- Home

- Clive Barker

The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Mark, without whom this book would not exist

His friend demanding what scarlet was, the blind man answered: It was like the sound of a trumpet.

—John Locke,

Human Understanding

PROLOGUE

Labor Diabolus

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring—

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

—Sameul Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

1

After the long quiet of the grave, Joseph Ragowski gave voice, and it was not pleasant, in either sound or sentiment.

“Look at you all,” he said, scrutinizing the five magicians who’d woken him from his dreamless sleep. “You look ghostly, every one of you.”

“You don’t look so good yourself, Joe,” Lili Saffro said. “Your embalmer was a little too enthusiastic with the rouge and the eyeliner.”

Ragowski snarled, his hand going up to his cheek and wiping off some of the makeup that had been used to conceal the sickening pallor his violent death had left on him. He’d been hastily embalmed, no doubt, and filed away in his ledge within the family mausoleum, in a cemetery on the outskirts of Hamburg.

“I hope you didn’t go to all this trouble just to take cheap shots at me,” Ragowski said, surveying the paraphernalia that littered the floor around him. “Regardless, I’m impressed. Necromantic workings demanded an obsessive’s eye for detail.”

The N’guize Working, which was the one the magicians had used to raise Ragowski, called for the eggs of pure white doves that had been injected with the blood of a girl’s first menstruation, to be cracked into eleven alabaster bowls surrounding the corpse, each of which contained other obscure ingredients. Purity was of the essence of this working. The birds couldn’t be speckled, the blood had to be fresh, and the two thousand, seven hundred, and nine numerals that were inscribed in black chalk starting beneath the ring of bowls and spiraling inward to the spot where the corpse of the resurrectee was laid had to be in precisely the right order, with no erasures, breaks, or corrections.

“This your work, isn’t it, Elizabeth?” Ragowski said.

The oldest of the five magicians, Elizabeth Kottlove, a woman whose skills in some of the most complex and volatile of magical preservations weren’t enough to keep her face from looking like someone who’d lost both her appetite and her ability to sleep decades ago, nodded.

“Yes,” she said. “We need your help, Joey.”

“It’s a long time since you called me that,” Ragowski said. “And it was usually when you were fucking me. Am I being fucked right now?”

Kottlove threw a quick glance at her fellow magicians—Lili Saffro, Yashar Heyadat, Arnold Poltash, and Theodore Felixson—and saw that they were no more amused by Ragowski’s insults than she was.

“I see that death hasn’t robbed you of your bitter tongue,” she said.

“For fuck’s sake,” said Poltash. “This has been the problem all along! Whatever we did or didn’t do, whatever we had or didn’t have, none of it matters.” He shook his head. “The time we wasted fighting to outdo one another—when we could have been working together—it makes me want to weep.”

“You weep,” said Theodore Felixson. “I’ll fight.”

“Yes. Please. Spare us your tears, Arnold,” Lili said. She was the only one of the five summoners sitting, for the simple reason that she was missing her left leg. “We all wish we could change things—”

“Lili, dear,” Ragowski said, “I can’t help but notice that you’re not quite the woman you were. What’s happened to your leg?”

“Actually,” she said, “I got lucky. He nearly had me, Joseph.”

“He…? You mean he hasn’t been stopped?”

“We’re a dying breed, Joseph,” said Poltash. “A veritable endangered species.”

“How many of the Circle are left?” Joseph said, a sudden urgency in his voice.

There was a silence while the five exchanged hesitant looks. It was Kottlove who finally spoke.

“We are all that is left,” she said, staring at one of the alabaster bowls and its bloodstained contents.

“You? Five? No.” All the sarcasm and the petty game playing had gone from Ragowski’s voice and manner. Even the embalmer’s bright paints could not moderate the horror on Ragowski’s face. “How long have I been dead?”

“Three years,” Kottlove said.

“This has to be a joke. How is that possible?” Ragowski said. “There were two hundred and seventy-one in the High Circle alone!”

