- Home

- Clive Barker

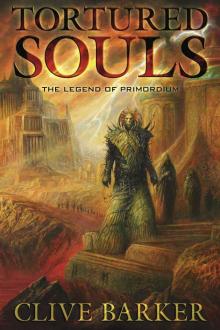

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Read online

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Copyright © 2001 by Clive Barker.

All rights reserved.

Dust jacket and interior illustrations

Copyright © 2015 by Bob Eggleton.

All rights reserved.

Print Interior design

Copyright © 2015 by Desert Isle Design, LLC.

All rights reserved.

First Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-636-6

Ebook ISBN

978-1-59606-637-7

Subterranean Press

PO Box 190106

Burton, MI 48519

subterraneanpress.com

I

He is a transformer of human flesh; a creator of monsters. If a Supplicant comes to him with sufficient need, sufficient hunger for change—knowing how painful that change will be—he will accommodate them. They become objects of perverse beauty beneath his hand; their bodies remade in fashions that they have no power to dictate.

Over the years, over the centuries, indeed, this extraordinary creature has gone by many names. But we will call him by the first name he was ever given: AGONISTES.

Where would a Supplicant find him? Usually in what he calls ‘the burning places’: deserts, for instance. But sometimes he can be found in ‘the burning places’ in our own inflamed cities: places where despair has seared away all belief in hope and love.

There he moves, silently, irreproachably, his presence barely more than a rumour. And there he waits for those who need him to come to find him.

When a Supplicant presents him or herself there is never coercion. There is never violence, at least until the Supplicant has signed over his or her flesh. Then yes, there may be some second thoughts, once the work begins. The truth is that on many occasions a Supplicant has begged to die rather than continue to be ‘empowered’ by Agonistes. It hurts too much, they tell him, as his scalpels and his torches work their terrible surgery upon him. But in all the time he has been wandering the world Agonistes has only ever granted the comfort of death to one Supplicant who changed his mind. That man was Judas Iscariot, who whined so much Agonistes hanged him from a tree. The rest he works on despite their complaints, sometimes for days and nights, coming back to his labours when a piece of flesh has healed and he can begin on the next part of the surgery.

There are some minor compensations for all this pain, which Agonistes will sometimes offer his Supplicants as he works. He will sing to them, for instance, and it is said that he knows every lullaby written, in every language of the world; songs of the cradle and the breast, to soothe the men and women he is remaking in the image of their terror.

And, if for some reason he feels particularly sympathetic to the Supplicant, Agonistes may even give his victim a piece of his own flesh to eat: just a sliver, cut with one of his finest scalpels, from the tender flesh of his upper thigh, or inner lip. According to legend, there is no food more comforting, more exquisite, than the flesh of Agonistes. The merest sliver of it upon the tongue of the Supplicant will make him or her forget all the horrors they are enduring, and deliver them to a place of paradisical calm.

Then once his client is soothed Agonistes continues his work, cutting, infibulating, searing, cauterizing, stretching, twisting, reconfiguring.

Sometimes he will bring a mirror to show his Supplicants what he has so far created. Sometimes he will announce that he wants the results to be a surprise; and so the Supplicant is left to imagine, through the haze of pain, what Agonistes is turning them into.

II

It is an art, what Agonistes achieves.

He claims it is The First Art, this creation of new flesh, being the art God used to call life into being. Agonistes believes in God; prays to Him night and morning: thanking Him for making a world in which there is so much hopelessness and such a profound hunger for revenge that Supplicants will seek him out and beg him to reconfigure them in the image of their monstrous ideal.

And it appears that God apparently finds no offence in what Agonistes does, because for two and a half thousand years he has walked the planet, performing what he calls his holy art, and no harm has come to him. In fact he has prospered.

Some of the people who went under his knife, like Pontius Pilate, have a place in our culture’s history. Many are anonymous. He has transformed potentates and gangsters, failed actors and architects; women who’ve been cheated by their husbands and come seeking a new form to greet their adulterer in their marriage beds; school mistresses and perfumiers, dog-trainers and charcoal burners. The mighty and the insignificant, the noble and the peasant. As long as they are sincere Supplicants, and their prayers sound genuine, then Agonistes will be attentive to them.

