- Home

- Clive Barker

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Page 4

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Read online

Page 4

She glanced back over her shoulder down the length of Lincoln Street. From here it was a half-hour walk home, at least. If the great gilded cloud was bringing rain, then she was going to get wet on her way back to Followell Street. But she had no desire to start the homeward trek, not for a little while, at least. She had no idea of what lay ahead of her besides the wild hills and the long grass, and the orange milkweed, the larkspur, and prairie lilies in among the grass.

But walking for a while where nobody (except the Widow White) knew she’d gone was better than going home to listen to her father in the first stages of the day’s drinking, raging on about the injustices of his life.

Without another thought she walked on past the STREET ENDS sign, catching it with her palm as she went so that it rocked in the shallow hole some lazy workman had made for it, and headed out into the gently swaying grass.

Butterflies and bees wove ahead of her, as if they were showing her the way. She followed them, happily. When next she looked back, the shoulder-high grass had almost obscured Chickentown from sight. She didn’t care. She had a good sense of direction. When the time came for her to find her way back, she’d be able to do just that. Her eyes glued to the great swelling mass of the cloud, she walked on, her griefs and humiliations left somewhere behind her, where the road ended and the ocean of grass and flowers began.

5. A Shore Without a Sea

After perhaps ten minutes of walking, Candy glanced back over her shoulder to see that the gentle swells and gullies she’d crossed to get to her present position had put Chickentown out of sight completely. Even the spire on the church on Hawthorne Street and the five stories of the town hall had vanished.

She took a moment and turned on the spot, three hundred and sixty degrees. In every direction the landscape presented the same unremarkable vista of wind-blown grass, with two exceptions. Some way off to her right lay a small copse of trees, and nearly dead ahead of her was a much more curious sight: a kind of skeletal tower, set in the middle of this wilderness of grass and flowers.

What was it? Some kind of watchtower? If it had been a watchtower then those who’d occupied it must have been very bored, with nothing to watch.

Though it promised to be nothing more than a near ruin, she decided to make it her destination. She’d get there, sit for a while, and then head back. She was getting thirsty, for one thing. She wanted a glass of water. Maybe on the return journey she’d pick up some soda from Niles’ Drug Store. She dug in her pocket, just to see what she had. Two singles, one five- and one ten-dollar bill. She pushed them down to the very bottom of her pocket, so they wouldn’t slip out.

The wind had become stronger in the time since she’d left the limits of Chickentown, and a little more bracing. There was still the smell of spring green in the air, but there was something else besides, something Candy couldn’t quite name, but which teased her nevertheless.

She walked toward the tower, her mind becoming pleasantly devoid of troubling thoughts. Miss Schwartz; letters threatening expulsion; her father in his drinking chair, staring up at her with that look of his, the look she knew meant trouble: all of it was left behind, where the street ended.

Then her toe caught some object so that it skipped ahead of her through the grass. Just a stone, surely. Nevertheless, she bent down to take a closer look, and to her surprise she saw that it was not a stone at all, but a shell. It was large too: about the size of her balled fist, and there were a number of short spikes on it. It wasn’t, she knew, a snail’s shell. For one thing it was too big, and she had never seen a snail’s shell with spikes. No, this was a sea shell, and it was clearly old. Its colors had faded, but she could still see an elaborate pattern upon it: a design that followed its diminishing spiral.

She turned it over, brushed what looked suspiciously like sand out of its crevice, and put it to her ear. It was a trick her grandfather had first taught her, listening to the sea in a shell. And though she knew it was just an illusion—the subtle reverberations of the air in the shell’s interior—she was still half persuaded by it; half certain she heard the sound of waves, as if the shell still had some memory of its life in the ocean.

She listened. There it was.

But what was a seashell doing out here?

Had somebody dropped it while walking here? That seemed highly unlikely. Who went walking with seashells in their pocket?

