glass. It was not refilled. He reflected ruefully that he should be thankful he was still alive. But his work-schedule was in ruins. He had to get to a telephone and hire a car; if necessary have someone drive out to pick him up. The "divils", whatever they were, were not his problem. Perhaps he'd be interested to read a few column-inches on the subject in Newsweek, when he was back East and relaxing with Barbara; but now all he wanted to do was finish his business in Arizona and get home as soon as possible.

Packard, however, had other ideas.

"You're a witness," he said, pointing at Davidson, "and as Sheriff of this community I order you to stay in Welcome until you've answered to my satisfaction all inquiries I have to put to you."

The formal language sounded odd from his slobbish mouth.

"I've got business —" Davidson began.

"Then you just send a cable and cancel that business, Mr fancy-Davidson."

The man was scoring points off him, Davidson knew, bolstering his shattered reputation by taking pot-shots at the Easterner. Still, Packard was the law: there was nothing to be done about it. He nodded his assent with as much good grace as he could muster. There'd be time to lodge a formal complaint against this hick-town Mussolini when he was home, safe and sound. For now, better to send a cable, and let business go hang.

"So what's the plan?" Eleanor demanded of Packard.

The Sheriff puffed out his booze-brightened cheeks.

"We deal with the divils," he said.

"How?"

"Guns, woman."

"You'll need more than guns, if they're as big as he says they are —"

"They are —" said Davidson, "believe me, they are."

Packard sneered.

"We'll take the whole fucking arsenal," he said jerking his remaining thumb at Jebediah. "Go break out the heavy-duty weapons, boy. Anti-tank stuff. Bazookas."

General amazement.

"You got bazookas?" said Lou, the mantelpiece cynic.

Packard managed a leering smile.

"Military stuff," he said, "left over from the Big One." Davidson sighed inwardly. The man was a psychotic, with his own little arsenal of out-of-date weapons, which were probably more lethal to the user than to the victim. They were all going to die. God help him, they were all going to die.

"You may have lost your fingers," said Eleanor Kooker, delighted by this show of bravado, "but you're the only man in this room, Josh Packard."

Packard beamed and rubbed his crotch absent mindedly. Davidson couldn't take the atmosphere of hand-me-down machismo in the room any longer.

"Look," he piped up, "I've told you all I know. Why don't I just let you folks get on with it."

"You ain't leaving," said Packard, "if that's what you're rooting after."

"I'm just saying —"

"We know what you're saying son, and I ain't listening. If I see you hitch up your britches to leave I'll string you up by your balls. If you've got any."

The bastard would try it too, thought Davidson, even if he only had one hand to do it with. Just go with the flow, he told himself, trying to stop his lip curling. If Packard went out to find the monsters and his damn bazooka backfired, that was his business. Let it be.

"There's a whole tribe of them," Lou was quietly pointing out. "According to this man. So how do we take out so many of them?"

"Strategy," said Packard.

"We don't know their positions."

"Surveillance," replied Packard.

"They could really fuck us up Sheriff," Jebediah observed, picking a collapsed gum-bubble from his moustache.

"This is our territory," said Eleanor. "We got it: we keep it."

Jebediah nodded.

"Yes, ma," he said.

"Suppose they just disappeared? Suppose we can't find them no more?" Lou was arguing. "Couldn't we just let ‘em go to ground?"

"Sure," said Packard. "And then we're left waiting around for them to come out again and devour the women folk."

"Maybe they mean no harm —" Lou replied.

Packard's reply was to raise his bandaged hand.

"They done me harm."

That was incontestable.

Packard continued, his voice hoarse with feeling.

"Shit, I want them come-bags so bad I'm going out there with or without help. But we've got to out-think them, out manoeuvre them, so we don't get anybody hurt."

The man talks some sense, thought Davidson. Indeed, the whole room seemed impressed. Murmurs of approval all round; even from the mantelpiece.

Packard rounded on the deputy again.

"You get your ass moving, son. I want you to call up that bastard Crumb out of Caution and get his boys down here with every goddam gun and grenade they've got. And if he asks what for you tell him Sheriff Packard's declaring a State of Emergency, and I'm requisitioning every asshole weapon in fifty miles, and the man on the other end of it. Move it, son."

Now the room was positively glowing with admiration, and Packard knew it.

"We'll blow the fuckers apart," he said.

For a moment the rhetoric seemed to work its magic on Davidson, and he half-believed it might be possible; then he remembered the details of the procession, tails, teeth and all, and his bravado sank without trace.

They came up to the house so quietly, not intending to creep, just so gentle with their tread nobody heard them.