Who is he, this Agonistes? This artist, this wanderer, this transformer of human flesh and bone?

In truth, nobody really knows. There is a heretical volume in the Vatican Library called ‘A Treatise on the Madness of God’, written by one Cardinal Gaillema in the mid-seventeenth century. In it, Gaillema argues that the account of the Creation of the world offered in the Book of Genesis is wrong in several particulars, one of which is relevant here: on the seventh day, the Cardinal argued, God did not rest. Instead, driven into a kind of ecstatic fugue state by the labours of His Creation, God continued to work. But the creations He summoned up in His exhausted state were not the wholesome beasts with which He had populated Eden. In one day and one night, wandering amongst the fresh glories of creation, He summoned up forms that defied all the beauty of his early work. Destroyers and demons, these were the antitheses of the wholesome forms that He had made in the first six days.

One of the creatures Jehovah created, the Cardinal claims, was Agonistes. That’s why Agonistes can pray to His Father in Heaven, and expect to be listened to. He is—at least according to Cardinal Gaillema’s account—one of God’s own creations.

And there is no doubt that in his perverse way Agonistes serves a function. Over the years, over the centuries, he has been the answer to countless prayers for deliverance from powerlessness.

The words may change from prayer to prayer, but the meat of them is always the same:

“O Agonistes, dark deliverer, make me in the image of my enemies’ nightmares. Let my flesh be the stuff from which you carve their terrors; let my skull be a bell which sounds their death-knell. Give me a song to sing, which will be the song of their despair, and let them wake and find me singing it at the bottom of their beds.”

“Unmake me, unknit me, transform me.”

“And if you cannot do that for me, Agonistes, then let me be excrement; let me be nothing; less than nothing.”

“For I want to be the terror of my enemies, or I want oblivion.”

“The choice, Lord, is yours.”

I

The city of Primordium was founded before any of the great cities of myth or history. Indeed, it is, according to many sources, the first city ever built. Before Troy, before Rome, before Jerusalem, there was Primordium.

Until recently it was ruled by a dynasty of Emperors, whose long tenure had steadily produced a capacity for cruelty that would have challenged the worst excesses of Rome’s corrupted Caesars. The Emperor Perfetto XI, for instance, who controlled Primordium for sixteen years until the Great Insurrection, was a man familiar with every corruption of mind and spirit. He lived in excessive luxury, in a palace he believed impregnable, caring little or nothing for the two and three quarter million people who occupied Primordium.

In the end, that was his undoing.

But we’ll come to that.

II

First, let me tell you about Zarles Kreiger, who

came from the lowest strata of the city. As a child, it was common for him to eat at the Vomitorium, where—as in ancient Rome—the rich food disgorged by the wealthy and overfed could be purchased for a small amount of money, and consumed a second time. It was Kreiger’s good fortune that such a life of poverty did not kill him. By some physical paradox, experiences that would have reduced most men to shadows of their former selves, served to strengthen Zarles. By the time he was thirteen he was already larger than all his older brothers. And along with his physical prowess came something else: a curiosity about how the infinitely corrupt city in which he lived actually worked.

At the age of fourteen he became a runner for a gangster in the East City called Duraf Cascarellian, and quickly elevated himself in the criminal’s employ, simply because he was willing to do anything requested of him. In return, Cascarellian treated Kreiger like a son; protecting him from capture by sending men out after Kreiger to clean up after one of his murders. Kreiger was a messy killer. Not for him the simple slit across the throat. He liked to use scythes, first disembowelling his victims then strangling them with their own entrails.

Now such behaviour does not go unnoticed for long, even in a city as filled with excesses as Primordium. And Kreiger’s reputation was increased considerably by the fact that the hits Cascarellian was having him make were often political. Judges, congressmen, journalists who were critical of the Emperor: these were often Kreiger’s victims. Personally, he cared not at all about the affiliation of his victims. Blood was blood as far as Kreiger was concerned, and he took the same pleasure in it whether it poured from the flesh of a Republican or a Royalist.

