- Home

- Clive Barker

Shivers 7 Page 5

Shivers 7 Read online

Page 5

“Keep on going. Drive all night, maybe. Get us another car, bigger one, then go wherever we feel like. Big country. Ain’t hardly seen much of it yet.”

It took a few seconds for his meaning to sink in. “No! No! My girl, my job….”

“They don’t matter no more. Just you and me, Jack, from now on.”

Bloodstained fingers snaked out of the blanket, closed around my knee again. The feel of them made my flesh crawl.

“We’ll have fun together,” he said. “Lots of fun.”

The Storybook Forest

Norman Prentiss

It wasn’t a girls’ ride any longer.

The giant teacups had lost their glossy white sheen, and the flowery trim had faded beneath new designs of chipped paint and cracked fiberglass. Craig aimed his flashlight over the nearest rim: dead leaves and broken branches settled into a wet muck at the bottom of the cup. The circular bench was broken in three places.

“Reading the tea leaves?” Eddie said, peering over his shoulder.

“Yeah. They tell me it’s time to trash this place.” Craig smacked the side of the cup with his palm. He expected a hollow thump, but it was firm and flat, like hitting a piece of drywall. They must have reinforced the frame with bent iron, poured concrete into the hollow fiberglass. Safer that way.

“This one’s better,” Skates yelled from the edge closest to the moonlit castle. He was climbing into one of the cups, his long legs straddling over the rim instead of using the rounded doorway opposite the teacup handle. His foot caught on the rim and he almost fell inside headfirst—not because he was drunk, yet, but because Skates was basically lanky and uncoordinated. His nickname altered his last name of Slate, and reflected his ambitions more than any success with the skateboard. He was mostly a wipe-out kind of guy.

Craig headed over, Eddie following like he usually did. Craig kicked a broken bottle out of their path, and it clanked against a pile of rusted beer cans. They obviously weren’t the first who’d trespassed into Storybook Forest for a bit of underage drinking.

Skates set his six-pack of Bud on the flat round steering wheel at the center of the cup, then put his wide-bottom flashlight next to it, letting the beam shine up like a weak spotlight. “C’mon in. Got our own coffee table.” He wrapped his T-shirt around a bottle cap, twisted it off, then took a loud swig.

The metal chain was still fastened across the doorway. Back when the park was open, vinyl padding covered the chain—white, if Craig remembered properly, sewn with pink thread to match pink roses painted on the cup. He brushed along the chain, brittle like sand beneath his fingertips, then found the hook-latch. He squeezed the release to open it, and the latch broke in his hand.

He must have cried out—startled, or maybe a sliver of rust lanced into his thumb or beneath his fingernail—because Eddie said, “Careful you don’t get tetanus.” That was Eddie, always giving advice after it was too late.

The chain clanked to the side of the cut-out doorway. Craig rubbed his thumb and forefinger together. “What is tetanus, anyway? Do you even know?”

That would quiet him for a few minutes.

The bottom wasn’t as mucked up as in the other cups, and the bench around the inside perimeter was still intact. Craig stepped over Skates’ legs and sat across from him, leaving space for Eddie. Each cup was designed to hold two parents and a couple of kids. They had plenty of room.

“Some ride,” Eddie said. He clinked his quart bottle of Colt 45 on the center wheel. Eddie never shared, never pitched in with Skates’ six-pack. His glass bottle always looked the same, with a heavily rubbed label. He probably filled the bottle with diet soda.

“This was the only ride,” Craig said. “Guy who built the place wanted a different kind of amusement park. The idea was for kids to walk through these fake little houses, as if they were Goldilocks or Hansel and Gretel or something.” Craig remembered how it pissed him off as a kid: they got to go to King’s Dominion once when he was growing up—with its dizzying Tilt-a-Whirl, water slides, and the Rebel Yell coaster that his parents wouldn’t let him ride. Maybe when you’re older, but they never went back.

Instead, his family went to Storybook Forest for a half-day every summer.

“My sister loved it here,” he said. “Hallie thought the place taught her how to read. How to love books, I guess.”

“Yuck,” Skates said, and Eddie punched him in the shoulder. “What’s that for?”

“’Cause you’re a douche.” Eddie took a sip from his Colt 45. A faint hiss like carbonation came from the bottle. He screwed the cap back on, like he always did after each sip.

