- Home

- Clive Barker

Books of Blood Vol 5 Page 8

Books of Blood Vol 5 Read online

Page 8

'This is personal, Jerry.'

He nodded.

'I'll call the police,' she volunteered. 'You find out what's missing.'

He did as he was told, white-faced. The blow of this invasion numbed him. As he walked listlessly through the flat to survey the pandemonium - turning broken items over, pushing drawers back into place - he found himself imagining the intruders about their business, laughing as they worked through his clothes and keepsakes.

In the corner of his bedroom he found a heap of his photographs.

They had urinated on them.

'The police are on their way,' Carole told him. 'They said not to touch anything.'

Too late,' he murmured.

'What's missing?'

Nothing,' he told her. All the valuables - the stereo and video equipment, his credit cards, his few items of jewellery - were present.

Only then did he remember the ground-plan. He returned to the living-room and proceeded to root through the wreckage, but he knew damn well he wasn't going to find it.

'Garvey,' he said.

'What about him?'

'He came for the ground-plan of the Pools. Or sent someone.'

'Why?' Carole replied, looking at the chaos. 'You were going to give it to him anyway.'

Jerry shook his head. 'You were the one who warned me to stay clear -'

'I never expected something like this.'

'That makes two of us.'

The police came and went, offering faint apologies for the fact that they thought an arrest unlikely. 'There's a lot of vandalism around at the moment,' the officer said. 'There's nobody in downstairs...'

'No. They're away.'

'Last hope, I'm afraid. We're getting calls like this all the time. You're insured?'

'Yes.'

'Well, that's something.'

Throughout the interview Jerry kept silent on his suspicions, though he was repeatedly tempted to point the finger. There was little purpose in accusing Garvey at this juncture. For one, Garvey would have alibis prepared; for another, what would unsubstantiated accusations do but inflame the man's unreason further?

'What will you do?' Carole asked him, when the police picked up their shrugs and walked.

'I don't know. I can't even be certain it was Garvey. One minute he's all sweetness and light; the next this. How do I deal with a mind like that?'

'You don't. You leave it well be,' she replied. 'Do you want to stay here, or go over to my place?'

'Stay,' he said.

They made a perfunctory attempt to restore the status quo -righting the furniture that was not too crippled to stand, and clearing up the broken glass. Then they turned the slashed mattress over, located two unmutilated cushions, and went to bed.

She wanted to make love, but that reassurance, like so much of his life of late, was doomed to failure. There was no making good between the sheets what had been so badly soured out of them. His anger made him rough, and his roughness in turn angered her. She frowned beneath him, her kisses unwilling and tight. Her reluctance only spumed him on to fresh crassness.

'Stop,' she said, as he was about to enter her. 'I don't want this.'

He did; and badly. He pushed before she could further her objections.

'I said don't, Jerry.'

He shut out her voice. He was half as heavy again as she.

'Stop.'

He closed his eyes. She told him again to stop, this time with real fury, but he just thrust harder - the way she'd ask him to sometimes, when the heat was really on - beg him to, even. But now she only swore at him, and threatened, and every word she said made him more intent not to be cheated of this, though he felt nothing at this groin but fullness and discomfort, and the urge to be rid.

She began to fight, raking at his back with her nails, and pulling at his hair to unclamp his face from her neck. It passed through his head as he laboured that she would hate him for this, and on that, at least, they would be of one accord, but the thought was soon lost to sensation.

The poison passed, he rolled off her.

'Bastard...' she said.

His back stung. When he got up from the bed he left blood on the sheets. Digging through the chaos in the living room he located an unbroken bottle of whisky. The glasses, however, were all smashed, and out of absurd fastidiousness he didn't want to drink from the bottle. He squatted against the wall, his back chilled, feeling neither wretched nor proud. The front door opened, and was slammed. He waited, listening to Carole's feet on the stairs. Then tears came, though these too he felt utterly detached from. Finally, the bout dispatched, he went through into the kitchen, found a cup, and drank himself senseless out of that.