Then he met a woman called Lucidique, and all that changed.

III

Lucidique was the daughter of a Senator who had been lately complaining in open forum about the fact that the city was running into a state of decadence. The Perfetto Dynasty was using the people’s taxes to fund its own pleasures, the Senator argued: it had to stop.

The order quickly came down from the Emperor: rid me of this Senator. Cascarellian, not giving a damn about the philosophical issues, but happy to oblige his Emperor, sent Kreiger out to kill the political troublemaker.

Kreiger went to the Senator’s estate, caught him in the garden amongst his roses, gutted him and carried him inside. He was in the act of arranging the Senator’s body on the dinner table, when Lucidique entered. She was naked, having just come from bathing. But she was also prepared for the intruder. She carried two knives.

She circled Kreiger, as he stood amongst the blood and the innards of her father.

“If you move I’ll kill you,” she said.

“With two table knives?” Kreiger said, slicing the air with his scythes. “Go back to your bath and forget I was here.”

“This was my father you just murdered!”

“Yes. I see the resemblance.”

“I would have thought a man like you would have thought twice about taking a knife to my father’s throat. He wanted to overthrow the Empire so that you and your like would not be exploited.”

“Me and my like? You don’t know anything about me.”

“I can guess,” Lucidique said. “You were born in filth, and you’ve lived in filth so long you don’t even see what’s going on right in front of you.”

Kreiger’s expression changed. “So perhaps you do know a little,” he said, his voice uneasy. The woman’s confidence unnerved him. “I will leave you to mourn your father,” he said, retreating from the table.

“Wait!” the woman said. “Not so quickly.”

“What do you mean: wait? I could kill you in a heartbeat if I wanted to.”

“But you don’t want to, or you would have done it.”

“What’s your name?”

“Lucidique.”

“So then, what do you want from me?”

“I want you to come with me, into the filthiest streets of Primordium.”

“Believe me, I’ve seen them.”

“Then you show me.”

IV

It was the strangest walk a man and a woman ever took together. Though Kreiger had washed the Senator’s blood from his face, hands, and arms he still stank of murder. And here he was, walking beside the daughter of the man he’d just murdered, wrapped in dark linen.

Together, they saw the worst of Primordium: the disease, the violence, and the grinding, unrelieved poverty. And every now and then Lucidique would point to the walls and the towers of the Emperor’s Winter Palace, any one room of which contained sufficient wealth to clear the slums of the city, and feed every starving child.

And for the first time in many, many years Kreiger felt some measure of real emotion, remembering circumstances of his own upbringing, left to sit in the open sewers of Primordium’s streets while his mother sold her drug-riddled body to one of the Emperor’s guards. There was anger in him as he walked. And it steadily grew.

“What do you want me to do?” he said, frustrated by what he felt, and his own helplessness. “I could never get to the Emperor.”

“Don’t be so sure.”

“What do you mean?”

“You’re right, the Dynasty is untouchable as long as you’re just a man; a scabby little assassin hired to kill overweight Senators. But suppose you could be more than that? Then you could bring the Dynasty down.”

“How?”

Lucidique gave Kreiger a sideways glance. “It’s nothing I can show you here. Besides, I have a father to bury. If you want to know more, then meet me tomorrow night outside the Western Gates. Come alone.”

“If this is some kind of trap…” Kreiger said, “…some way to revenge your father…then before they take me I’ll cut out your eyes.”

Lucidique smiled. “You make such pretty love-talk,” she said.

“I mean it.”

“I know. And I wouldn’t be so stupid as to conspire against you. Quite the reverse. I believe we were meant to know one another. I was meant to walk in on your killing my father, and you were meant to hold your hand off and not kill me. There’s some connection between us. You feel it, don’t you?”

Kreiger looked at the dirty street between them. The night had been filled with feelings he had not anticipated experiencing. And now here was another; admitting to the strange intimacy he felt for the daughter of the man he’d murdered.

