- Home

- Clive Barker

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Page 4

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Read online

Page 4

“Everyone—except Kasia.”

“Yes, everyone except my mother,” I agreed.

“You’re seventeen on the 17th,” Ludi said. “That’s really something special. And we’re going to celebrate.”

“What? How?” I kept thinking about how in general, those of us working in the hospital infirmary lived a little better, but still, I’d lost so much weight I had no breasts to speak of. For at least two or three years I’d looked forward to wearing a bra and now I was fifteen and had the nubbins you’d see on a ten-year old child. I’d had one period—my first—back in June, but like most women in the camp, my menses had dried up. My mother said they put something in the food—she didn’t know what—and that was why the only pregnant women were the ones that had just arrived on the damn indefatigable trains. I don’t know—maybe it was just from being starved—but even if I’d complained back then about the cramps and the low-grade headache, about the messy red napkins and the elastic sanitary belt, even though I griped like my girl cousins and school friends, I’d been secretly pleased when I got my period. Like being admitted to some exclusive club you longed—ached—to get into. But, that had been taken from me, too.

“Up ’til then, even though she said she had Doctor Viktor Freisler wrapped around her little finger, Ludi hadn’t been able to convince me to ‘organize’ the supply room. Oh, I knew she was taking things here and there—bandages, ointments for trench foot—that kind of thing. But she was crafty and she didn’t have to rely on stealing from just the infirmary. She had ‘Canada,’ too. You could buy off an SS-Totenkopfverbände—a young German guard—for a half-pint of schnapps, or a kiss . . .

“It was about a week before my birthday and Ludi said, ‘You’ve been eating a little better and now that you look a little better, Gia’—she called me that, a nickname for Eligia and I’d never had any nickname before—‘and Rudi’—Rudi was one of her swains, ‘Rudi has a friend named Frederic, and he would like to spend a little time with you . . . ’”

I knew who Frederic was. He had blond hair and green eyes, a grin like my father’s. If he weren’t German—if he were Polish—I’d have had a hopeless crush on him. Still, he was very good looking, and Ludi said he was nice.

“Take your time,” Stella Johansson, said. She could see I was struggling to get this out; she didn’t even glance at the thin bracelet watch on her wrist to check how long I’d been talking. She was very pretty; even the weak, intermittent late April sun brought out the golden highlights in her soft brown upswept hair. She was so much like Ludi, I thought maybe I could tell her everything. Tell her how, without meaning to, I betrayed my mother for a pair of red high-heeled shoes. Red shoes . . .

Red shoes . . . and a broken tooth.

Stella Johansson was so pretty, I thought she’d understand better—more clearly—if I explained about my father and Ruta and my mother. Surely, as a good-looking grown-up woman, she knew the significance—the importance—of physical appearance. “When my father disappeared, there was a postcard,” I said.

“Yes,” she said, nodding. “That was such a low trick the Nazis played. Giving those early prisoners postcards making them say all was well and that inmates could receive packages. The SS got more goods for the Reich, they got addresses of others who would, in turn, become prisoners. They falsely assured those not yet rounded up that things were not so bad in the camps. All lies . . . and more subterfuge . . . ”

Stella was right about the postcards, but the one written in my father’s hasty scribble also said “I have seen Ruta in the women’s camp.” I never understood why he’d tell my mother that he’d seen the woman he left her for in 1939. Maybe he mixed up the cards and meant to send that one to his brother or a close friend—maybe it was a Nazi prank after they’d beaten out of him the names of his colleagues, the details of his life.

All I knew was they’d been arguing for a year or more. He told my mother that she was sad and angry all the time. She was no fun, she’d let herself get unkempt, sloppy—niechlujny! he kept shouting at her in Polish. The other nurses at the hospital worked just as hard and they looked all right. Ruta worked with him in the operating room and she looked fine. Ruta liked laughing, liked a bit of fun. “The war is going to kill us all,” he yelled. He was packing his suitcase. “And I mean to have a little joy, a little beauty! Before the Nazis kill us all, I’m going to have just one summer rose. Tylkojeden zanim umrę!” Just one before I die!

I was angry at her. If she’d just fix herself up, I said over and over, maybe my father would come back. Instead, two years later there was the postcard from Dachau: I have seen Ruta!