Garvey's study was an impressive room; he'd had it fashioned after that of a tax lawyer he'd known, the walls lined with books purchased by the yard, the colour of carpet and paintwork alike muted, as though by an accrual of cigar-smoke and learning. When he found sleep difficult, as he did now, he could retire to the study, sit on his leather-backed chair behind a vast desk, and dream of legitimacy. Not tonight, however; tonight his thoughts were otherwise preoccupied. Always, however much he might try to turn to another route, they went back to Leopold Road.

He remembered little of what had happened at the Pools. That in itself was distressing; he had always prided himself upon the acuteness of his memory. Indeed his recall of faces seen and favours done had ID no small measure helped him to his present power. Of the hundreds in his employ he boasted that there was not a door-keeper or a cleaner he could not address by their Christian name.

But of the events at Leopold Road, barely thirty-six hours old, he had only the vaguest recollection; of the women closing upon him, and the rope tightening around his neck; of their leading him along the lip of the pool to some chamber the vileness of which had practically snatched his senses away. What had followed his arrival there moved in his memory like those forms in the filth of the pool: obscure, but horribly distressing. There had been humiliation and horrors, hadn't there? Beyond that, he remembered nothing.

He was not a man to kowtow to such ambiguities without argument, however. If there were mysteries to be uncovered here, then he would do so, and take the consequence of revelation. His first offensive had been sending Chandaman and Fryer to turn Coloqhoun's place over. If, as he suspected, this whole enterprise was some elaborate trap devised by his enemies, then Coloqhoun was involved in its setting. No more than a front man, no doubt; certainly not the mastermind. But Garvey was satisfied that the destruction of Coloqhoun's goods and chattels would warn his masters of his intent to fight. It had born other fruit too. Chandaman had returned with the ground-plan of the Pools; they were spread on Garvey's desk now. He had traced his route through the complex time and again, hoping that his memory might be jogged. He had been disappointed.

Weary, he got up and went to the study window. The garden behind the house was vast, and severely schooled. He could see little of the immaculate borders at the moment however; the starlight barely described the world outside. All he could see was his own reflection in the polished pane.

As he focused on it, his outline seemed to waver, and he felt a loosening in his lower belly, as if something had come unknotted there. He put his hand to his abdomen. It twitched, it trembled, and for an instant he was back in the Pools, and naked, and something lumpen moved in front of his eyes. He almost yelled, but stopped himself by turning away from the window and staring at the room; at the carpets and the books and the furniture; at sober, solid reality. Even then the images refused to leave his head entirely. The coils of his innards were still jittery.

It was several minutes before he could bring himself to look back at the reflection in the window. When at last he did all trace of the vacillation had disappeared. He would countenance no more nights like this, sleepless and haunted. With the first light of dawn came the conviction that today was the day to break Mr Coloqhoun.

* * *

Jerry tried to call Carole at her

office that morning. She was repeatedly unavailable. Eventually he simply gave up trying, and turned his attentions to the Herculean task of restoring some order to the flat. He lacked the focus and the energy to do a good job however. After a futile hour, in which he seemed not to have made more than a dent in the problem, he gave up. The chaos accurately reflected his opinion of himself. Best perhaps that it be left to lie.

Just before noon, he received a call.

'Mr Coloqhoun? Mr Gerard Coloqhoun?'

'That's right.'

'My name's Fryer. I'm calling on behalf of Mr Garvey -'

'Oh?'

Was this to gloat, or threaten further mischief?

'Mr Garvey was expecting some proposals from you,' Fryer said.

'Proposals?'

'He's very enthusiastic about the Leopold Road project, Mr Coloqhoun. He feels there's substantial monies to be made.'

Jerry said nothing; this palaver confounded him.

'Mr Garvey would like another meeting, as soon as possible.'

'Yes?'

'At the Pools. There's a few architectural details he'd like to show his colleagues.'

'I see.'

'Would you be available later on today?'

'Yes. Of course.'

'Four-thirty?'

The conversation more or less ended there, leaving Jerry mystified. There had been no trace of emnity in Fryer's manner; no hint, however subtle, of bad blood between the two parties. Perhaps, as the police had suggested, the events of the previous night had been the work of anonymous vandals - the theft of the ground-plan a whim of those responsible. His depressed spirits rose. All was not lost.

He rang Carole again, buoyed up by this turn of events. This time did not take the repeated excuses of her colleagues, but insisted on. speaking to her. Finally, she picked up the phone.