Inside, Eugene's anger had subsided. He was sitting with his legs up on the table, an empty bottle of whisky in front of him. The silence in the room was so heavy it suffocated.

Aaron, his face puffed up with his father's blows, was sitting beside the window. He didn't need to look up to see them coming across the sand towards the house, their approach sounded in his veins. His bruised face wanted to light up with a smile of welcome, but he repressed the instinct and simply waited, slumped in beaten resignation, until they were almost upon the house. Only when their massive bodies blocked out the sunlight through the window did he stand up. The boy's movement woke Eugene from his trance.

"What is it, boy?"

The child had backed off from the window, and was standing in the middle of the room, sobbing quietly with anticipation. His tiny hands were spread like sun-rays, his fingers jittering and twitching in his excitement.

"What's wrong with the window, boy?"

Aaron heard one of his true father's voices eclipse Eugene's mumblings. Like a dog eager to greet his master after a long separation, the boy ran to the door and tried to claw it open. It was locked and bolted.

"What's that noise, boy?"

Eugene pushed his son aside and fumbled with the key in the lock, while Aaron's father called to his child through the door. His voice sounded like a rush of water, counter pointed by soft, piping sighs. It was an eager voice, a loving voice.

All at once, Eugene seemed to understand. He took hold of the boy's hair and hauled him away from the door.

Aaron squealed with pain.

"Papa!" he yelled.

Eugene took the cry as addressed to himself, but Aaron's true father also heard the boy's voice. His answering call was threaded with piercing notes of concern.

Outside the house Lucy had heard the exchange of voices. She came out of the protection of her shack, knowing what she'd see against that sheening sky, but no less dizzied by the monumental creatures that had gathered on every side of the house. An anguish went through her, remembering the lost joys of that day six years previous. They were all there, the unforgettable creatures, an incredible selection of forms—Pyramidal heads on rose coloured, classically proportioned torsos, that umbrellaed into shifting skirts of lace flesh. A headless silver beauty whose six mother of pearl arms sprouted in a circle from around its purring, pulsating mouth. A creature like a ripple on a fast-running stream, constant but moving, giving out a sweet and even tone. Creatures too fantastic to be real, too real to be disbelieved; angels of the hearth and threshold. One had a head, moving back and forth on a gossamer neck, like some preposterous weather-vane, blue as the early night sky and shot with a dozen eyes like so many suns. Another father, with a body like a fan, opening and closing in his excitement, his orange flesh flushing deeper as the boy's voice was heard again.

"Papa!"

At the door of the house stood the creature Lucy remembered with greatest affection; the one who had first touched her, first soothed her fears, first entered her, infinitely gentle. It was perhaps twenty feet tall when standing at its full height. Now it was bowed towards the door, its mighty, hairless head, like that of a bird painted by a schizophrenic, bent close to the house as it spoke to the child. It was naked, and its broad, dark back sweated as it crouched.

Inside the house, Eugene drew the boy close to him, as a shield.

"What do you know, boy?"

"Papa?"

"I said what do you know?"

"Papa!"

Jubilation was in Aaron's voice. The waiting was over.

The front of the house was smashed inwards. A limb like a flesh hook curled under the lintel and hauled the door from its hinges. Bricks flew up and showered down again; wood-splinters and dust filled the air. Where there had once been safe darkness, cataracts of sunlight now poured onto the dwarfed human figures in the ruins.

Eugene peered up through the veil of dust. The roof was being peeled back by giant hands, and there was sky where there had been beams. Towering on every side he saw the limbs, bodies and faces of impossible beasts. They were teasing the remaining walls down, destroying his house as casually as he would break a bottle. He let the boy slip from his grasp without realizing what he'd done.

Aaron ran towards the creature on the threshold.

"Papa!"

It scooped him up like a father meeting a child out of school, and its head was thrown back in a wave of ecstasy. A long, indescribable noise of joy was uttered out of its length and breadth. The hymn was taken up by the other creatures, mounting in celebration. Eugene covered his ears and fell to his knees. His nose had begun to bleed at the first notes of the monster's music, and his eyes were full of stinging tears. He wasn't frightened. He knew they were not capable of doing him harm. He cried because he had ignored this eventuality for six years, and now, with their mystery and their glory in front of him, he sobbed not to have had the courage to face them and know them. Now it was too late. They'd taken the boy by force, and reduced his house, and his life, to ruins. Indifferent to his agonies, they were leaving, singing their jubilation, his boy in their arms forever.