She looked down, wondering if anything else had been dropped in the vicinity. To her surprise, the answer was yes: there were a number of odd items scattered under her feet. More shells, for one thing, dozens of them. No, hundreds; some small, a few even larger than the one she’d picked up. Most were cracked or broken, but some were still intact, their shapes and designs more beautiful, more bizarre, than anything she’d ever seen in a book.

And there was more besides, a lot more. As she studied the ground, her eyes becoming accustomed to picking out curiosities, the curiosities multiplied. There were pieces of wood scattered among the shells, most smoothed into little abstract sculptures by the pale, freckled sand that was mingled with the dark Minnesota dirt. As she bent to pick one of the sculptures up, she saw that there was glass here too: countless fragments—green, blue and white—turned into smoky jewels. She picked up three or four and examined them in the palm of her hand, walking a little way as she did so.

There were more mysteries underfoot with every step she took. A large fish—its flesh pecked away by birds, and the remains baked by the sun. And even a piece of pottery, on which a fragment of an exquisite design remained: a blue figure staring at her with almost hypnotic intensity.

Fascinated by all this, she paused to examine her finds more closely. As she did so, she caught a movement in the long grass out of the corner of her eye. She dropped down onto her haunches, below the level of the tallest grass stalks, and there she stayed, suddenly and unaccountably nervous.

She brushed the last of the sand off her fingers and watched for whatever had moved to move again.

A hard gust of wind came through the grass, making it hiss as the stalks rubbed against one another.

After perhaps a minute, during which the only motion was the bending of the grass, she decided to chance standing up.

As she did so the thing she’d seen moving chose precisely the same moment to also stand upright, so that the pair of them, Candy and the stranger, rose like two swimmers emerging from a shallow sea.

Candy let out a yelp of shock at the sight of the stranger. And then, once the shock had worn off, she started to laugh. The man—whoever he was—was wearing some kind of Halloween mask, or so it seemed. What other explanation could there be for his freakish appearance? His left eye was round and wild, while his right was narrow and sly, and his mouth, framed by a black mustache and beard, was downturned in misery.

But none of this was as odd as what sprouted from the top of his head. There were large downy ears, and above them two enormous antlers, which would have resembled those of a stag except that there were seven heads (four on the left horn, three on the right) growing from them. Heads with eyes, noses and mouths.

They weren’t, she realized now, static, nor were they made of rubber and papier-mache. In short, it was not a mask the man was wearing. These heads sprouting from the antlers were alive, and they were all staring at Candy the way their owner was staring at her: eight pairs of eyes all studying her with the same manic intensity.

She was speechless. But they were not. After a moment of silence the heads erupted into wild chatter, their manner highly agitated. Candy had no doubt about the subject of conversation. One minute the heads were looking at her, then they were facing one another, their volume rising as they attempted to out-talk one another.

The only mouth that wasn’t moving was that of the man himself. He simply studied Candy, his wild and sly expression slowly becoming one of tentative enquiry.

Finally, he decided to approach her. Candy let out a little gasp of fear, and in response he raised his lo

ng-fingered hands as though to keep her from running away. The heads, meanwhile, were still chattering to one another.

“Be quiet!” he ordered them. “You’re frightening the lady!”

All but one of the heads (the middle of the two on his right horn, a round-faced, sour individual) responded to his order. But this one kept talking.

“Keep your distance from her, John Mischief,” the head advised its big brother. “She may look harmless, but you can’t trust them. Any of them.”

“I said hush up, John Serpent,” the man said. “And I mean it.”

The head made a face and muttered something under its breath. But it finally stopped talking.

“What’s your name?” John Mischief asked Candy.

“Me?” Candy said, as though there was anybody else in the vicinity to whom the question might be directed.

“Oh Lordy Lou!” another of the heads remarked. “Yes, you, girl.”

“Be polite, John Sallow,” John Mischief said, reaching up (without taking his eyes off Candy) and lightly slapping the short-tempered head for its offense.

Then, having hushed his companion, John Mischief said: “I do apologize for my brother, lady.”

Then—of all things—he bowed to her.

It was not a deep bow. But there was something about the simple courtesy of the gesture that completely won Candy over. So what if John Mischief had seven extra heads; he’d bowed to her and called her lady. Nobody had ever done that to her before.