“I don’t know what your situation was during the war,” I said to the clerk, “but surely it’s a human desire to look your best. A human right—a God-given right.” I seemed to notice for the first time there was a tiny diamond ring winking on the third finger of her left hand. “My mother had her chance—but she said it was more important to live—to work: therefore to live—good looks would take care of themselves when there was time that belonged to us again.”

“What happened, Eligia?”

She’s so pretty, I thought. Whatever she may have suffered during the war, she’s attractive again. Desirable. She’s engaged. Happy . . .

But could I really tell her? Tell her that Ludi and I stole three quarter-grain morphine tablets to be exchanged in “Canada” for a certain pair of real Parisian red high-heeled shoes to be worn on a special date in three days’ time? That the shoes were safely hidden and I was in a fever of excitement when I broke my tooth the morning of my birthday? Should I tell this kindly Red Cross clerk, whose life was apparently so tidy? Should I tell her . . .

We—Ludi and I—were in the supply room, my confidence was shattered. I had one of the dental mirrors and I was trying to smile so that the broken tooth—the little dog tooth on the lower left—wouldn’t show. “Is it very bad? I’m so embarrassed. That lousy bread! If only I’d had a toothbrush or vitamin C tablets—it never would have happened!”

“You can get it fixed later, Gia—the war is almost over. I’m going to dress you up to the nines tonight—lipstick and everything!”

My head was swimming. A real date. One of Ludi’s dresses. High heels—from Paris!

“Let’s take two more of the tablets—you have one, give the other to Frederic—he’ll think you’re a movie star and you’ll be feeling no pain—that’s a guarantee!”

As I watched her, she shook out three tablets.

“But, you said two—”

There was a fierce rattling sound and the door was flung open.

Standing there, with the angriest look on her face I’d ever seen was my mother.

“What happened, Eligia?” Stella Johansson said again. “Why did we find you—like the female kapos and the SS guards who were forced by the Americans—carrying the dead and flinging them into the mass graves?”

It was a punishment detail, I knew—the guards were made to understand what they’d done all during the war and then just before liberation. Running away, leaving thousands to starve, leaving the dead unburied . . . the Americans rounded them up and brought them back.

“What happened? Do you remember?”

But I could not tell her that I stayed mute when Ludi turned my mother in, told the doctor my mother (a nurse! a healer!) had been saving other mothers by stilling the lives of their newborn babies. I could not tell her that just two days before the camp was liberated, I saw my mother’s face there among the heaps of bodies no one had cleared from the gas chambers . . . .The frenzied attempt by the Nazis to disguise the horrors of what they’d done all those long years. A final solution. I could not tell her that I knew the war was essentially over, that we’d be free soon, but that I kept quiet to wear red heels and lipstick for my birthday date with the young German who would soon no longer be my enemy. I could not tell her that. I could not tell her I was afraid I’d be beaten—or worse—for speaking up. I could not tell her, that

I’d realized—too late—that atonement never makes up for the guilt we suffer, for the sins we have committed. I couldn’t tell her that nothing is ever enough to make up for the sin of silence, but we have to try.

Pretty as she was, I didn’t think she’d understand—really understand—what I felt when I looked at the mounds of thousands of the dead, lifted their sagging bodies, inhaled the terrible stench from the pits . . . those beaten, starved, shot, and gassed human scarecrows. She’d never understand, because I didn’t understand it myself. I saw my mother’s face, head turned, her mouth in a rictus, her body lying on its side near the gas chamber door. Her work was done.

“Why Eligia?” she asked again. Above us, the sun disappeared behind sudden clouds.

“I helped bury the dead . . . because . . . it was the human thing to do,” I said, “and I know that from my nurses training, from my work in the hospital.”

Arbeit Macht Frei.

Work can set you free.

THE PROBLEM OF SUSAN

Neil Gaiman

She has the dream again that night.

In the dream, she is standing, with her brothers and her sister, on the edge of the battlefield. It is summer, and the grass is a peculiarly vivid shade of green: a wholesome green, like a cricket pitch or the welcoming slope of the South Downs as you make your way north from the coast. There are bodies on the grass. None of the bodies are human; she can see a centaur, its throat slit, on the grass near her. The horse half of it is a vivid chestnut. Its human skin is nut-brown from the sun. She finds herself staring at the horse’s penis, wondering about centaurs mating, imagines being kissed by that bearded face. Her eyes flick to the cut throat, and the sticky red-black pool that surrounds it, and she shivers.

