- Home

- Clive Barker

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Page 6

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Read online

Page 6

Like she should confide in him, like she had a problem they could just talk through.

Beth and Kyle were standing close together in the tall grass beside the school, smoking and laughing, too far away to hear.

I just can’t believe you did that, she said.

He kicked at the dirt with his Tevas. Did what?

She was stunned.

He laughed, but it was a fake laugh, an acting-laugh. He reached for her hand.

Are you talking about last night?

What do you think I’m talking about?

What—didn’t you like it?

She pushed away, stood, walked quickly through the grass, toward Kyle and Beth. The fire behind her threw her shadow across the schoolhouse’s faded, dusty bricks.

Hey, kiddo, Kyle said.

She was angry, now. She’d never been so angry before in her life.

Beth studied her face, then held out the joint she’d been smoking. You want a hit?

Mason had followed her; he joined them, his face shadowed by the fire. Hannah took the joint and turned her back to him, then pulled the smoke in deep. Maybe, at least, her hands would stop shaking.

Easy there, Kyle said. Special blend. It’s laced with some extras.

What extras? she said.

Kyle laughed. Not sure, exactly. Got it from a chemist at Burning Man, said it was proprietary. You’re gonna feel real good, I can tell you that much.

Hannah looked at the joint, then at Beth, who smiled, kindly; she was already stoned. So was Kyle. They were no help. Nobody was going to be any help.

God. She took another hit, and then another, thinking about the way her mother put back beers, and Beth laughed.

When Hannah turned around Mason had returned to the fire, his shoulders tight, his hands in his pockets. He seemed hurt.

Good, she thought. She exhaled smoke.

II.

Imagine what it would be like to live here, Kyle said, later, the first joint gone, and a second one too. They were all sitting around the fire, wearing their headlamps in the darkness; Kyle and Beth had been talking about exploring, filling the silence left by Hannah and Mason, but no one had stood.

God, Beth said, looking at the school, I think I’d kill myself.

Hannah said nothing. Her brain was light, cottony. When she moved her head the buildings and the old light poles and Kyle and Beth and Mason—sitting by himself, sullenly, on the other side of the fire—all stretched and smeared. Kyle hadn’t lied about whatever was in that joint.

She thought about telling Beth, I know exactly what it’s like to live here.

It would be a nightmare, she could say. Wouldn’t it? To have nowhere to go and no one new to meet, and nothing to see but the endless desert and the stars in the sky. And the people you were stuck with. The people you’d chosen to follow out here.

You’d be trapped, she could say. Stuck, like the woman watching them from the street, the one in the sundress, pushing the stroller.

Hannah stood.

She’s so sad, she said, her tongue thick, and their headlamps swung to her.

Who’s sad? Beth asked.

There were several others, now. They wore long dresses and high-heeled pumps and sunhats, and they stood in bunches outside the school, and on the steps of the church, and they were walking in and out of the store holding bags, striding away down the road toward the houses, holding the hands of small children, or walking beside the men.

Beth said, hurt, God, hers kicked in fast, I barely feel anything.

She’s pretty tiny, Kyle said, and Hannah wanted to tell him, No I’m not, I’m five foot eight in heels, I’m nearly as tall as Nick—

She flushed; her forearms and cheeks and the small of her back prickled with sweat.

Mason said, Who the fuck is Nick?

Kyle—his voice odd, full of wonder—said Oh my god. Over the church.

Hannah heard them first: several pops, like gunshots, and then a crackle and sizzle—and then streams of light and smoke coming down from the sky overhead, and the boy in the stroller in front of her laughed and clapped and laughed. She might have too, except for the hand at the small of her back. His hand.

Dude, he said, what’s wrong with you?

Wow, Beth said. Wow. What’s happening here?

Hannah walked past the church, onto the street, away from Mason. Down the road, between the branches of the trees that separated one cul-de-sac from the next, Hannah saw flickering lights, golden, like flames.

The woman was walking along the sidewalk, away from her, toward the flames, pushing a stroller.

Hannah followed.

***

Then she was on the old residential streets, lined by black, grasping trees; the asphalt was shattered, sometimes upheaved into jags, elsewhere collapsed into pits and craters caked with dried mud. Her feet were numb; she had to be careful. Her whole body felt jerky, malfunctioning, like a puppet’s.