She smiled with improbable delight.

And the impish man called John Mischief, along with five of his seven siblings, smiled back.

“Please,” he said. “I don’t wish to alarm you, lady. Believe me, that is the very last thing I wish to do. But there is somebody in this vicinity by the name of Shape.”

“Mendelson Shape,” the smallest of the heads said.

“As John Moot says: Mendelson Shape.”

Before Candy could deal with any more information she needed a question answered. So she asked it.

“Are you all called John?” she said.

“Oh yes,” said Mischief. “Tell her, brothers, left to right. Tell her what we are called.”

So they did.

“John Fillet.”

“John Sallow.”

“John Moot.”

“John Drowze.”

“John Pluckitt.”

“John Serpent.”

“John Slop.”

“And I’m the head brother,” the eighth wonder replied. “John Mischief.”

“Yes, I heard that part. I’m Candy Quackenbush.”

“I am extremely pleased to make your acquaintance,” John Mischief said.

He sounded completely sincere in this, and with good reason. To judge by his appearance, things had not gone well for him—or them—of late.

Mischief’s striped blue shirt was full of holes and there were stains on his loosely knotted tie, which were either food or blood; she guessed the latter. Then there was his smell. He was less than sweet, to say the least. His shirt clung to his chest, soaked with pungent sweat.

“Have you been running from this man Shape?” Candy said.

“She’s observant,” John Pluckitt said appreciatively. “I like that. And young, which is good. She can help us, Mischief.”

“Either that or she can get us in even deeper trouble,” said John Serpent.

“We’re as deep as we can get,” John Slop observed. “I say we trust the girl, Mischief. We’ve got absolutely nothing to lose.”

“What are they all talking about?” Candy asked Mischief.

“Besides me.”

“The harbor,” he replied.

“What harbor?” Candy said. “There’s no harbor here. This is Minnesota. We’re hundreds of miles from the ocean. No, thousands.”

“Perhaps we’re thousands of miles from any ocean you are familiar with, lady,” said John Fillet, with a gap-toothed smile. “But there are oceans and oceans. Seas and seas.”

“What on earth is he talking about?” Candy asked Mischief.

John Mischief pointed toward the tower that stood sixty or seventy yards from where they stood.

“That, lady, is a lighthouse,” he said.

“No,” said Candy, with a smile. The idea was preposterous. “Why would anybody—”

“Look at it,” said John Drowze. “It is a lighthouse.”

Candy studied the odd tower again.

Yes, she could see that indeed it could have been designed as a lighthouse. There were the rotted remains of a staircase, spiraling up the middle of it, leading to a room at the top, which might have housed a lamp. But so what?

“Somebody was crazy,” she remarked.

“Why?” said John Slop.

“Oh, come on,” said Candy. “We’ve been through this. We’re in Minnesota. There is no sea in—”

Candy stopped mid-sentence. Mischief had put his hand to his mouth, hushing her.

As he did so all of his brothers looked off in one direction or another. A few were sniffing the air, others tasting it on their lips. Whatever they did and wherever they looked, they all came to the same conclusion, and together they murmured two words.

“Shape’s here,” they said.

6. The Lady Ascends

Mischief instantly grabbed Candy’s arm and pulled her down into the long grass. His eyes were neither wild nor sly now. They were simply afraid. His brothers, meanwhile, were peering over the top of the grass in every direction, and now and then exchanging their own fearful looks. It was most peculiar for Candy to be with one person, and yet be in the company of a small crowd.

“Lady,” Mischief said, very softly, “I wonder if you would dare something for me?”

“Dare?”

“I would quite understand if you preferred not. This isn’t your battle. But perhaps Providence put you here for a reason.”

“Go on,” Candy said.

Given how unhappy and purposeless she’d been feeling in the last few hours (no, not hours: months, even years), she was happy to listen to anybody with a theory about why she was here.

