- Home

- Clive Barker

Tonight, Again Page 4

Tonight, Again Read online

Page 4

“I asked you a question,” he said. “Do you understand me?”

She looked at him and nodded.

“I’m sick of your complaining and sour faces. And I want no more of it.”

That was an end to the exchange. There were others, no doubt, not that night but other nights, when her father lost his temper with her, but she doesn’t remember them. She remembers only this one, on the night she first felt the fire.

Is she crazy now? Perhaps, though she doesn’t feel crazy. When she looks around at other people in the world she sees insanity. For her own part, she feels quite sane.

She approaches the home. It’s night; the glow of the fire is thrown up against the walls of the house. She sits in the yard. The fire flows from her. When it flows too far, she calls it back to her, and it comes, like a child. That, in a sense, is what she’s come to show her father: his grandchild. Perhaps, yes, the spectacle will horrify him, but so be it. He is dying, she has heard. If he doesn’t see his grandchild now, then he’ll never see it.

She goes in, and up the stairs. People recognize her and hurry away. Did they know that she was coming? She knows what they say behind their hands: Poor Mad Martha; the lunatic woman.

He is lying in his bed, attended by a doctor. She knows the man by sight; she’s seen him on the street.

“Be quick,” he tells Martha. “Say your goodbyes and leave.”

“I want to be alone with him.”

The doctor concedes to this. He leaves her with her father.

“Can you hear me?” she says to the old man.

“Yes…”

“Here…” she says. And she brings the fire up out of her groin to show him. It is a terrible moment. She sees the horror on his face: the terror, even, that she has brought this thing here, under his roof.

“Get out!” he says.

The fire gets bigger. She starts to coax it back towards her, but she didn’t expect to be so confounded by her father’s presence, and it gets away from her. It leaps up towards the ceiling, and forms a fantastic fiery vault over his bed. He stares up at it—his face lit from the blaze—in terror, like a man caught beneath a piece of toppling masonry, certain he’ll be crushed.

He cries out; the fire starts to fall towards the bed. She makes a great effort to call it to her, and it comes. “I’m sorry,” she stammers, “I’m sorry—”

The doctor has entered. What has he seen? Something, surely.

His gaze goes past her to the bed; she looks his way, and to her horror discovers that her father is gasping, like a fish, shiny bubbles of blood spilling from his nose. The doctor pushes her aside. He calls for help.

She doesn’t wait. She starts down the darkened stairs, listening to the chaos going on above. Her father’s terrible gasping. The doctor shouting orders.

As she gets to the ninth stair (the stair with the creak) she feels the fire erupt in her again. She lets out a terrible sob. It rises around her, so vast and so powerful it carries her out into the night.

Just before dawn, with body laid out, and all that can be done for the night, done; the doctor gone; the stars gone; Martha’s brother Frederick, who was the only one who ever laughed with her, goes to the window. He has drunk two glasses of brandy since his father’s death; he is light-headed. And tired with the effort of thinking of what will happen now; now that the old man’s dead. His eyes surely betray him. That can’t be Martha he sees, coming into the yard, hanging under a fiery form, like something that came out of the heart of a furnace. Yes it is. It is. Her body is bluish and cold, her mouth utters a sad sound. She is joined with the creature, at the hip. It is a lewd sight. The creature brings her close to the house. She looks up at her brother, in the window. Then, with that same piteous expression on her face, she allows her captor, or her consort, to carry her away. Frederick goes down into the yard. The vision has disappeared. Nor is there any sign of it having passed this way. No scorch marks on the ground. No smell of burning. Nothing a material man might agree was evidence of it having been here. He is pleased to believe he was deluded and returns into the safety of the house until daylight.

Tit

I have a preoccupation--it almost amounts to a fixation—with the breast, in both sexes. I could write at length about the nuances of the breast: its variations, its complexities; its heft. I am amused by it; yes, even in the singular, as the needs of language require that I describe it here. I have enjoyed the particular beauty of women who have lost one of their breasts to accident or to surgery. The mascetomodee, if there is such a word: She is a glory unto herself.

