- Home

- Clive Barker

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Page 2

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Read online

Page 2

Now the boy above her sensed them. She saw him turn a little in the silent room, knowing that the voices he heard were not fly-voices, the complaints were not insect-complaints. He was aware, suddenly, that he had lived in a tiny corner of the world, and that the rest of it, the Third, Fourth and Fifth Worlds, were pressing at his lying back, hungry and irrevocable. The sight of his panic was also a smell and a taste to her. Yes, she tasted him as she had always longed to, but it was not a kiss that married their senses, it was his growing panic. It filled her up: her empathy was total. The fearful glance was hers as much as his — their dry throats rasped the same small word:

‘Please —‘

That the child learns. ‘Please —, That wins care and gifts.

‘Please —‘

That even the dead, surely, even the dead must know and obey.

‘Please —,

Today there would be no such mercy given, she knew for certain. These ghosts had despaired on the highway a grieving age, bearing the wounds they had died with, and the insanities they had slaughtered with. They had endured his levity and insolence, his idiocies, the fabrications that had made a game of their ordeals. They wanted to speak the truth.

Fuller was peering at her more closely, his face now swimming in a sea of pulsing orange light. She felt his hands on her skin. They tasted of vinegar.

‘Are you all right?’ he said, his breath like iron.

She shook her head.

No, she was not all right, nothing was right.

The crack was gaping wider every second: through it she could see another sky, the slate heavens that loured over the highway. It overwhelmed the mere reality of the house. ‘Please,’ she said, her eyes rolling up to the fading substance of the ceiling. Wider. Wider —The brittle world she inhabited was stretched to breaking point.

Suddenly, it broke, like a dam, and the black waters poured through, inundating the room.

Fuller knew something was amiss (it was in the colour of his aura, the sudden fear), but he didn’t understand what was happening. She felt his spine ripple: she could see his brain whirl.

‘What’s going on?’ he said. The pathos of the enquiry made her want to laugh.

Upstairs, the water-jug in the writing room shattered.

Fuller let her go and ran towards the door. It began to rattle and shake even as he approached it, as though all the inhabitants of hell were beating on the other side. The handle turned and turned and turned. The paint blistered. The key glowed red-hot. Fuller looked back at the Doctor, who was still fixed in that grotesque position, head back, eyes wide.

He reached for the handle, but the door opened before he could touch it. The hallway beyond had disappeared altogether. Where the familiar interior had stood the vista of the highway stretched to the horizon. The sight killed Fuller in a moment. His mind had no strength to take the panorama in — it could not control the overload that ran through his every nerve. His heart stopped; a revolution overturned the order of his system; his bladder failed, his bowels failed, his limbs shook and collapsed. As he sank to the floor his face began to blister like the door, and his corpse rattle like the handle. He was inert stuff already: as fit for this indignity as wood or steel.

Somewhere to the East his soul joined the wounded highway, on its route to the intersection where a moment previously he had died. Mary Florescu knew she was alone. Above her the marvellous boy, her beautiful, cheating child, was writhing and screeching as the dead set their vengeful hands on his fresh skin. She knew their intention: she could see it in their eyes — there was nothing new about it. Every history had this particular torment in its tradition. He was to be used to record their testaments. He was to be their page, their book, the vessel for their autobiographies. A book of blood. A book made of blood. A book written in blood. She thought of the grimoires that had been made of dead human skin: she’d seen them, touched them. She thought of the tattooes she’d seen: freak show exhibits some of them, others just shirtless labourers in the Street with a message to their mothers pricked across their backs. It was not unknown, to write a book of blood.

But on such skin, on such gleaming skin — oh God, that was the crime. He screamed as the torturing needles of broken jug-glass skipped against his flesh, ploughing it up. She felt his agonies as if they had been hers, and they were not so terrible.

Yet he screamed. And fought, and poured obscenities out at his attackers. They took no notice. They swarmed around him, deaf to any plea or prayer, and worked on him with all the enthusiasm of creatures forced into silence for too long. Mary listened as his voice wearied with its complaints, and she fought against the weight of fear in her limbs. Somehow, she felt, she must get up to the room. It didn’t matter what was beyond the door or on the stairs —he needed her, and that was enough.

She stood up and felt her hair swirl up from her head, flailing like the snake hair of the Gorgon Medusa. Reality swam — there was scarcely a floor to be seen beneath her. The boards of the house were ghost-wood, and beyond them a seething dark raged and yawned at her. She looked to the door, feeling all the time a lethargy that was so hard to fight off. Clearly they didn’t want her up there. Maybe, she thought, they even fear me a little. The idea gave her resolution; why else were they bothering to intimidate her unless her very presence, having once opened this hole in the world, was now a threat to them?

The blistered door was open. Beyond it the reality of the house had succumbed completely to the howling chaos of the highway. She stepped through, concentrating on the way her feet still touched solid floor even though her eyes could no longer see it. The sky above her was prussian-blue, the highway was wide and windy, the dead pressed on every side. She fought through them as through a crowd of living people, while their gawping, idiot faces looked at her and hated her invasion.