“Yes,” he said. “I feel it.” Then, after a long silence: “What time tomorrow night?”

“Sometime after one,” Lucidique told him. “I’ll be there.”

V

The following day the streets of Primordium were alive with gossip and speculation: the death of the Senator had started all kinds of rumours. Was this murder the first indication that the Emperor would put up with no more moves towards democracy in the city? Believing this to be the case many members of the Senate left Primordium hurriedly, in case, they were next on the Emperor’s hit list. There was a general sense of unrest, everywhere.

And in Kreiger, a profound sense of anticipation.

He had barely slept, thinking of what had happened the night before. No, not just the night before. Thinking about his life: where it had led him so far, and where—if Lucidique’s promise were a true one—it would go after this.

Every now and then he’d glance towards the walls of the palace (which had twice as many guards patrolling them today as yesterday) and wonder to himself what she had meant about finding a way for one man to bring down a Dynasty?

VI

At one o’clock in the morning, a mile outside the West Gate of Primordium, he sat on a stone and he waited. At nine minutes past one, a pair of horses approached (not from the city, from which direction Kreiger had expected her to come, but from the Desert, which lay, vast and largely uncharted, out to the West and South-West of the city).

They drew nearer, and dismounted.

“Kreiger…”

“Yes?”

“I want you to meet Agonistes.”

Kr

eiger had heard rumours about this man Agonistes. It was the kind of story that was exchanged between assassins, more of a legend than a reality.

But here he was. As real as the woman who’d brought him.

“I hear you want to make Primordium a Republic,” Agonistes said. “Single-handed.”

“She persuaded me it was possible,” Kreiger replied. “But…I don’t believe it is.”

“You should have more faith, Kreiger. I can make you the terror of Emperors, if you want it badly enough. It’s up to you. Make up your mind quickly, for I have better business elsewhere tonight if you don’t require my services. I can hear a hundred prayers pouring out of Primordium at this very moment; people wanting me to give them the power to change their world.”

Lucidique put her hand up to Kreiger’s face. “Now the moment’s here, I see you don’t want it,” she said. “You’re afraid.”

“I’m not afraid!” Kreiger said. He thought of his mother, dead of the pox, of his brothers killed in the street as children by noblemen passing on horses, of his sister, in the asylum, never to be sane again.

“Take me,” he said.

“You’re sure?” Agonistes asked him. “Remember, there’s no way back.”

“I don’t want to go back. Take me. Change me.”

He glanced at Lucidique. She was smiling.

“Take the horses,” Agonistes told her. “We won’t need them.”

So together, Kreiger and Agonistes turned round and headed into the desert.

VII

The next day Lucidique buried her father. The rumours quietened down a little in the city, but there was still an undercurrent, subtle but pervasive: Primordium was in a very volatile state; like an explosive, which might be set off with a jolt.

Eight nights after Agonistes had taken Kreiger out into the desert, Lucidique—whose father’s house lay close to the palace—woke to the sounds of screams.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

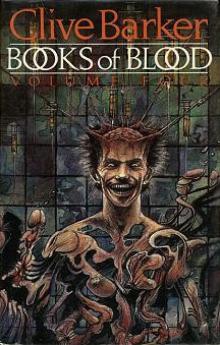

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

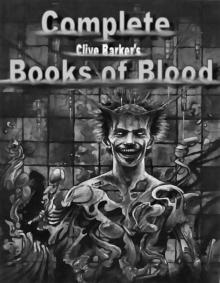

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

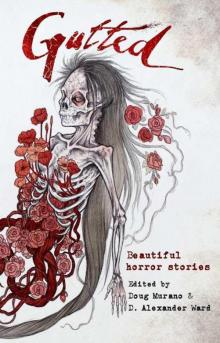

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

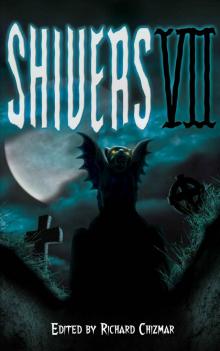

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4