The breast of the virgin, small and budding: this is beautiful. The breast of the mother, filled with milk; this is surpassingly beautiful. The breast of the woman given over to pleasure, who spends great periods of time at her toilet bathing her bosom, pondering it, rouging the nipples; this is a joy, of course. The breast of the whore, which is likely bruised a little, marked by the teeth of over-excited customers; a spectacle, no question. And then, after the menopause, where the breast passes its ripeness, but gains heft, perhaps, or starts to sink back against the body, this is quite lovely too. It is no longer functional, in the strictest sense. It must be rediscovered; adorned, teased, made new as an object of tender veneration.

Finally, the purse. In old age, the breast as a ghost. This is my favorite form, because it is the most neglected. I have kissed such sacs for hours on end, tugging on the nipples like a suckling, as though I might with sufficient teasing, call forth a stream of old maid’s milk.

The Freaks

He imagines himself amongst the freaks. He imagines himself their willing prisoner, his normality, in such company, visible. They mock him. They make him go naked so as to laugh at the symmetry of his limbs, at the straightness of his back, at his very ordinariness.

They are not mundane. Though they are made of flesh and blood, though the hair on the chin of the woman who leads them is coarse, and the stink of the donkey-man like a blow, they partake, these people, of the condition of angels. They are rare. They come with messages from another place.

That’s why he likes to be with them. To let them use him, to let them mock him. He feels, in their company, as though the miraculous is pressing against him.

Cruelty

I knew an ardent Communist once

(a theatre director, actually;

back in the days before the Wall fell,

and the only way to be employed

in certain quarters

was to be to the Left of Lenin)

who could only achieve

any kind of sexual arousal

when beneath the heels

of a mock-Fräulein

dressed in something Nazified.

Sometimes nature is even crueler than politics.

Dollie

Ellie was fifteen that year, and it was the unhappiest year of her life. Her mother had died in the early spring, worn out by having too many babies, and loving them; by hard work, by the hopelessness of everything. The sky here was so big, and the dirt so dark, and though sometimes there were kind warm rains out of that sky, and sometimes the dirt gave up a little crop of potatoes, life was as hard for the family as life could be.

Towards the end, Ellie’s mother had started to talk about how life had been back in Virginia, before they came out West. How fine the people were, and how gentle the air. Ellie didn’t remember much of this. She’d been a tiny baby when they’d left. All she knew was Wisconsin: the bitter, bitter winters, the wasting summers. She knew how to write, a little; read, a little; but not enough to understand the family Bible, which was the only book in the house. There was nothing else to occupy her mind. Her only plaything was a wooden doll, which her father had made on her sixth birthday. Over the years she’d lost the crude features that her father had painted on her little head; she was just a naked shape.

After her mother’s death, Ellie's life became even harder for Ellie. She had to keep house in her mother’s stead, co

oking for her brothers and her two younger sisters and her father, doing her best to make what little food could be grown or hunted to feed six hungry mouths. She was neither happy nor sad most of the time. She had no expectation for her life.

One day, her father said: “That doll of yours. Get rid of it.”

“Why, Papa?”

“You’re not a child anymore. Get rid of it.”

She feared her father when he was cross, so she did as she was instructed. She told him she’d put the doll in the fire, but this was not the truth. She went down to the river, to a little strand of old oaks where she’d played as a child, and she hid Dollie in a hole between the roots.

The next year, there was a man from Boston called Jack Matthews, who asked to marry her. She didn’t like him very much, but it was a chance to get away from the house, and maybe begin a better life.

She married Jack Matthews in the summer, and he took her back east. Barely a week passed before she began to see a side of him he’d hidden from her. He didn’t want a wife, he wanted a servant, and when she didn’t jump to it fast enough for him, he became violent. She wasn’t a weeper; she took his abuse in silence, and only shed a tear when his back was turned. In bed, he was virtually useless, for which he also blamed her, finding further reason for violence. But what was she to do? There was nobody to turn to for help. She had no money of her own, and she was very far from home. And even supposing she’d upped and left, to try and make her way back to Wisconsin: what awaited her there if she made it? More days of dirt and sky? Better, she thought, to endure her husband. Perhaps he’d mellow as the years went on. Perhaps she’d even learn to love him a little.