Flies buzz about the corpses.

The wildflowers tangle in the grass. They bloomed yesterday for the first time in . . . how long? A hundred years? A thousand? A hundred thousand? She does not know.

All this was snow, she thinks, as she looks at the battlefield.

Yesterday, all this was snow. Always winter, and never Christmas.

Her sister tugs her hand, and points. On the brow of the green hill they stand, deep in conversation. The lion is golden, his arms folded behind his back. The witch is dressed all in white. Right now she is shouting at the lion, who is simply listening. The children cannot make out any of their words, not her cold anger, nor the lion’s thrum-deep replies. The witch’s hair is black and shiny, her lips are red.

In her dream she notices these things.

They will finish their conversation soon, the lion and the witch . . .

There are things about herself that the professor despises. Her smell, for example. She smells like her grandmother smelled, like old women smell, and for this she cannot forgive herself, so on waking she bathes in scented water and, naked and towel-dried, dabs several drops of Chanel toilet water beneath her arms and on her neck. It is, she believes, her sole extravagance.

Today she dresses in her dark brown dress suit. She thinks of these as her interview clothes, as opposed to her lecture clothes or her knocking-about-the-house clothes. Now she is in retirement, she wears her knocking-about-the-house clothes more and more. She puts on lipstick.

After breakfast, she washes a milk bottle, places it at her back door. She discovers that the next-door’s cat has deposited a mouse head and a paw, on the doormat. It looks as though the mouse is swimming through the coconut matting, as though most of it is submerged. She purses her lips, then she folds her copy of yesterday’s Daily Telegraph, and she folds and flips the mouse head and the paw into the newspaper, never touching them with her hands.

Today’s Daily Telegraph is waiting for her in the hall, along with several letters, which she inspects, without opening any of them, then places on the desk in her tiny study. Since her retirement she visits her study only to write. Now she walks into the kitchen and seats herself at the old oak table. Her reading glasses hang about her neck on a silver chain, and she perches them on her nose and begins with the obituaries.

She does not actually expect to encounter anyone she knows there, but the world is small, and she observes that, perhaps with cruel humor, the obituarists have run a photograph of Peter Burrell-Gunn as he was in the early 1950s, and not at all as he was the last time the professor had seen him, at a Literary Monthly Christmas party several years before, all gouty and beaky and trembling, and reminding her of nothing so much as a caricature of an owl. In the photograph, he is very beautiful. He looks wild, and noble.

She had spent an evening once kissing him in a summer house: she remembers that very clearly, although she cannot remember for the life of her in which garden the summer house had belonged.

It was, she decides, Charles and Nadia Reid’s house in the country. Which meant that it was before Nadia ran away with that Scottish artist, and Charles took the professor with him to Spain, although she was certainly not a professor then. This was many years before people commonly went to Spain for their holidays; it was an exotic and dangerous place in those days. He asked her to marry him, too, and she is no longer certain why she said no, or even if she had entirely said no. He was a pleasant-enough young man, and he took what was left of her virginity on a blanket on a Spanish beach, on a warm spring night. She was twenty years old, and had thought herself so old . . .

The doorbell chimes, and she puts down the paper, and makes her way to the front door, and opens it.

Her first thought is how young the girl looks.

Her first thought is how old the woman looks. “Professor Hastings?” she says. “I’m Greta Campion. I’m doing the profile on you. For the Literary Chronicle.”

The older woman stares at her for a moment, vulnerable and ancient, then she smiles. It’s a friendly smile, and Greta warms to her.

“Come in, dear,” says the professor. “We’ll be in the sitting room.”

“I brought you this,” says Greta. “I baked it myself.” She takes the cake tin from her bag, hoping its contents hadn’t disintegrated en route. “It’s a chocolate cake. I read on-line that you liked them.”

The old woman nods and blinks. “I do,” she says. “How kind. This way.”

Greta follows her into a comfortable room, is shown to her armchair, and told, firmly, not to move. The professor bustles off and returns with a tray, on which are teacups and saucers, a teapot, a plate of chocolate biscuits, and Greta’s chocolate cake.