'I don't want to talk to you, Jerry. Just go to hell.'

'Just hear me out -'

She slammed the receiver down before he said another word. He rang back again, immediately. When she answered, and heard his voice, she seemed baffled that he was so eager to make amends.

'Why are you even trying?' she said. 'Jesus Christ, what's the use?' He could hear the tears in her throat.

'I want you to understand how sick I feel. Let me make it right. Please let me make it right.'

She didn't reply to his appeal.

'Don't put the phone down. Please don't. I know it was unforgivable. Jesus, I know...'

Still, she kept her silence.

'Just think about it, will you? Give me a chance to put things right. Will you do that?'

Very quietly, she said: 'I don't see the use.'

'May I call you tomorrow?'

He heard her sigh.

'May I?'

'Yes. Yes.'

The line went dead.

He set out for his meeting at Leopold Road with a full three-quarters of an hour to spare, but half way to his destination the rain came on, great spots of it which defied the best efforts of his windscreen wipers. The traffic slowed; he crawled for half a mile, with only the brake-lights of the vehicle ahead visible through the deluge. The minutes ticked by, and his anxiety mounted. By the time he edged his way out of the fouled-up traffic to find another route, he was already late. There was nobody waiting on the steps of the Pools; but Garvey's powder-blue Rover was parked a little way down the road. There was no sign of the chauffeur. Jerry found a place to park on the opposite side of the road, and crossed through the rain. It was a matter of fifty yards from the door of the car to that of the Pools but by the time he reached the spot he was drenched and breathless. The door was open. Garvey had clearly manipulated the lock and slipped out of the downpour. Jerry ducked inside.

Garvey was not in the vestibule, but somebody was. A man of Jerry's height, but with half the width again. He was wearing leather gloves. His face, but for the absence of seams, might have been of the same material.

'Coloqhoun?'

'Yes.'

'Mr Garvey is waiting for you inside.'

'Who are you?'

'Chandaman,' the man replied. 'Go right in.'

There was a light at the far end of the corridor. Jerry pushed open the glass-paneled vestibule doors and walked down towards it.

Behind him, he heard the front door snap closed, and then the echoing tread of Garvey's lieutenant.

Garvey was talking with another man, shorter than Chandaman, who was holding a sizeable torch. When the pair heard Jerry approach they looked his way; their conversation abruptly ceased. Garvey offered no welcoming comment or hand, but merely said: 'About time.'

'The rain...' Jerry began, then thought better of offering a self-evident explanation.

'You'll catch your death,' the man with the torch said. Jerry immediately recognized the dulcet tones of:

'Fryer.'

'The same,' the man returned.

'Pleased to meet you.'

They shook hands, and as they did so Jerry caught sight of Garvey, who was staring at him as though in search of a second head. The man didn't say anything for what seemed like half a minute, but simply studied the growing discomfort on Jerry's face.

'I'm not a stupid man,' Garvey said, eventually.

The statement, coming out of nowhere, begged response.

'I don't even believe you're the main man in all of this,' Garvey went on. 'I'm prepared to be charitable.'

'What's this about?'

'Charitable -' Garvey repeated, '-. because I think you're out of your depth. Isn't that tight?'

Jerry just frowned.

'I think that's tight,' Fryer replied.

'I don't think you understand how much trouble you're in even now, do you?' Garvey said.

Jerry was suddenly uncomfortably aware of Chandaman standing behind him, and of his own utter vulnerability.

'But I don't think ignorance should ever be bliss,' Garvey was saying. 'I mean, even if you don't understand, that doesn't make you exempt, does it?'

'I haven't a clue what you're talking about,' Jerry protested mildly. Garvey's face, by the light of the torch, was drawn and pale; he looked in need of a holiday.

'This place,' Garvey returned. 'I'm talking about this place. The women you put in here ... for my benefit. What's it all about, Coloqhoun? That's all I want to know. What's it all about?'

Jerry shrugged lightly. Each word Garvey uttered merely perplexed him more; but the man had already told him ignorance would not be considered a legitimate excuse. Perhaps a question was the wisest reply.

'You saw women here?' he said.