But life didn’t get any better. They went from town to town, and he’d get a job for a while, she’d do some laundering, and there’d be a few weeks of calm. Then things, for one reason or another, would start to fall apart. He’d get in a fight and be fired, or they’d have to move on because he owed somebody money after a night of gambling. Sometimes she wanted to kill him. She even thought of ways to do it, while she laundered. A pillow over his face while he was in a drunken stupor; or poison in his coffee. Would God blame her so much if she ridded the world of Jack Matthews? Surely not. But the plans never came to anything. However much she hated him—and she hated him to her marrow—she couldn’t bring herself to kill him.

The only pleasure in her life came from an unlikely source. She often laundered the bed-linen that came out of whore houses (which was the lowliest form of a lowly profession), and through her coming and going to these disreputable places, she got to know some of the women. Though she had neither the looks nor the confidence to do what they did, she had much in common with them, not least a deep contempt for the opposite sex. Many, like her, had seen life out in the wilderness, and had fled from it. And most would not have cared to return to the life they’d left. To be sure, whoring was no great pleasure to them, but even a modest bordello provided its little luxuries—clean linen, perfume soap, sometimes a fancy gown—which they would never have had out on the frontier.

She learned to laugh with these women: she learned to voice her rage at the stupidity of men. She learned a great deal else, besides, that she would have blushed to admit. She had never known, for instance, that often women pleasured themselves (and sometimes one another); nor that there were devices made for such pleasurings. Toys made of polished wood shaped like a man’s sex, but more reliably hard. One of the women she met had quite a little collection of these things, including one carved from the tusk of an elephant, which she said was the best, because it was so silky smooth. One night, she offered to show Ellie how she used it to best effect, and Ellie sat and watched while the woman gave her what would turn out to be the most important lesson of her life.

Two years went by. The nomadic life continued for Ellie and Jack, a by now predictable pattern of arrival, hard labour, violence and quick departure. As her husband’s state of mind slowly deteriorated, thanks to drink and innumerable beatings, his abuse of Ellie escalated. But—though the women she knew advised countless times to part from Jack before he killed her—Ellie couldn’t bring herself to leave him. He was pathetic, yes; but he was all she had in the world.

Then, one night, after Jack had been particularly brutal, she had a strange dream. She was back in Wisconsin, standing on the doorstep of the cabin, and she heard a voice calling to her. It was a sweet, familiar voice, but it was neither that of a man or a woman. She went out looking for whoever it was who was calling her, and the journey led her down to the river. Now, as she walked beneath the ancient trees that drooped their summer boughs towards the water, she knew who was calling her. Her dream-self knelt down beneath the oldest of the oaks, and she dug between the roots. There in the dark earth was Dollie. As her fingertips grazed the familiar form, she heard, somewhere close by, the sound of somebody gasping for breath. It was a horrid, desperate sound. She glanced back over her shoulder for a moment but she could see nothing, so she returned to the business of unearthing Dollie. But the choking sound got louder and louder, and she began to feel some force buffeting her.

“Let me alone!” she said.

The din just grew worse, the buffeting stronger. The dream began to recede. Dollie fell out of her fingers, back into the ground.

And suddenly she was awake, and the bed was shaking, and Jack was jerking around, with his hands to his throat. She got up out of bed. It was just about dawn. There was enough light to see his agony: the way his body thrashed, and his eyes starting from their sockets in terror. There were flecks of spittle around his mouth, and a dark patch at his groin where he’d voided himself.

She did nothing. He seemed to see her there, watching him in this terrible state, but she wasn’t sure. The seizure, or whatever it was, had such a grip on him that eventually it threw him off the bed, and he died there, on the floor before her, with the stink of his bowels and bladder rising from him.

She took virtually nothing with her. She just left, without saying a word to anyone. Who was she going to tell? And who would care anyway? Perhaps God had had some use for her husband: but if so, then He was the only one.