Skates started laughing. Nothing was that funny, and for a moment Craig wondered if maybe he should punch the guy too. Then Skates grabbed at the steering wheel. “Oh man, how fast did this thing go? I bet you had to hold on for dear life!”

All three of them were laughing now, a kind of pre-drunk high where stupid stuff managed to hit you the right way. “God, Craig, your mom must have been terrified.”

“Stop it. You’re killing me.” Craig lifted a bottle from his half of the carton, popped it open.

“I mean, with this thing spinning and shit. It spins, right?” He held the wheel again, this time grunting.

“Put your weight into it,” Eddie said.

“Yeah, it spins. It’s gotta.” He had that same determined look on his face like when he attempted a triple Ollie or tried to jump his board over the curb. He usually failed.

“Let me.” Eddie grabbed the wheel too, and there was some confusion over clockwise or counter-clockwise, you idiot, and still nothing happened. Then Skates grunted like grinding metal, or that movie sound a pirate ship makes when the deck lurches.

The teacup didn’t spin, though. It tilted up off its saucer at a steep angle, as if some invisible giant lifted it to take a drink.

The big flashlight rattled off the wheel and onto the ground. Craig saved the carton, though he spilled his half-empty bottle in the process. He remained inside the cup, one leg balanced against the steering post. Skates had been in the end that arced into the air, and he’d kind of leaped out, arms and legs wide, and actually cleared the guardrail surrounding the entire ride—probably his most impressive aerial stunt ever, if he’d actually planned it, and if he hadn’t tripped on his ass after he landed. Wipe-out.

Eddie was outside the dip, like he’d been poured out of the cup onto the metal platform. His foot was caught under the cup’s rim.

“Careful,” he said. Craig stepped down to help him, and the shift in weight curled the rim tighter against Eddie’s ankle. Where the flashlight had fallen, its beam illuminated Eddie’s expression: he smiled and winced at the same time, his face round and white in the glow, like Tweedledum.

“Don’t think that was supposed to happen.” Skates dusted off the seat of his trousers and straddled back over the guardrail. “Somebody musta hit the reject button.”

“Quit joking around and get this offa me.” It was Eddie’s teacher voice, since he liked to imagine himself as the guy who kept everybody else in line. But how often is a teacher flat on the ground, stuck under a giant cup? In that position, it would be wise not to get bossy with the students.

Craig was used to this tone, so it didn’t bother him. The most important thing was to help his friend. Besides, they could tease him mercilessly later.

“Roll it counter-clockwise,” Tweedle-Eddie said. “To the left. My left, not yours. Toward the castle.”

Maybe it was too much clarification, like they were both stupid. Skates got called stupid often enough, and had the grades to back it up. He wasn’t that strong either, but he was tall—which sometimes gave him leverage.

Craig knelt down, pushing against the cup to roll it to the left—per teacher’s instructions—and it felt smooth, like Skates was working with him, but also like the cup was moving on its own. It may have been like guiding a planchette around a Ouija board, where the slider seems to move by magic, but maybe some

body’s fingers are pushing that thing on purpose. To make the board tell the guy something he needs to hear.

He pushed, Skates pushed near the top—leverage—and the cup didn’t so much roll to the left as it just kept tipping. Off the saucer, and over Eddie.

It sounded like a car crash. A heavy dent into the hollow metal platform, an echoing scrape against the matching saucer.

Eddie was silent.

Then, not so silent. High pitched complaints about how he landed, the rim barely missing his head, and his body cramped and curled around the steering post. Threats also, explaining what he might do to his friends once they got him out of there.

If he was really going to do those things, they’d be foolish to let him out.

Easier decided than done, anyway. When the ride had been operational, the main platform circled slowly, like a merry-go-round. There were a dozen or so cup-and-saucer compartments on the dilapidated ride, all attached to this metal platform. Their cup—the one they’d upended over their friend—had landed snug into the platform space between its vacated saucer and two other saucers. It was pinned in place at three separate points. The notched doorway had landed at an inconvenient angle, the opening mostly blocked by a saucer lip. Only a half-moon slot was visible, not big enough even for skinny Skates to limbo through. For Eddie, it was out of the question.

Skates retrieved his flashlight and shined it into the blocked opening. Eddie’s face slid into the light, a prisoner looking out from his dungeon. A cloud of breath came from his mouth like angry smoke. He blinked, then shifted back into darkness. “Done looking?”