Whores, more like,' Garvey responded. His breath smelt of last week's cigar ash. 'Who are you working for, Coloqhoun?'

'For myself. The deal I offered-'

'Forget your fucking deal,' Garvey said. 'I'm not interested in deals.'

'I see,' Jerry replied. 'Then I don't see any point in this conversation.' He took a half-step away from Garvey, but the man's arm shot out and caught hold of his rain-sodden coat.

'I didn't tell you to go,' Garvey said.

'I've got business

'Then it'll have to wait,' the other replied, scarcely relaxing his grip. Jerry knew that if he tried to shrug off Garvey and make a dash for the front door he'd be stopped by Chandaman before he made three paces; if, on the other hand, he didn't try to escape -

'I don't much like your sort,' Garvey said, removing his hand. 'Smart brats with an eye to the main chance. Think you're so damn clever, just because you've got a fancy accent and a silk tie. Let me tell you something -' He jabbed his finger at Jerry's throat, '- I don't give a shit about you. I just want to know who you work for. Understand?'

'I already told you-'

'Who do you work for?' Garvey insisted, punctuating each word with a fresh jab. 'Or you're going to feel very sick.'

'For Christ's sake - I'm not working for anybody. And I don't know anything about any women.'

'Don't make it worse than it already is,' Fryer advis

ed, with feigned concern.

'I'm telling the truth.'

'I think the man wants to be hurt,' Fryer said. Chandaman gave a joyless laugh. 'Is that what you want?'

'Just name some names,' Garvey said. 'Or we're going to break your legs.' The threat, unequivocal as it was, did nothing for Jerry's clarity of mind. He could think of no way out of this but to continue to insist upon his innocence. If he named some fictitious overlord the lie would be uncovered in moments, and the consequences could only be worse for the attempted deception.

'Check my credentials,' he pleaded. 'You've got the resources. Dig around. I'm not a company man, Garvey; I never have been.'

Garvey's eye left Jerry's face for a moment and moved to his shoulder. Jerry grasped the significance of the sign a heartbeat too late to prepare himself for the blow to his kidneys from the man at his back. He pitched forward, but before he could collide with Garvey, Chandaman had snatched at his collar and was throwing him against the wall. He doubled up, the pain blinding him to all other thoughts. Vaguely, he heard Garvey asking him again who his boss was. He shook his head. His skull was full of ball-bearings; they rattled between his ears.

'Jesus... Jesus...' he said, groping for some word of defence to keep another beating at bay, but he was hauled upright before any presented itself. The torch-beam was turned on him. He was ashamed of the tears that were rolling down his cheeks.

'Names,' said Garvey.

The ball-bearings rattled on.

'Again,' said Garvey, and Chandaman was moving in to give his fists further exercise. Garvey called him off as Jerry came close to passing out. The leather face withdrew.

'Stand up when I'm talking to you,' Garvey said.

Jerry attempted to oblige, but his body was less than willing to comply. It trembled, it felt fit to die.

'Stand up,' Fryer reiterated, moving between Jerry and his tormentor to prod the point home. Now, in close proximity, Jerry smelt that acidic scent Carole had caught on the stairs: it was Fryer's cologne.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

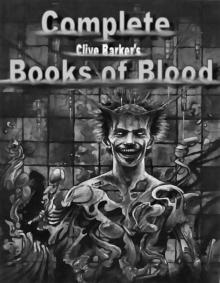

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

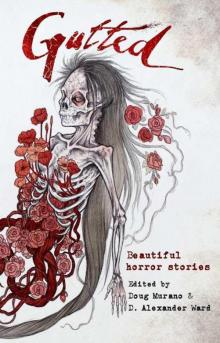

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

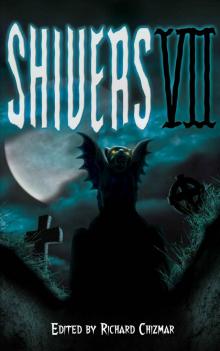

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

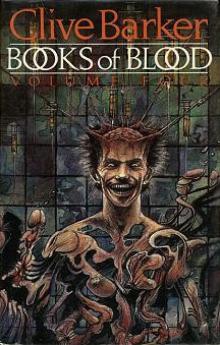

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4