“If I could distract Mendelson Shape’s attention away from you for long enough, maybe you could get to the lighthouse, and climb the stairs? You carry far less weight than I, and the stairs may support you better.”

“What for?”

“What do you mean: what for?”

“Well, once I’ve climbed the stairs—”

“She wants to know what she does next,” John Slop said.

“That’s simple enough, lady,” said John Fillet.

“When you get to the top,” said John Pluckitt, “you must light the light!’

Candy glanced up at the ruined tower: at the spiraling spire of its staircase, and the rotting boards of its upper floor. She couldn’t imagine the place was in working order, not in its present state.

“Doesn’t it need electricity?” she said. “I mean, I can’t even see a lamp.”

“There’s one up there, we swear,” said John Moot. “Please trust us. We may be desperate, but we’re not stupid. We wouldn’t send you on a suicide mission.”

“So how do I make this lamp work?” Candy asked. “Is there an on-off switch?”

“You’ll know how to use it the moment you set eyes on it,” Mischief said. “Light’s the oldest game in the world.”

She looked at them, her gaze going from face to face. They looked so frightened, so exhausted. “Please, lady,” said Mischief. “You’re our only chance now.”

“Just one more question—” Candy said.

“No time,” said Drowze. “I see Shape.”

“Where?” said Fillet, turning to follow his brother’s gaze. He didn’t need any further direction. He simply said. “Oh Lordy Lou, there he is.”

Candy raised her head six inches and looked in the same direction that Fillet and Drowze were looking. The rest of the brothers—Mischief included—followed that stare.

And there, no more than a stone’s throw from the spot where Candy and the brothers were crouched in the grass, was the object of their fear: Mendelson Shape.

The sight of him made Candy shudder. He was twice the height of Mischief, and there was something spiderish about his grotesque anatomy. His almost fleshless limbs were so long, she could readily imagine him walking up a wall. On his back there was a curious arrangement of cruciform rods that almost looked like four swords which had been fused to his bony body. He was naked but for a pair of striped shorts, and he walked with a pronounced limp. But there was nothing frail about him. Despite the lack of muscle, and that limp of his, he looked like a creature born to do harm. His expression was joyless and sour, filled with hatred toward the world.

Having got herself a glimpse of him, Candy ducked down quickly, before Shape’s wrathful gaze came her way.

Curiously, it was only now, seeing this second freakish creature, that she wondered if perhaps she wasn’t having some kind of hallucination. How could such beings be here in the world with her?

The same world as Chickentown, as Miss Schwartz and Deborah Hackbarth?

“Before we go any further,” she said to the brothers, “I need an answer to something.”

“Ask away,” said John Swallow.

“Am I dreaming this?”

By way of reply, all eight brothers shook their heads, their faces for once expressing the same thing. No, this is no dream, those faces said.

Nor, deep in her bones, had she expected the answer to be any different. They were all awake together, she and the brothers, and all in terrible jeopardy.

Mischief saw the sequence of thoughts crossing her face. The doubt that she was even awake, and then the fear that indeed she was.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

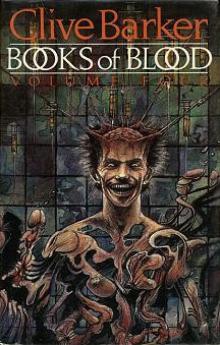

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

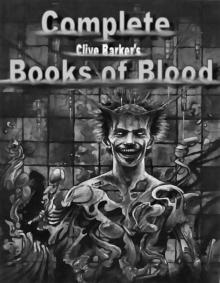

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

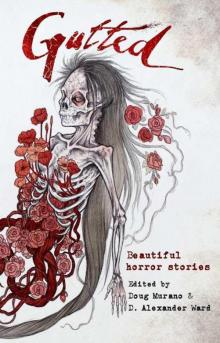

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

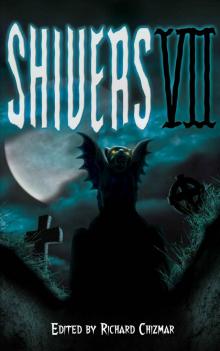

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4