Where are you going? Mason called, behind her.

Behind them, a pop, a sizzle. The asphalt glowed a dark red, then a shuddery blue. Her shadow stretched out, wheeled, as the fireworks soared and then dropped.

The woman was walking in stride with her now along the sidewalk, in sudden, warm sunshine, smiling oddly, curiously at her; she was wearing a blue dress with a wide skirt and white flat shoes. She was Hannah’s age, or not much older—so young, and so beautiful; Hannah liked the way her dark hair curled around her ears, liked her broad hat and the smile on her face, which was soft, trusting, and Hannah felt the urge to tell her, Don’t trust anyone, before it’s too late, and before she could say this the woman stopped, and her face changed.

Jesus, Hannah, Mason said. He grabbed her wrist, the one he’d bruised. He was breathing hard.

I saw a woman.

No you didn’t—

But then he sounded doubtful.

A shape flew low overhead, big and heavy, and settled on a nearby branch. It let out a soft hoo.

The night was dark again, and colorful. Hannah turned to look behind them, and the fireworks were stuck in the sky, tendrils of light and smoke dropping in permanent, sparkling ropes behind the spire of the church. She heard laughter, applause. She heard a harsh, flat pop. Then another.

She smelled smoke, drifting low and insidious between the tree trunks.

Behind them, Beth let out a whoop, and Kyle laughed. This is amazing!

We shouldn’t be alone back here, Mason said.

Why? she asked him. She felt light, serene. What are you afraid of?

God! I’m not afraid of—

The woman was up ahead, crossing the street; she was pushing her stroller.

She pulled away from Nick’s grasp, and ran to catch up, even though this would make Nick angry, but what could she do? Everything made Nick angry. She heard him behind her, his heavy footfalls, a curse as he stumbled in the dark.

Then she was in the center of a cul-de-sac, ringed by four squat two-story bungalows. The woman was standing on the walk in front of the rightmost house, in dappled sunshine. She was wearing a different dress, white with yellow flowers and a big bell of a skirt, and next to her was Mason—no, not Mason; the man’s cheeks and eyes and beard were like Mason’s, but he had blond hair. He was wearing jeans and boots and a flannel shirt and his arm was around the woman’s shoulders. She was pregnant, Hannah saw, her stomach a taut ball. In the woman’s eyes were the reflections of fireworks, and then it was night again and lights were on through the windows of the house and the woman was standing in the doorway, looking out, at Hannah.

She retreated inside, but the door hung open behind her.

Hannah, Mason called, come back here.

Hannah forced her legs to move toward the woman’s house.

Both their headlamps were pointed at it: the rightmost bungalow, its windows boarded, its siding dark—at first Hannah wondered, Why would someone paint their house black? But then she saw: the house had burned.

That co

uldn’t be, though, because behind a picture window was a lit dining room, and the woman too—she was setting down a plate of food, smiling, in front of the blond man, but something was wrong with him, in the hunch of his shoulders, the muscles working in his jaw. Quick as a snake he caught hold of the woman’s wrist, and her eyes touched Hannah’s through the glass.

Somewhere behind them Kyle hooted, and then Mason’s arm was rough and muscled around her waist. Jesus, you’re fucked up, he said. The owl settled on a tree branch in front of the woman’s house, its eyes tracking them, yellow and translucent, like hard lemon candies.

Mason turned her, held her cheeks in between his hands. Hannah, he said.

He’d done this last night, too, after, when she’d been crying, not wanting to look him in the eyes. He’d held her head like this and kissed her.

Her body broke free from his grip and she ran toward the open door of the house, and the woman she could see inside of it, drifting back from the doorway, beautiful and kind and terrified, inviting her in.

***

The ruined door pushed gently open at her touch, and with it came sunlight; it threw her shadow ahead of her, swinging it across the room as if on a hinge.

What a lovely house! Directly ahead, narrow stairs climbed into shadow. The living room, just to her left, was already furnished. Nick had shipped out a couch and two matching armchairs and a coffee table; they were arranged neatly on the thick brown carpet. There was no television, but he’d warned her about that: he could afford one, sure, but this far out you couldn’t get a signal. To her right was the dining room; in its center was a long table and six chairs with high backs. She would have friends, she would have people over, she would entertain.