Skates shrugged and set the flashlight on the ground. He gripped the lid of the opening and tested it. “Heavier than I thought. Help me, Craig.”

They couldn’t lift it, and couldn’t shift the cup to clear the opening. Eddie’s fingers suddenly appeared in the opening, an extra pair of hands that for some reason Craig hadn’t been expecting. They didn’t help.

“We need something,” Skates finally said, out of breath. “A crowbar or a log or something.”

Craig shouted into the dark opening. “You’ll be all right here?” As if Eddie had a choice.

“Leave me a flashlight.”

“Mine’s broken,” Craig said. “We need the other one for searching and stuff.”

Eddie sighed. He mentioned calling an ambulance or the police, then at once realized how stupid the idea was. What a humiliation it would be, caught trespassing in a kiddie park, and trapped under an upended, paint-flecked, fiberglass teacup.

Skates patted the side of the cup. “We won’t be long.”

“You better not be.”

* * *

Trouble was, the place really was a forest. Suburban property was plentiful when park designers conceived the idea for Storybook Forest, so they spread their attractions over a large area. Little kids would walk along park paths, discovering one presumably magical attraction after another. Hallie used to run from Jack Spratt’s pumpkin house to find the giant shoe around the next corner. Dad would read the placard for her, until she learned how to read it herself: “There was an old woman who lived in a shoe. She had so many children, she didn’t know what to do.”

So Craig and Skates had a lot of ground to cover—especially since they didn’t exactly know what they were looking for.

They found the house for the three little pigs. Not a brick one, which would be too much like an ordinary house, but the one made of straw. A fiberglass wolf used to huff and puff outside the door; his feet remained, legs snapped off at the ankles, and a few other broken pieces stomped into the ground. Once upon a time, the straw was simulated with bright yellow paint, brown now and making it more like a house of wet, dirty rope. The place seemed menacing in a way unintended in the park’s heyday. It was smaller than a real house. Instead of sharp corners, the angles were rounded and out of alignment—a whimsical effect on sunny days when the house was fresh, but now it looked as if the place was melting. The windows were smashed. Craig imagined innocent children reaching across the empty frames, their soft wrists tearing over jagged glass.

The windows were too small to climb through. Craig shined a light inside, revealing plump, upright pigs that had been target practice for beer bottles. Ears and snouts were broken off, little pig hooves shattered into sharp claws. Judging from the smell, they’d also been pissed on.

If vandals could have stepped inside, the pigs would likely have been torn to pieces, like the wolf.

“Chinny chin chin,” Skates said. He pushed his finger against the tip of his nose, turning it into a snout.

“Let’s try another house.” They followed the curve of the cracked blacktop path. Signposts had long-since disappeared, but a few joined shadows in the clearing identified the route: these were silhouettes of the remaining gingerbread children, baked to death in the witch’s oven. The doomed children always seemed blissfully happy, hands linked and dancing in a circle. Mom and Dad bought cookies from the snack booth, and Craig and his sister sat at a bench beside the victim circle, biting off cookie arms and legs, and not at all feeling like cannibals.

“Long past its expiration date,” Skates said. The house itself had grown horribly unappetizing. Giant gumdrop trim looked moldy, and gingerbread shingles were stale and drizzled with grime. The ice cream chimney was cracked down the side of the cone; a vanilla dip at the top was brown and lumpy, like a huge scoop of vomited oatmeal.

Inside was a single room, a large metal cauldron at the center and overflowing with garbage.

“Look at her feet!” Skates pointed and laughed at the brick oven. The witch’s legs were painted dangling at the back of the open oven, presumably because Hansel and Gretel had just pushed her inside. “And check out the cage.” A sign beside a grid of iron bars said, Next Victims. Skates laughed some more.

And that was what was wrong with Storybook Forest. It made you laugh. Happy little stories for happy little kids. There was no lock on the cage. You could climb inside, wrap your tiny hands around the metal bars, and know all along you’d never get cooked by the witch.

Craig hated the treachery of it all. The smiling storybook world where nothing bad ever happened. “They sanitized all the stories. I wanted stuff to be scary, like the thrill-rides at King’s Dominion, and it always disappointed me.”

Skates pulled at one of the metal bars. It didn’t budge from its concrete moorings.