It took her seven weeks to get to Wisconsin, and almost every night she heard Dollie’s voice in her dreams. Had she not done so, she would not have gone.

When she got back she found the cabin deserted. There was still some furniture, but the few possessions the family had owned—a kettle, some pots and pans, a broom, and so on—had gone. She slept on the floor that night, and the next day went around the neighbourhood to find out what had happened to everyone. They’d moved away to Oregon, she was told, about three months before. Nobody had an address, of course, because the travellers hadn’t known where they were going. She never saw any of them again; or even heard news of them.

Folks were kind to her. They supplied her with the bare essentials so that she could get settled back into the cabin, and that’s what she did. A few people said she could come and live in town, but she didn’t want that. She’d live alone, she said, and see how it suited her.

As it turned out, it suited her very well. She got herself a job at the feed store in town, and that made her enough money to fix up the cabin, and put food on the table.

For company she had Dollie. She’d gone down to the river the day after she arrived, and her doll was there, where she’d hidden her years before. A little damp from being hidden in the earth, of course, but she dried out quite nicely. One night, sitting by the window watching the sun go down, a queer little thought came into her head. The next day she bought a whittling knife in town and set about refashioning Dollie so that her company might be more pleasurable. She didn’t hurry; this was a job she wanted to do just right. Off came the arms and the legs; off came the ears, and all but a tiny nub of nose. The body she thinned out a little, but not too much. A sense of fullness was important, her friend the whore had instructed. She put some little furrows here and there, just to add some spice to the sensation. Then, sitting pea

cefully in a rocking chair (which had been her only concession to luxury) she hoisted up her skirts, and had a little party with Dollie. It was perfectly grand.

She lived to be eighty-nine, and never had any other person, man or woman, under her roof for company, right to the end. Nor, she would have said, needed any.

The Collection

When did I start collecting? Oh, now you’re asking. Truth is, I can’t remember a time when I didn’t have a few photographs of the male appendage. Ha! Funny the number of words there are for it. I remember reading somewhere there were more words for a man’s wotzit than for any other thing on the face of the earth. I don’t know where I read it. But I remember thinking, well I’m really in on something important, with my collection.

Yes. Yes you’d think something so private would be…well, private. Ha. Yah. Private. Yeah. But…that’s the paradoxical thing. They’re called privates but they’re not. I bet that thing about the number of words is true about photographs too. Oh, I know you’d think the likeliest subject for a photograph would be…I don’t know, a sunset. But, no. It’s the old appendage, isn’t it? No question. It stands to reason. Ha. Daft thing to say. Stands to reason. But the fact is you got a lot of men with, you know, more or less average appendages, still think of them like it’s their favorite child, you know? And they want to have a record of what it looked like when it stood up, you know, perfectly straight, with one eye on Heaven. Because we all see that there’ll be a time when that don’t happen any more. When it doesn’t snap to attention. When it just hangs there, even if it was a really big one. Come to think of it, especially if it was a really big one. So I’ve never had to—what’s the word?—coerce any one of my owners. Not a one. No, nor paid so much as a shilling to take a photograph.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

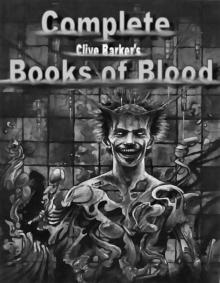

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

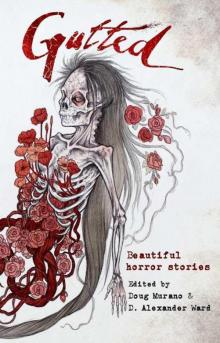

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

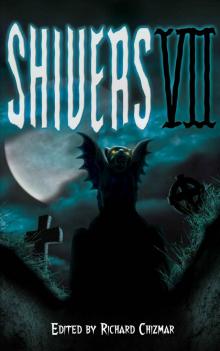

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

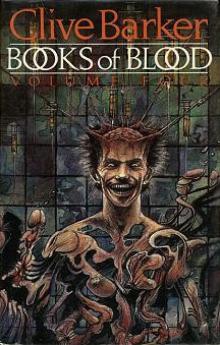

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4