- Home

- Clive Barker

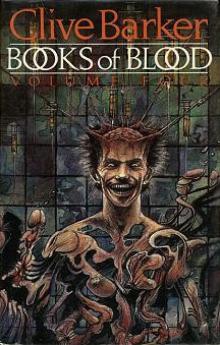

Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Read online

Books Of Blood Vol 1

Clive Barker

Clive Barker

Books Of Blood Vol 1

Every body is a book of blood;

Wherever we’re opened, we’re red.

To my mother and father

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks must go to a variety of people. To my English tutor in Liverpool, Norman Russell, for his early encouragement; Pete Atkins, Julie Blake, Doug Bradley and Oliver Parker for their good advice; to Bill Henry, for his professional eye; to Ramsey Cambell for his generosity and enthusiasm; to Mary Roscoe, for painstaking translation from my hieroglyphics, and to Marie-Noelle Dada for the same; to Vernon Conway and Bryn Newton for faith, Hope and charity; and to Nanndu Sautoy and Barbara Boote at Sphere Books.

INTRODUCTION by Ramsey Campbell

THE CREATURE HAD taken hold of his lip and pulled his muscle off his bone, as though removing a Balaclava.’ Still with me?

Here’s another taste of what you can expect from Clive Barker: ‘Each man, woman and child in that seething tower was sightless. They saw only through the eyes of the city. They were thoughtless, but to think the city’s thoughts. And they believed themselves deathless, in their lumbering, relentless strength. Vast and mad and deathless.’

You see that Barker is as powerfully visionary as he is gruesome. One more quote, from yet another story:

‘What would a Resurrection be without a few laughs?’

I quote that deliberately, as a warning to the faint-hearted. If you like your horror fiction reassuring, both unreal enough not to be taken too seriously and familiar enough not to risk spraining your imagination or waking up your nightmares when you thought they were safely put to sleep, these books are not for you. If, on the other hand, you’re tired of tales that tuck you up and make sure the night light is on before leaving you, not to mention the parade of Good Stories Well Told which have nothing more to offer than borrowings from better horror writers whom the best-seller audience have never heard of, you may rejoice as I did to discover that Clive Barker is the most original writer of horror fiction to have appeared for years, and in the best sense, the most deeply shocking writer now working in the field.

The horror story is often assumed to be reactionary. Certainly some of its finest practitioners have been, but the tendency has also produced a good deal of irresponsible nonsense, and there is no reason why the whole field should look backward. When it comes to the imagination, the only rules should be one’s own instincts, and Clive Barker’s never falter. To say (as some horror writers argue, it seems to me defensively) that horror fiction is fundamentally concerned with reminding us what is normal, if only by showing the supernatural and alien to be abnormal, is not too far from saying (as quite a few publishers’ editors apparently think) that horror fiction must be about ordinary everyday people confronted by the alien. Thank heaven nobody convinced Poe of that, and thank heaven for writers as radical as Clive Barker.

Not that he’s necessarily averse to traditional themes, but they come out transformed when he’s finished with them. ‘Sex, Death and Starshine’ is the ultimate haunted theatre story, ‘Human Remains’ is a brilliantly original variation on the doppelganger theme, but both these take familiar themes further than ever before, to conclusions that are both blackly comic and weirdly optimistic. The same might be said of ‘New Murders in the Rue Morgue’, a dauntingly optimistic comedy of the macabre, but now we’re in the more challenging territory of Barker’s radical sexual openness. What, precisely, this and others of his tales are saying about possibilities, I leave for you to judge. I did warn you that these books are not for the faint of heart and imagination, and it’s as well to keep that in mind while braving such tales as ‘Midnight Meat-Train’, a Technicolor horror story rooted in the graphic horror movie but wittier and more vivid than any of those. ‘Scape-Goats’, his island tale of terror, actually uses that staple of the dubbed horror film and videocassette, the underwater zombie, and ‘Son of Celluloid’ goes straight for a biological taboo with a directness worthy of the films of David Cronenberg, but it’s worth pointing out that the real strength of that story is its flow of invention. So it is with tales such as ‘In the Hills, the Cities’ (which gives the lie to the notion, agreed to by too many horror writers, that there are no original horror stories) and ‘The Skins of the Fathers’. Their fertility of invention recalls the great fantastic painters, and indeed I can’t think of a contemporary writer in the field whose work demands more loudly to be illustrated. And there’s more: the terrifying ‘Pig-Blood Blues’; ‘Dread’, which walks the shaky tightrope between clarity and voyeurism that any treatment of sadism risks; more, but I think it’s almost time I got out of your way.