“You know,” Craig said, “the real versions of the nursery stories are pretty gruesome. The wolf eats Little Red Riding Hood’s grandma—the woodsman has to carve her out of his stomach. And Cinderella wasn’t like the Disney cartoon. The stepsisters cut off parts of their feet so the glass slipper would fit.”

“That’s kinda cool.”

“I dragged us here tonight—pushed for it, even, when Eddie tried to talk us out of it—because I thought for once the forest actually might be scary. We’d break in late at night, and the place would be falling apart and maybe dangerous. Haunted. But it’s not. It’s just sad.”

“I bet Eddie’s pretty scared right now. He probably crapped himself when that cup fell on him.”

Craig wouldn’t laugh with him. “You didn’t do that on purpose, did you?”

“No. Did you?”

“I mean, you said you didn’t realize how heavy it was.”

“I said no.” Skates attempted a serious expression, but it still came across like a smirk. He got in trouble for that a lot at school.

“All right,” Craig said. “Let’s keep looking around.”

* * *

Outside, Craig cupped his hands over his mouth and yelled into the air. “We’re still here. We’ll get you out soon.”

No answer. Might have been too far away, and the sound didn’t carry well. Just as likely, Eddie was giving them the silent treatment.

Skates did a two-fingered whistle, then made a few hoot-owl noises.

“Cut it out,” Craig said. “He’s probably sulking.”

&n

bsp; Still no signposts, but he registered where they were headed. In the midst of the overgrown forest a giant shoe loomed, a front door carved out of its heel. He remembered the windows in the sides and up the tall back of the shoe—like a tower, the old woman leaning out the top window to wave at her many children, some of them scrambling over bright blue laces, and she’d waved at him and Hallie, too.

She still waved, but she was headless. The filthy shoe looked like something a homeless giant had worn through, then discarded.

The door was open, but when Skates ducked inside he couldn’t get far. Craig pushed in after him. A spiral staircase had fallen over, along with all the upstairs exhibits. A few small body parts were visible: several of the old woman’s children had been crushed in the collapsing rubble.

Skates pulled at a plank that looked intact. It broke at his touch. The wood was rotten.

Craig recalled Hallie’s sing-song recitation of the rhyme—so many children she didn’t know what to do. How many children were there, really?

“This is a terrible rhyme,” he told Skates.

“Dude, it’s a lame-ass park all around.”

“That not what I mean. The rhyme—I think it’s about being poor. This woman’s got all these kids, and she’s freaking old, and doesn’t have a husband or a job. They’re living in a shoe, for Christ’s sake. Real life, they’d be starving to death.”

Skates kicked at another board. A tiny fiberglass hand holding a lollipop rolled off the pile. “What a shithole.”

“Hallie actually cried when they closed this place down. But I guess she cried about a lot of things.”

“Can’t compete with that, can you?”

“Nope. Hallie always got her way.”

“I’m sorry man.”

“That’s okay.” Craig closed his eyes for a second, blacking out the flashlight beam and the trash and the pile of collapsed rubble. Everything but the memories. “I wish I’d never come here.”

“We’ll be out soon enough,” Skates said. He set the flashlight on the floor, planted one foot at the bottom of the heap, and grunted and pulled at a curled metal bar. It was part of the broken banister, about five feet long once he’d extracted it. “This’ll work like a big crowbar, don’t you think?”

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

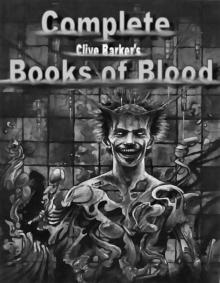

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

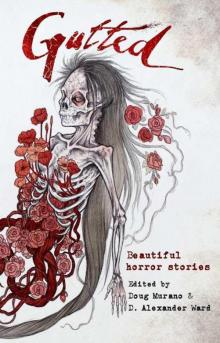

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

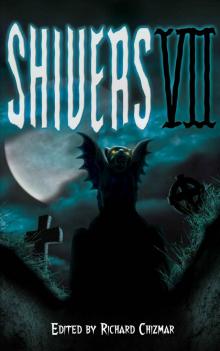

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

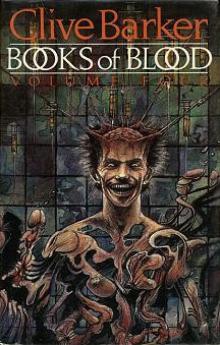

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4