She could live in a place like this. The dining room window looked out over the cheerful cul-de-sac, and while the trees the mine had planted were only saplings, now, they’d grow in, and before long they’d provide shade, and she wouldn’t see the mountain on the horizon while cooking. This house would be like any house back in the city. And Nick was standing in the kitchen, smiling at her—but his eyes bore into her, gave her that feeling she could not put a word to, a fear and a pride and a quickening in her breath, and she went to him and he kissed her, he was grabbing at her dress, and then it was dark out and he was standing over her, and her cheek was burning, and Hannah was gasping in the cold, she’d tripped over the torn old linoleum of the kitchen floor, and her head swum and her nostrils stung with mold and soot and her breath clouded in the beam of her headlamp and outside Mason called, Hannah, what the fuck are you doing?

The woman stood on the other side of the kitchen, smiling down. She was holding a can of gasoline.

Then she drifted away, into the hallway behind her.

Hannah climbed to her feet. She crossed the kitchen. Where the woman had stood the air smelled of smoke, of the dry dust that blew up from the pages of old books.

Hannah! Mason called. He was angry, now, she could hear it; she remembered him in the tent, the fear and the pain, and her heart pounded.

She wanted to tell the woman, We can’t let him in.

The woman was entering a dark doorway, halfway down the hall.

Hannah crept to the door and looked through it after her. In the beam of her headlamp was a four-poster bed. The woman lay beneath the man, her face tilted toward the door. He was naked; thrusting; the woman’s legs were wrapped around his hips; Hannah couldn’t watch them, it made her hurt to watch them, but she did. The woman wanted her to. The woman’s cheeks were wet. The bed thumped against the wall. Her eyes, soft and deep, locked with Hannah’s.

The fireworks popped like gunshots over the church. Upstairs, wings fluttered like flames, catching and spreading.

She heard Mason say, Who’s there?

He said, Who are you?

The bed was empty, now, lit blue and cold by her headlamp. The sheets and comforter were pulled halfway down. The mattress was darkened along one side, stained wet and black in the shape of a crescent. Smoke was pooling around her ankles.

The woman was at her left, now, at the end of the hallway, where it joined the living room. Mason was in the house—the dining room, she thought. The woman had her hands on the shoulders of a young boy. His face was heartbreakingly pretty and pale and his hair was blond and he was crying—

Jesus Christ, Helen, Mason said. His voice odd. Deeper. Don’t make me come find you.

The woman had gone. Hannah crossed the living room, her feet barely touching the floor, listening, keeping herself at all times on the opposite side of the house from Mason. Now she was near the front doorway again, at the foot of the stairs. The woman stood near the top, smiling down at her.

Hannah lifted her feet, placed them, pushed down. The wooden steps had give to them; old nails groaned.

Mason said, Woman, I’m gonna stripe your ass, and Hannah didn’t know what that meant, but she did. She climbed more quickly.

His footfalls—he must be in the kitchen—were heavy, narcotic, his words slurred and too loud. Hannah pulled closer to the woman with every step, even though the air, here, was buzzing and thick with dust. Hannah gagged. And then the woman was just above her, and Hannah could not, would not, look at her face; she did not want to know what the woman really looked like—because though the woman was kind and beautiful and smiling, another face lay beneath that one; she knew, deep down, that she could not bear to see it, because she knew that the house had burned—the woman had burned it, after—she knew how all this ended, and the woman needed her to, and smoke was in the air and she smelled—

In the back hallway Mason said, Fucking Christ, Helen, tell me why I married you if you’re going to be like this. Each word sharp and full of hatred.

They were in the upstairs hallway, now. The hall was short; one door to the right, and one to the left. The woman stopped, stricken, in front of the closed right door. John was playing in there, and had angered him. John always angered him. Through the door she heard Nick shouting, she heard the boy’s cries, heard her own name being called—

Then the woman was carrying the child in her arms, through the doorway to the left.

Helen! Mason bellowed, from down below, in the living room.