“Yes,” said Heyadat. “And that’s only those who chose to be counted among us. There’s no telling how many he took from outside the Circles. Hundreds? Thousands?”

“And no telling what they owned either,” Lili Saffro said. “We had a reasonably thorough list—”

“But even that wasn’t complete,” Poltash said. “We all have our secret possessions. I know I do.”

“Ah … too true,” Felixson said.

“Five…” Ragowski said, shaking his head. “Why couldn’t you put your heads together and work out some way to stop him?”

“That’s why we went to all the trouble of bringing you back,” Heyadat said, “Believe me, none of us did it happily. You think we didn’t try to catch the bastard? We fucking tried. But the demon is goddamn clever—”

“And getting cleverer all the time,” Kottlove said. “In a way, you should be flattered. He took you early because he’d done his homework. He knew you were the only one who could unite us all against him.”

“And when you died, we argued and pointed fingers like squabbling schoolchildren.” Poltash sighed. “He picked us off, one by one, moving all over the globe so we never knew where he was going to strike next. A lot of people got taken without anybody knowing a thing about it. We’d hear about it later, usually after a few months. Sometimes even a year. Just by chance. You’d try to make contact with someone and find their house had been sold, or burned to the ground, or simply left to rot. I visited a couple of places like that. Remember Brander’s house in Bali? I went there. And Doctor Biganzoli’s place outside Rome? I went there too. There was no sign of any looting. The locals were far too afraid of what they’d heard about the occupants to take a step inside either house, even despite the fact that it was very obvious nobody was home.”

“What did you find?” Ragowski said.

Poltash took out a pack of cigarettes and lit one as he went on. His hands were trembling, and it took some help from Kottlove to steady the hand that held his lighter.

“Everything of any magical value had vanished. Brander’s urtexts, Biganzoli’s collection of Vatican Apocrypha. Everything down to the most trivial blasphemous pamphlet was gone. The shelves were bare. It was obvious that Brander had put up a struggle; there was a

lot of blood in the kitchen, of all places—”

“Do we really have to go back over all this?” Heyadat said. “We all know how these stories end.”

“You dragged me out of a very welcome death to help save your souls,” Ragoswki said. “The least you can do is let me hear the facts. Arnold, continue.”

“Well, the blood was old. There was a lot of it, but it had dried many months before.”

“Was it the same with Biganzoli?” Ragowski said.

“Biganzoli’s place was still sealed up when I visited. Shutters closed and doors locked as if he’d gone on a long vacation, but he was still inside. I found him in his study. He—Christ, Joseph, he was hanging from the ceiling by chains. They were attached to hooks that had been put through his flesh. And it was so hot in there. My guess is he’d been dead in that dry heat for at least six months. His body was completely withered up. But the expression on his face could have just been the way the flesh had retreated from around his mouth as it dried up, but by God he looked as though he’d died screaming.”

Ragowski studied the faces before him. “So, while you were having your private wars over mistresses and boys, this demon ended the lives and pillaged the minds of the most sophisticated magicians on the planet?”

“In sum?” Poltash said. “Yes.”

“Why? What is his intention? Have you at least discovered that?”

“The same as ours, we think,” Felixson said. “The getting and keeping of power. He hasn’t just taken our treaties, scrolls, and grimoires. He’s cleared out all the vestments, all the talismans, all the amulets—”

“Hush,” Ragowski said suddenly. “Listen.”

There was a silence among them for a moment, and then a funereal bell chimed softly in the distance.

“Oh Christ,” Lili said. “It’s his bell.”

The dead man laughed.

“He’s found you.”

2

The assembled company, excepting the once-deceased Ragowski, instantly loosed a flood of prayers, protestations, and entreaties, no two of which were in the same language.

“Thank you for the gift of second life, old friends,” Ragowski said. “Few people get the pleasure of dying twice, especially by the same executioner.”