The ‘please’ was gone. Now she said nothing; just gritted her teeth and narrowed her eyes against the highway, kicking her feet forward to find the reality of the stairs that she knew were there. She tripped as she touched them, and a howl went up from the crowd. She couldn’t tell if they were laughing at her clumsiness, or sounding a warning at how far she had got.

First step. Second step. Third step.

Though she was torn at from every side, she was winning against the crowd. Ahead she could see through the door of the room to where her little liar was sprawled, surrounded by his attackers. His briefs were around his ankles: the scene looked like a kind of rape. He screamed no longer, but his eyes were wild with terror and pain. At least he was still alive. The natural resilience of his young mind had half accepted the spectacle that had opened in front of him.

Suddenly his head jerked around and he looked straight through the door at her. In this extremity he had dredged up a true talent, a skill that was a fraction of Mary’s, but enough to make contact with her. Their eyes met. In a sea of blue darkness, surrounded on every side with a civilization they neither knew nor understood, their living hearts met and married.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said silently. It was infinitely pitiful. ‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry.’ He looked away, his gaze wrenched from hers.

She was certain she must be almost at the top of the stairs, her feet still treading air as far as her eyes could tell, the faces of the travellers above, below and on every side of her. But she could see, very faintly, the outline of the door, and the boards and beams of the room where Simon lay. He was one mass of blood now, from head to foot. She could see the marks, the hieroglyphics of agony on every inch of his torso, his face, his limbs. One moment he seemed to flash into a kind of focus, and she could see him in the empty room, with the sun through the window, and the shattered jug at his side. Then her concentration would falter and instead she’d see the invisible world made visible, and he’d be hanging in the air while they wrote on him from every side, plucking out the hair on his head and body to clear the page, writing in his armpits, writing on his eyelids, writing on his genitals, in the crease of his buttocks

, on the soles of his feet.

Only the wounds were in common between the two sights. Whether she saw him beset with authors, or alone in the room, he was bleeding and bleeding.

She had reached the door now. Her trembling hand stretched to touch the solid reality of the handle, but even with all the concentration she could muster it would not come clear. There was barely a ghost-image for her to focus on, though it was sufficient. She grasped the handle, turned it, and flung the door of the writing room open.

He was there, in front of her. No more than two or three yards of possessed air separated them. Their eyes met again, and an eloquent look, common to the living and the dead worlds, passed between them. There was compassion in that look, and love. The fictions fell away, the lies were dust. In place of the boy’s manipulative smiles was a true sweetness — answered in her face.

And the dead, fearful of this look, turned their heads away. Their faces tightened, as though the skin was being stretched over the bone, their flesh darkening to a bruise, their voices becoming wistful with the anticipation of defeat. She reached to touch him, no longer having to fight against the hordes of the dead; they were falling away from their quarry on every side, like dying flies dropping from a window.

She touched him, lightly, on the face. The touch was a benediction. Tears filled his eyes, and ran down his scarified cheek, mingling with the blood.

The dead had no voices now, nor even mouths. They were lost along the highway, their malice dammed.

Plane by plane the room began to re-establish itself. The floor-boards became visible under his sobbing body, every nail, every stained plank. The windows came clearly into view — and outside the twilight street was echoing with the clamour of children. The highway had disappeared from living human sight entirely. Its travellers had turned their faces to the dark and gone away into oblivion, leaving only their signs and their talismans in the concrete world.

On the middle landing of Number 65 the smoking, blistered body of Reg Fuller was casually trodden by the travellers’ feet as they passed over the intersection. At length Fuller’s own soul came by in the throng and glanced down at the flesh he had once occupied, before the crowd pressed him on towards his judgement. Upstairs, in the darkening room, Mary Florescu knelt beside the McNeal boy and stroked his blood-plastered head. She didn’t want to leave the house for assistance until she was certain his tormentors would not come back. There was no sound now but the whine of a jet finding its way through the stratosphere to morning. Even the boy’s breathing was hushed and regular. No nimbus of light surrounded him. Every sense was in place. Sight. Sound. Touch.

Touch. She touched him now as she had never previously dared, brushing her fingertips, oh so lightly, over his body, running her fingers across the raised skin like a blind woman reading braille. There were minute words on every millimetre of his body, written in a multitude of hands. Even through the blood she could discern the meticulous way that the words had harrowed into him. She could even read, by the dimming light, an occasional phrase. It was proof beyond any doubt, and she wished, oh God how she wished, that she had not come by it. And yet, after a lifetime of waiting, here it was: the revelation of life beyond flesh, written in flesh itself.

The boy would survive, that was clear. Already the blood was drying, and the myriad wounds healing. He was healthy and strong, after all: there would be no fundamental physical damage. His beauty was gone for-ever, of course. From now on he would be an object of curiosity at best, and at worst of repugnance and horror. But she would protect him, and he would learn, in time, how to know and trust her. Their hearts were inextricably tied together.

And after a time, when the words on his body were scabs and scars, she would read him. She would trace, with infinite love and patience, the stories the dead had told on him. The tale on his abdomen, written in a fine, cursive style. The testimony in exquisite, elegant print that covered his face and scalp. The story on his back, and on his shin, on his hands. She would read them all, report them all, every last syllable that glistened and seeped beneath her adoring fingers, so that the world would know the stories that the dead tell.