Hannah followed the woman and stood in the doorway. In her headlamp’s beam was a small bed, and over the bed was a model biplane, or an owl, hanging from a thread, and behind it, in the sky, fireworks burst, and below on the bed was the boy, lying on his back atop the covers, and beside the bed knelt the woman, and Hannah joined her, gagging, and John’s face was swollen and red, blood crusting his nose and lips, and the woman stroked his hair and kissed his forehead, remembering unbidden his tiny mouth at her breast—at once gentler and more forceful than Nick’s mouth had ever been; she remembered pushing the boy through and out of her, she remembered the smell of his hair and the way his cries became a fishhook in her heart, moving her from place to place; she remembered taking him, every year, to see the fireworks; she thought that even now, like this, he looked more like his father than her, and how unjust that was, that he would have this father, this father who—

I’m gonna make you sorry you were born, Mason said, from the foot of the steps—

A man was bending over the bed; he was lifting a stethoscope from the boy’s chest.

Then he was passing his hand over the boy’s eyes, first one and then the other.

And Hannah knew, then: this was why you stayed forever, because after this, where could you ever go?

The sound that tore from Hannah’s throat was both hers and not hers; the sound had substance, a beak and feathers, and it left her, hunting.

***

She stepped from the room back into the hallway. He was thumping up the steps. Outside the fireworks boomed and sizzled and whined, and Hannah heard the people of the town clapping and cheering—the same women who’d brought her flowers and casseroles and held her hand in church, who told her, You have to endure, who told her, It’ll be all right; but

they didn’t have to be with him, they didn’t have to share a bed with him, even now, lying awake in the night thinking of the pistol he kept in the nightstand, waiting for him to fall asleep—

Not one of them wanted to see what was happening to her. What she had to endure.

She followed the woman down the hallway, as far as she could from the stairs. The woman pointed at the floor, and Hannah saw, then, the sagging, rotted floorboards in the center of the hall; she edged around them to the left, then stood with her back pressed against the charred wallpaper.

The fireworks sounded like gunshots, like her heart beating.

She could only see the light on his forehead as he reached the top of the steps. Just as he could see hers, at the end of the hall, blinding and obscuring.

His voice was clotted, at once angry and terrified.

Hannah? Is that you?

She thought of him in the tent, pressing her down.

It’s me, she said. I’m here.

He walked to her, his footsteps heavy. The floorboards cracked and broke beneath him, and he dropped away into darkness as though yanked there by a hand.

***

She descended the stairs, her palm flat against the ashy wallpaper. She could barely breathe; her throat was coated with dust and smoke.

Outside Kyle and Beth were laughing, calling for them.

She was tempted to go to them right now, to tell them there’d been an accident. But she had to see. She owed him that.

She picked a path through the living room to the rear of the house. Her feet and hands tingled, as though waking. Her headlamp revealed the charred carpet, the scars in the burned beams and exposed bracing, the rot and muck. She entered the back hallway, went to the doorway of the room with the stained bed. But the bed was gone—there was only a jumble of wood and plaster in the center of the room, and on top of it was Mason, his limbs as broken as the boards beneath him. A cut across his forehead had slicked his face with blood. In his fear he looked younger than he was. A boy, not much older than her.

The woman was kneeling beside him.

Please, he said. Don’t.

***

She was running from the house, now, toward Kyle’s and Beth’s voices; her footfalls and her body had weight again; what a relief it was to be herself again, to fill her lungs with air, and she told herself she must always remember it; the woman had given her this; it was a gift.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

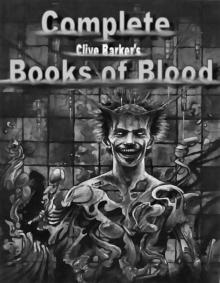

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

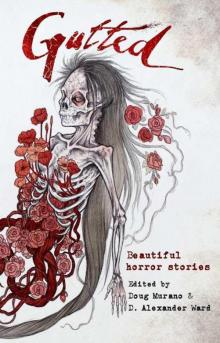

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

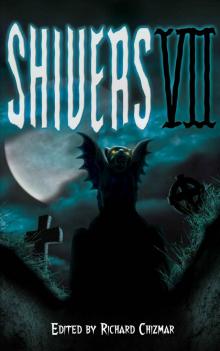

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

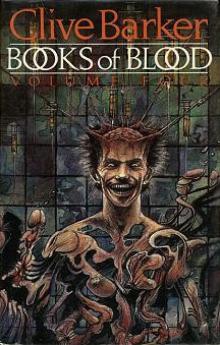

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4