Here you have nearly a quarter of a million words of him (at least, I hope you’ve bought all three volumes; he’d planned them as a single book), his choice of the best of eighteen months’ worth of short stories, written in the evenings while during the days he wrote plays (which, by the way, have played to full houses). It seems to me to be an astonishing performance, and the most exciting debut in horror fiction for many years.

Merseyside, 5 May 1983

THE BOOK OF BLOOD

THE DEAD HAVE highways.

They run, unerring lines of ghost-trains, of dream-carriages, across the wasteland behind our lives, bearing an endless traffic of departed souls. Their thrum and throb can be heard in the broken places of the world, through cracks made by acts of cruelty, violence and depravity. Their freight, the wandering dead, can be glimpsed when the heart is close to bursting, and sights that should be hidden come plainly into view.

They have sign-posts, these highways, and bridges and lay-bys. They have turnpikes and intersections.

It is at these intersections, where the crowds of dead mingle and cross, that this forbidden highway is most likely to spill through into our world. The traffic is heavy at the cross-roads, and the voices of the dead are at their most shrill. Here the barriers that separate one reality from the next are worn thin with the passage of innumerable feet.

Such an intersection on the highway of the dead was located at Number 65, Tollington Place. Just a brick--fronted, mock-Georgian detached house, Number 65 was unremarkable in every other way. An old, forgettable house, stripped of the cheap grandeur it had once laid claim to, it had stood empty for a decade or more.

It was not rising damp that drove tenants from Number 65. It was not the rot in the cellars, or the subsidence that had opened a crack in the front of the house that ran from doorstep to eaves, it was the noise of passage. In the upper storey the din of that traffic never ceased. It cracked the plaster on the walls and it warped the beams. It rattled the windows. It rattled the mind too. Number 65, Tollington Place was a haunted house, and no-one could possess it for long without insanity setting in.

At some time in its history a horror had been committed in that house. No-one knew when, or what. But even to the untrained observer the oppressive atmosphere of the house, particularly the top storey, was unmistakable. There was a memory and a promise of blood in the air of Number 65, a scent that lingered in the sinuses, and turned the strongest stomach. The building and its environs were shunned by vermin, by birds, even by flies. No woodlice crawled in its kitchen, no starling had nested in its attic. Whatever violence had been done there, it had opened the house up, as surely as a knife slits a fish’s belly; and through that cut, that wound in the world, the dead peered out, and had their say. That was the rumour anyway. It was the third week of the investigation at 65, Tollington Place. Three weeks of unprecedented success in the realm of the paranormal. Using a newcomer to the business, a twenty-year-old called Simon McNeal, as a medium, the Essex University Parapsychology

Unit had recorded all but incontrovertible evidence of life after death.

In the top room of the house, a claustrophobic corridor of a room, the McNeal boy had apparently summoned the dead, and at his request they had left copious evidence of their visits, writing in a hundred different hands on the pale ochre walls. They wrote, it seemed, whatever came into their heads. Their names, of course, and their birth and death dates. Fragments of memories, and well-wishes to their living descendants, strange elliptical phrases that hinted at their present torments and mourned their lost joys. Some of the hands were square and ugly, some delicate and feminine. There were obscene drawings and half-finished jokes alongside lines of romantic poetry. A badly drawn rose. A game of noughts and crosses. A shopping list.

The famous had come to this wailing wall — Mussolini was there, Lennon and Janis Joplin — and nobodies too, forgotten people, had signed themselves beside the greats. It was a roll-call of the dead, and it was growing day by day, as though word of mouth was spreading amongst the lost tribes, and seducing them out of silence to sign this barren room with their sacred presence. After a lifetime’s work in the field of psychic research, Doctor Florescu was well accustomed to the hard facts of failure. It had been almost comfortable, settling back into a certainty that the evidence would never manifest itself. Now, faced with a sudden and spectacular success, she felt both elated and confused.