Tea is poured, and Greta exclaims over the professor’s brooch, and then she pulls out her notebook and pen, and a copy of the professor’s last book, A Quest for Meanings in Children’s Fiction, the copy bristling with Post-it notes and scraps of paper. They talk about the early chapters, in which the hypothesis is set forth that there was originally no distinct branch of fiction that was only intended for children, until the Victorian notions of the purity and sanctity of childhood demanded that fiction for children be made . . .

“Well, pure,” says the professor.

“And sanctified?” asks Greta, with a smile.

“And sanctimonious,” corrects the old woman. “It is difficult to read The Water Babies without wincing.”

And then she talks about ways that artists used to draw children—as adults, only smaller, without considering the child’s proportions—and how the Grimms’ stories were collected for adults and, when the Grimms realized the books were being read in the nursery, were bowdlerized to make them more appropriate. She talks of Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” and of its original coda in which the Prince’s cannibal ogre mother attempts to frame the Sleeping Beauty for having eaten her own children, and all the while Greta nods and takes notes, and nervously tries to contribute enough to the conversation that the professor will feel that it is a conversation or at least an interview, not a lecture.

“Where,” asks Greta, “do you feel your interest in children’s fiction came from?”

The professor shakes her head. “Where do any of our intere

sts come from? Where does your interest in children’s books come from?”

Greta says, “They always seemed the books that were most important to me. The ones that mattered. When I was a kid, and when I grew. I was like Dahl’s Matilda. . . . Were your family great readers?”

“Not really. . . . I say that, it was a long time ago that they died. Were killed. I should say.”

“All your family died at the same time? Was this in the war?”

“No, dear. We were evacuees, in the war. This was in a train crash, several years after. I was not there.”

“Just like in Lewis’s Narnia books,” says Greta, and immediately feels like a fool, and an insensitive fool. “I’m sorry. That was a terrible thing to say, wasn’t it?”

“Was it, dear?”

Greta can feel herself blushing, and she says, “It’s just I remember that sequence so vividly. In The Last Battle. Where you learn there was a train crash on the way back to school, and everyone was killed. Except for Susan, of course.”

The professor says, “More tea, dear?” and Greta knows that she should leave the subject, but she says, “You know, that used to make me so angry.”

“What did, dear?”

“Susan. All the other kids go off to Paradise, and Susan can’t go. She’s no longer a friend of Narnia because she’s too fond of lipsticks and nylons and invitations to parties. I even talked to my English teacher about it, about the problem of Susan, when I was twelve.”

She’ll leave the subject now, talk about the role of children’s fiction in creating the belief systems we adopt as adults, but the professor says, “And tell me, dear, what did your teacher say?”

“She said that even though Susan had refused Paradise then, she still had time while she lived to repent.”

“Repent what?”

“Not believing, I suppose. And the sin of Eve.”

The professor cuts herself a slice of chocolate cake. She seems to be remembering. And then she says, “I doubt there was much opportunity for nylons and lipsticks after her family was killed. There certainly wasn’t for me. A little money—less than one might imagine—from her parents’ estate, to lodge and feed her. No luxuries . . . ”

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

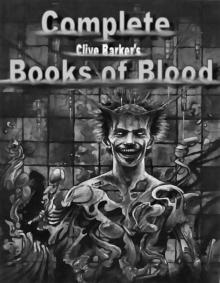

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

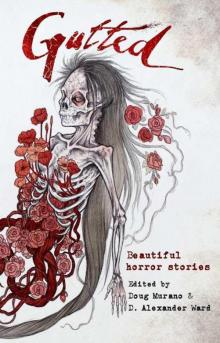

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

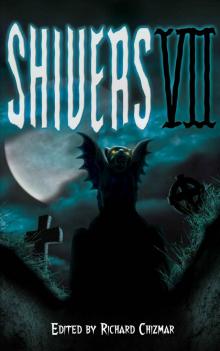

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

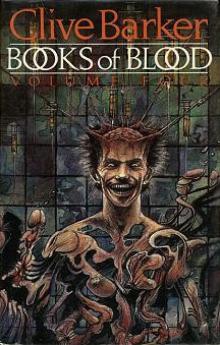

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4