Ragowski stepped out of his coffin, kicked over the first of the alabaster bowls, and began working his way around the necromantic circle in a counterclockwise direction. The broken eggs and the menstrual blood, along with the other ingredients of the bowls, each one different but all a vital part of the N’guize Working, were spilled across the floor. One bowl rolled off on its rim, weaving wildly before hitting one of the mausoleum walls.

“That was just childish,” Kottlove said.

“Sweet Jesus,” Poltash said. “The bell is getting louder.”

“We made our peace with one another to get your help and protect ourselves,” Felixson shouted. “Surrender can’t be our only option! I won’t accept it.”

“You made your peace too late,” Ragowski said, bringing his foot down and grinding the broken bowls into a powder. “Maybe if there’d been fifty of you, all sharing your knowledge, you might have had a hope. But, as it stands, you’re outnumbered.”

“Outnumbered? You mean he has functionaries?” Heyadat said.

“Good God. Is it the fog of death, or the years that have passed? I honestly don’t remember you people being this stupid. The demon has imbibed the knowledge of countless minds. He doesn’t need backup. There’s not an incantation in existence that can stop him.”

“It can’t be true!” screamed Felixson.

“I’m sure I would have said the same hopeless thing three years ago, but that was before my untimely demise, Brother Theodore.”

“We should disperse!” Heyadat said. “All in different directions. I’ll head to Paris—”

“You’re not listening, Yashar. It’s too late,” Ragowski said. “You can’t hide from him. I am proof.”

“You’re right,” said Heyadat. “Paris is too obvious. Somewhere more remote, then—”

While Heyadat laid his panicked plans Elizabeth Kottlove, apparently resigned to the reality of her circumstances, took the time to speak conversationally with Ragowski.

“They said they found your body in the Temple of Phemestrion. It seemed an odd place for you to be, Joseph. Did he bring you there?”

Ragowski stopped and looked at her for a moment before saying, “No. It was my own hiding place, actually. There was a room behind the altar. Tiny. Dark. I … I thought I was safe.”

“And he found you anyway.”

Ragowski nodded. Then, trying to keep his tone offhand and failing, he said, “How did I look?”

“I wasn’t there, but by all accounts appalling. He’d left you in your little hidey-hole with his hooks still in you.”

“Did you tell him where all your manuscripts were?” Poltash asked.

“With a hook and chain up through my asshole pulling my stomach down into my bowels, yes, Arnold, I did. I squealed like a rat in a trap. And then he left me there, with that chain slowly disemboweling me, until he’d gone to my house and brought back everything I’d hidden. I wanted so badly to die by that time I remember that I literally begged him to kill me. I gave him information he didn’t even ask for. All I wanted was death. Which I got, finally. And I was never more grateful for anything in my life.”

“Jesus wept!” Felixson yelled. “Look at you all, listening to his babble! We raised the sonofabitch to get some answers, not recount his fucking horror stories.”

“You want answers!” Ragowski snapped. “Here then. Get yourself some paper, and write down the whereabouts of every last grimoire, pamphlet, and article of power you own. Everything. He’s going to get the information anyway, sooner or later. You, Lili—you have the only known copy of Sanderegger’s Cruelties, yes?”

“Maybe—”

“For fuck’s sake, woman!” Poltash said. “He’s trying to help.”

“Yes. I own it,” Lili Saffro said. “It’s in a safe buried below my mother’s coffin.”

“Write it down. The address of the cemetery. The position of the plot. Draw a goddamn blueprint, if you have to. Just make it easy for him. Hopefully he’ll return the favor.”

“I have no paper,” Heyadat said, his voice suddenly shrill and boyish with fear. “Somebody give me a piece of paper!”

“Here,” said Elizabeth, tearing a sheet from an address book she pulled out of her pocket.

Poltash was writing on an envelope, which he had pressed up against the marble wall of the mausoleum. “I don’t see how this saves us from his tampering with our brains,” he said, scribbling furiously.