She sat, as she had sat for three incredible weeks, in the main room on the middle floor, one flight of stairs down from the writing room, and listened to the clamour of noises from upstairs with a sort of awe, scarcely daring to believe that she was allowed to be present at this miracle. There had been nibbles before, tantalizing hints of voices from another world, but this was the first time that province had insisted on being heard.

Upstairs, the noises stopped. Mary looked at her watch: it was six-seventeen p.m.

For some reason best known to the visitors, the contact never lasted much after six. She’d wait ‘til half-past then go up. What would it have been today? Who would have come to that sordid little room, and left their mark?

‘Shall I set up the cameras?’ Reg Fuller, her assistant, asked.

‘Please,’ she murmured, distracted by expectation.

‘Wonder what we’ll get today?’

‘We’ll leave him ten minutes.’

‘Sure.’

Upstairs, McNeal slumped in the corner of the room, and watched the October sun through the tiny window. He felt a little shut in, all alone in that damn place, but he still smiled to himself, that warm, beatific smile that melted even the most academic heart. Especially Doctor Florescu’s: oh yes, the woman was infatuated with his smile, his eyes, the lost look he put on for her. It was a fine game.

Indeed, at first that was all it had been — a game. Now Simon knew they were playing for bigger stakes; what had begun as a sort of lie-detection test had turned into a very serious contest: McNeal versus the Truth. The truth was simple: he was a cheat. He penned all his ‘ghost-writings’ on the wall with tiny shards of lead he secreted under his tongue: he banged and thrashed and shouted without any provocation other than the sheer mischief of it: and the unknown names he wrote, ha, he laughed to think of it, the names he found in telephone directories.

Yes, it was indeed a fine game.

She promised him so much, she tempted him with fame, encouraging every lie that he invented. Promises of wealth, of applauded appearances on the television, of an adulation he’d never known before. As long as he produced the ghosts. He smiled the smile again. She called him her Go-Between: an innocent carrier of messages. She’d be up the stairs soon — her eyes on his body, his voice close to tears with her pathetic excitement at another series of scrawled names and nonsense.

He liked it when she looked at his nakedness, or all but nakedness. All his sessions were carried out with him only dressed in a pair of briefs, to preclude any hidden aids. A ridiculous precaution. All he needed were the leads under his tongue, and enough energy to fling himself around for half an hour, bellowing his head off.

He was sweating. The groove of his breast-bone was slick with it, his hair plastered to his pale forehead. Today had been hard work: he was looking forward to getting out of the room, sluicing himself down, and basking in admiration awhile. The Go-Between put his hand down his briefs and played with himself, idly. Somewhere in the room a fly, or flies maybe, were trapped. It was late in the season for flies, but he could hear them somewhere close. They buzzed and fretted against the window, or around the light bulb. He heard their tiny fly voices, but didn’t question them, too engrossed in his thoughts of the game, and in the simple delight of stroking himself.

How they buzzed, these harmless insect voices, buzzed and sang and complained. How they complained.

Mary Florescu drummed the table with her fingers. Her wedding ring was loose today, she felt it moving with the rhythm of her tapping. Sometimes it was tight and sometimes loose: one of those small mysteries that she’d never analysed properly but simply accepted. In fact today it was very loose: almost ready to fall off. She thought of Alan’s face. Alan’s dear face. She thought of it through a hole made of her wedding ring, as if down a tunnel. Was that what his death had been like: being carried away and yet further away down a tunnel to the dark? She thrust the ring deeper on to her hand. Through the tips of her index-finger and thumb she seemed almost to taste the sour metal as she touched it. It was a curious sensation, an illusion of some kind.

To wash the bitterness away she thought of the boy. His face came easily, so very easily, splashing into her consciousness with his smile and his unremarkable physique, still unmanly. Like a girl really — the roundness of him, the sweet clarity of his skin — the innocence.