He was a Book of Blood, and she his sole translator.

As darkness fell, she left off her vigil and led him, naked, into the balmy night. Here then are the stories written on the Book of Blood. Read, if it pleases you, and learn.

They are a map of that dark highway that leads out of life towards unknown destinations. Few will have to take it. Most will go peacefully along lamplit streets, ushered out of living with prayers and caresses. But for a few, a chosen few, the horrors will come, skipping to fetch them off to the highway of the damned.

So read. Read and learn.

It’s best to be prepared for the worst, after all, and wise to learn to walk before breath runs out.

THE MIDNIGHT MEAT TRAIN

LEON KAUFMAN WAS no longer new to the city. The Palace of Delights, he’d always called it, in the days of his innocence. But that was when he’d lived in Atlanta, and New York was still a kind of promised land, where anything and everything was possible.

Now Kaufman had lived three and a half months in his dream-city, and the Palace of Delights seemed less than delightful.

Was it really only a season since he stepped out of Port Authority Bus Station and looked up 42nd Street towards the Broadway intersection? So short a time to lose so many treasured illusions.

He was embarrassed now even to think of his naivety. It made him wince to remember how he had stood and announced aloud:

‘New York, I love you.’

Love? Never.

It had been at best an infatuation.

And now, after only three months living with his object of adoration, spending his days and nights in her presence, she had lost her aura of perfection. New York was just a city.

He had seen her wake in the morning like a slut, and pick murdered men from between her teeth, and suicides from the tangles of her hair. He had seen her late at night, her dirty back streets shamelessly courting depravity. He had watched her in the hot afternoon, sluggish and ugly, indifferent to the atrocities that were being committed every hour in her throttled passages.

It was no Palace of Delights.

It bred death, not pleasure.

Everyone he met had brushed with violence; it was a fact of life. It was almost chic to have known someone who had died a violent death. It was proof of living in that city.

But Kaufman had loved New York from afar for almost twenty years. He’d planned his love affair for most of his adult life. It was not easy, therefore, to shake the passion off, as though he had never felt it. There were still times, very early, before the cop-sirens began, or at twilight, when Manhattan was still a miracle.

For those moments, and for the sake of his dreams, he still gave her the benefit of the doubt, even when her behaviour was less than ladylike.

She didn’t make such forgiveness easy. In the few months that Kaufman had lived in New York her streets had been awash with spilt blood.

In fact, it was not so much the streets themselves, but the tunnels beneath those streets.

‘Subway Slaughter’ was the catch-phrase of the month. Only the previous week another three killings had been reported. The bodies had been discovered in one of the subway cars on the AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS, hacked open and partially disembowelled, as though an efficient abattoir operative had been interrupted in his work. The killings were so thoroughly professional that the police were interviewing every man on their records who had some past connection with the butchery trade. The meat-packaging plants on the water-front were being watched, the slaughter-houses scoured for clues. A swift arrest was promised, though none was made.

This recent trio of corpses was not the first to be discovered in such a state; the very day that Kaufman had arrived a story had broken in The Times that was still the talk of every morbid secretary in the office.

The story went that a German visitor, l

ost in the subway system late at night, had come across a body in a train. The victim was a well-built, attractive thirty-year-old woman from Brooklyn. She had been completely stripped. Every shred of clothing, every article of jewellery. Even the studs in her ears.

More bizarre than the stripping was the neat and systematic way in which the clothes had been folded and placed in individual plastic bags on the seat beside the corpse.

This was no irrational slasher at work. This was a highly-organized mind: a lunatic with a strong sense of tidiness.

Further, and yet more bizarre than the careful stripping of the corpse, was the outrage that had then been perpe-trated upon it. The reports claimed, though the Police Department failed to confirm this, that the body had been meticulously shaved. Every hair had been removed: from the head, from the groin, from beneath the arms; all cut and scorched back to the flesh. Even the eyebrows and eyelashes had been plucked out.

Finally, this all too naked slab had been hung by the feet from one of the holding handles set in the roof of the car, and a black plastic bucket, lined with a black plastic bag, had been placed beneath the corpse to catch the steady fall of blood from its wounds.

In that state, stripped, shaved, suspended and practically bled white, the body of Loretta Dyer had been found.

It was disgusting, it was meticulous, and it was deeply confusing.

There had been no rape, nor any sign of torture. The woman had been swiftly and efficiently dispatched as though she was a piece of meat. And the butcher was still loose.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

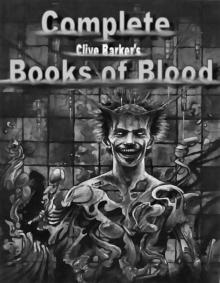

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

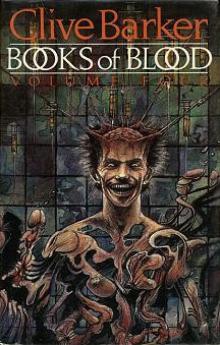

Books Of Blood Vol 4