“It doesn’t, Arnold. It’s merely a gesture of humility. Something none of us have been very familiar with in our lives. But it may—and I make no guarantees—it may hold sway.”

“Oh Christ!” said Heyadat. “I see light between the cracks.”

The magicians glanced up from their scrawling to see what he was talking about.

At the far end of the mausoleum, a cold blue light was piercing the fine cracks between the marble blocks.

“Our visitor is imminent,” said Ragowski. “Elizabeth, dear?”

“Joseph?” she said, failing to glance up from her fevered scribbling.

“Release me, will you, please?”

“In a minute. Let me finish writing.”

“Release me, god damn you!” he said. “I don’t want to be here when he comes. I don’t ever want to see that horrible face of his again!”

“Patience, Joseph,” Poltash said. “We’re only heeding your advice.”

“Someone give me back my death! I can’t go through this again! Nobody should have to!”

The swelling light from beyond the mausoleum wall was now accompanied by a grinding sound as one of the enormous marble blocks, at about head height, slowly pushed itself out of the wall. When it was roughly ten inches clear of the wall, a second block, below

and to the left of the first one, began to move. Seconds later a third, this time to the right and above the first, also began shifting. The glittering silver-blue shafts of light that had begun this unknitting came in wherever there was a crack for them to steal through.

Ragowski, enraged at the indifference of his resurrectors, resumed the destruction of Kottlove’s necromantic labors where he’d left off. He grabbed the alabaster bowls and hurled them against the moving wall. Then, pulling off the jacket he’d been buried in, he got down on his knees and used it to scrub out the numbers Kottlove had scrawled in the immaculate spiral. Dead though he was, beads of fluid appeared on his brow as he scrubbed. It was a dark, thick liquid that collected at his forehead and finally fell from his face and spattered on the ground, a mingling of embalming fluid and some remnants of his own corrupted juices. But his effort to undo the resurrection began to pay off. A welcome numbness started spreading from his fingers and toes up into his limbs, and a lolling weight gathered behind his eyes and sinuses, as the semi-liquefied contents of his skull responded to the demands of gravity.

Glancing up from his work, he saw the five magicians scrawling madly like students racing to finish a vital examination paper before the tolling of the bell. Except, of course, the price of failure was rather worse than a bad mark. Ragowski’s gaze went from their toil to the wall, where six blocks were now on the move. The first of the six marble blocks that had responded to the pressure from the other side finally slid clear of the wall and dropped to the ground. A shaft of frigid light, lent solidity by the marble cement dust that hung in the air from the unseated block, spilled from the hole and crossed the length of the mausoleum, striking the opposite wall. The second block dropped only moments later.

Theodore Felixson began to pray aloud as he wrote, the divinity at his prayer’s destination usefully ambiguous:

“Thine the power,

Thine the judgment.

Take my soul, Lord.

Shape and use it.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

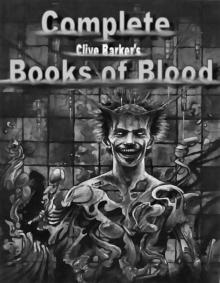

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

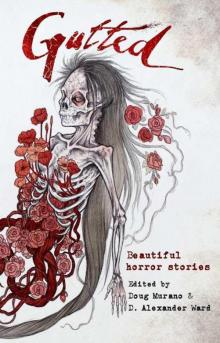

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

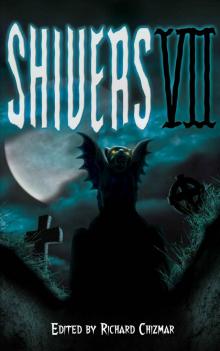

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

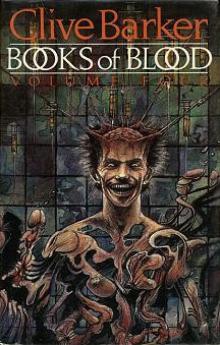

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4