Her fingers were still on the ring, and the sourness she had tasted grew. She looked up. Fuller was organizing the equipment. Around his balding head a nimbus of pale green light shimmered and wove —She suddenly felt giddy.

Fuller saw nothing and heard nothing. His head was bowed to his business, engrossed. Mary stared at him still, seeing the halo on him, feeling new sensations waking in her, coursing through her. The air seemed suddenly alive: the very molecules of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen jostled against her in an intimate embrace. The nimbus around Fuller’s head was spreading, finding fellow radiance in every object in the room. The unnatural sense in her fingertips was spreading too. She could see the colour of her breath as she exhaled it: a pinky orange glamour in the bubbling air. She could hear, quite clearly, the voice of the desk she sat at: the low whine of its solid presence.

The world was opening up: throwing her senses into an ecstasy, coaxing them into a wild confusion of functions. She was capable, suddenly, of knowing the world as a system, not of politics or religions, but as a system of senses, a system that spread out from the living flesh to the inert wood of her desk, to the stale gold of her wedding ring.

And further. Beyond wood, beyond gold. The crack opened that led to the highway. In her head she heard voices that came from no living mouth.

She looked up, or rather some force thrust her head back violently and she found herself staring up at the ceiling. It was covered with worms. No, that was absurd! It seemed to be alive, though, maggoty with life — pulsing, dancing.

She could see the boy through the ceiling. He was sitting on the floor, with his jutting member in his hand. His head was thrown back, like hers. He was as lost in his ecstasy as she was. Her new sight saw the throbbing light in and around his body — traced the passion that was seated in his gut, and his head molten with pleasure.

It saw another sight, the lie in him, the absence of power where she’d thought there had been something wonderful. He had no talent to commune with ghosts, nor had ever had, she saw this plainly. He was a little liar, a boy-liar, a sweet, white boy-liar without the compassion or the wisdom to understand what he had dared to do.

Now it was done. The lies were told, the tricks were played, and the peop

le on the highway, sick beyond death of being misrepresented and mocked, were buzzing at the crack in the wall, and demanding satisfaction.

That crack she had opened: she had unknowingly fin-gered and fumbled at, unlocking it by slow degrees. Her desire for the boy had done that: her endless thoughts of him, her frustration, her heat and her disgust at her heat had pulled the crack wider. Of all the powers that made the system manifest, love, and its companion, passion, and their companion, loss, were the most potent. Here she was, an embodiment of all three. Loving, and wanting, and sensing acutely the impossibility of the former two. Wrapped up in an agony of feeling which she had denied herself, believing she loved the boy simply as her Go-Between.

It wasn’t true! It wasn’t true! She wanted him, wanted him now, deep inside her. Except that now it was too late. The traffic could be denied no longer: it demanded, yes, it demanded access to the little trickster.

She was helpless to prevent it. All she could do was utter a tiny gasp of horror as she saw the highway open out before her, and understood that this was no common intersection they stood at.

Fuller heard the sound.

‘Doctor?’ He looked up from his tinkering and his face — washed with a blue light she could see from the corner of her eye — bore an expression of enquiry.

‘Did you say something?’ he asked.

She thought, with a fillip of her stomach, of how this was bound to end.

The ether-faces of the dead were quite clear in front of her. She could see the profundity of their suffering and she could sympathize with their ache to be heard.

She saw plainly that the highways that crossed at Tollington Place were not common thoroughfares. She was not staring at the happy, idling traffic of the ordinary dead. No, that house opened onto a route walked only by the victims and the perpetrators of violence. The men, the women, the children who had died enduring all the pains nerves had wit to muster, with their minds branded by the circumstances of their deaths. Eloquent beyond words, their eyes spoke their agonies, their ghost bodies still bearing the wounds that had killed them. She could also see, mingling freely with the innocents, their slaughterers and tormentors. These monsters, frenzied, mush-minded blood-letters, peeked through into the world: nonesuch creatures, unspoken, forbidden miracles of our species, chattering and howling their Jabberwocky.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

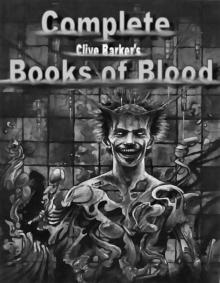

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4