In the township of Welcome organization was the by-word of the day. Davidson could only watch with admiration the way these foolish, hardy people were attempting to confront impossible odds. He was strangely enervated by the spectacle; like watching settlers, in some movie, preparing to muster paltry weaponry and simple faith to meet the pagan violence of the savage. But, unlike the movie, Davidson knew defeat was pre-ordained. He'd seen these monsters: awe-inspiring. Whatever the rightness of the cause, the purity of the faith, the savages trampled the settlers underfoot fairly often. The defeats just make it into the movies.

Eugene's nose ceased to bleed after half an hour or so, but he didn't notice. He was dragging, pulling, cajoling Lucy towards Welcome. He wanted to hear no explanations from the slut, even though her voice was babbling ceaselessly. He could only hear the sound of the monsters' churning tones, and Aaron's repeated call of ‘Papa', that was answered by a house-wrecking limb.

Eugene knew he had been conspired against, though even in his most tortured imaginings he could not grasp the whole truth.

Aaron was mad, he knew that much. And somehow his wife, his ripe-bodied Lucy, who had been such a beauty and such a comfort, was instrumental in both the boy's insanity and his own grief.

She'd sold the boy: that was his half-formed belief. In some unspeakable way she had bargained with these things from the underworld, and had exchanged the life and sanity of his only son for some kind of gift. What had she gained, for this payment? Some trinket or other that she kept buried in her shack? My God, she would suffer for it. But before he made her suffer, before he wrenched her hair from its holes, and tarred her flashing breasts with pitch, she would confess. He'd make her confess; not to him but to the people of W

elcome — the men and women who scoffed at his drunken ramblings, laughed when he wept into his beer. They would hear, from Lucy's own lips, the truth behind the nightmares he had endured, and learn, to their horror, that demons he talked about were real. Then he would be exonerated, utterly, and the town would take him back into its bosom asking for his forgiveness, while the feathered body of his bitch-wife swung from a telephone pole outside the town's limits.

They were two miles outside Welcome when Eugene stopped.

"Something's coming."

A cloud of dust, and at its swirling heart a multitude of burning eyes.

He feared the worst.

"My Christ!"

He loosed his wife. Were they coming to fetch her too? Yes, that was probably another part of the bargain she'd made.

"They've taken the town," he said. The air was full of their voices; it was too much to bear.

They were coming at him down the road in a whining horde, driving straight at him — Eugene turned to run, letting the slut go. They could have her, as long as they left him alone; Lucy was smiling into the dust.

"It's Packard," she said.

Eugene glanced back along the road and narrowed his eyes. The cloud of divils was resolving itself. The eyes at its heart were headlights, the voices were sirens; there was an army of cars and motorcycles, led by Packard's howling vehicle, careering down the road from Welcome.

Eugene was confounded. What was this, a mass exodus? Lucy, for the first time that glorious day, felt a twinge of doubt.

As it approached, the convoy slowed, and came to a halt; the dust settled, revealing the extent of Packard's kamikaze squad. There were about a dozen cars and half a dozen bikes, all of them loaded with police and weapons.

A smattering of Welcome citizens made up the army, among them Eleanor Kooker. An impressive array of mean-minded, well-armed people.

Packard leant out of his car, spat, and spoke.

"Got problems, Eugene?" he asked.

"I'm no fool, Packard," said Eugene.

"Not saying you are."

"I seen these things. Lucy'll tell you."

"I know you have, Eugene; I know you have. There's no denying that there's divils in them hills, sure as shit. What'd you think I've got this posse together for, if it ain't divils?"

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

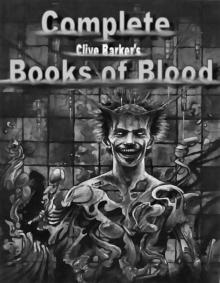

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

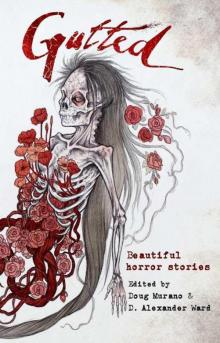

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

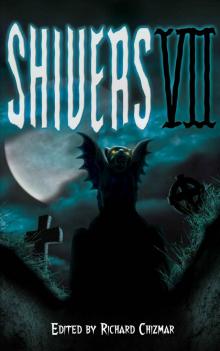

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

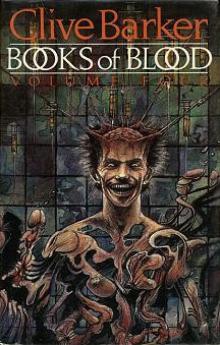

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4