- Home

- Clive Barker

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Page 2

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Read online

Page 2

"What is this?" Dowd demanded of his confessee.

"Out of me! Out of me!"

"Is this the taint?" He went down on his haunches beside her. "Is it?"

"Drive it out of me!" Quaisoir sobbed, and began assaulting her poor body afresh.

Jude could endure it no longer. Allowing her sister to die blissfully in the arms of a surrogate divinity was one thing. This self-mutilation was quite another. She broke her vow of silence.

"Stop her," she said.

Dowd looked up from his study, drawing his thumb across his throat to hush her. But it was too late. Despite her own commotion, Quaisoir had heard her sister speak. Her thrashings slowed, and her blind head turned in Jude's direction.

"Who's there?" she demanded.

There was naked fury on Dowd's face, but he hushed her softly. She would not be placated, however.

"Who's with you, Lord?" she asked him.

With his reply he made an error that unknitted the whole fiction. He lied to her.

"There's nobody," he said.

"I heard a woman's voice. Who's there?"

"I told you," Dowd insisted. "Nobody." He put his hand upon her face. "Now calm yourself. We're alone."

"No, we're not."

"Do you doubt me, child?" Dowd replied, his voice, after the harshness of his last interrogations, modulating with this question, so that he sounded almost wounded by her lack of faith. Quaisoir's reply was to silently take his hand from her face, seizing it tightly in her blue, blood-speckled fingers.

"That's better," he said.

Quaisoir ran her fingers over his palm. Then she said, "No scars."

"There'll always be scars," Dowd said, lavishing his best pontifical manner upon her. But he'd missed the point of her remark.

"There are no scars on your hand," she said.

He retrieved it from her grasp. "Believe in me," he said.

"No," she replied. "You're not the Man of Sorrows." The joy had gone from her voice. It was thick, almost threatening. "You can't save me," she said, suddenly flailing wildly to drive the pretender from her. "Where's my Savior? I want my Savior!"

"He isn't here," Jude told her. "He never was."

Quaisoir turned in Jude's direction. "Who are you?" she said. "I know your voice from somewhere."

"Keep your mouth shut," Dowd said, stabbing his finger in Jude's direction. "Or so help me you'll taste the mites—"

"Don't be afraid of him," Quaisoir said.

"She knows better than that," Dowd replied. "She's seen what I can do."

Eager for some excuse to speak, so that Quaisoir could hear more of the voice she knew but couldn't yet name, Jude spoke up in support of Dowd's conceit.

"What he says is right," she told Quaisoir. "He can hurt us both, badly. He's not the Man of Sorrows, sister."

Whether it was the repetition of words Quaisoir had herself used several times—Man of Sorrows—or the fact that Jude had called her sister, or both, the woman's sightless face slackened, the bafflement going out of it. She lifted herself from the ground.

"What's your name?" she murmured. "Tell me your name."

"She's nothing," Dowd said, echoing Quaisoir's own description of herself minutes earlier. "She's a dead woman." He made a move in Jude's direction. "You understand so little," he said. "And I've forgiven you a lot for that. But I can't indulge you any longer. You've spoiled a fine game. I don't want you spoiling any more."

He put his left hand, its forefinger extended, to his lips.

"I don't have many mites left," he said, "so one will have to do. A slow unraveling. But even a shadow like you can be undone."

"I'm a shadow now, am I?" Jude said to him. "I thought we were the same, you and I? Remember that speech?"

"That was in another life, lovey," Dowd said. "It's different here. You could do me harm here. So I'm afraid it's going to have to be thank you and good night."

She started to back away from him, wondering as she did so how much distance she would have to put between them to be out of range of his wretched mites. He watched her retreat with pity on his face.

"No good, lovey," he said. "I know these streets like the back of my hand."

She ignored his condescension and took another backward step, her eye fixed on his mouth where the mites nested, but aware that Quaisoir had risen and was standing no more than a yard from her defender.

"Sister?" the woman said.

Dowd glanced around, distracted from Jude long enough for her to take to her heels. He let out a shout as she fled, and the blind woman lunged towards the sound, grabbing his arm and neck and dragging him towards her. The noise she made as she did so was like nothing Jude had heard from human lips, and she envied it: a cry to shatter bones like glass and shake color from the air. She was glad not to be closer, or it might have brought her to her knees.

She looked back once, in time to see Dowd spit the lethal mite at Quaisoir's empty sockets, and prayed her sister had better defenses against its harm than the man who'd emptied them. Whether or no, she could do little to help. Better to run while she had the chance, so that at least one of them survived the cataclysm.

She turned the first corner she came to, and kept turning corners thereafter, to put as many decisions between herself and her pursuer. No doubt Dowd's boast was true; he did indeed know these streets, where he claimed he'd once triumphed, like his own hand. It followed that the sooner she was out of them, and into terrain unfamiliar to them both, the more chance she had of losing him. Until then, she had to be swift and as nearly invisible as she could make herself. Like the shadow Dowd had dubbed her: darkness in a deeper dark, flitting and fleeting; seen and gone.

But her body didn't want to oblige. It was weary, beset with aches and shudders. Twin fires had been set in her chest, one in each lung. Invisible hounds ripped her heels bloody. She didn't allow herself to slow her pace, however, until she'd left the streets of playhouses and brothels behind her and was delivered into a place that might have stood as a set for a Pluthero Quexos tragedy: a circle a hundred yards wide, bounded by a high wall of sleek, black stone. The fires that burned here didn't rage uncontrolled, as they did in so many other parts of the city, but flickered from the tops of the walls in their dozens; tiny white flames, like night-lights, illuminating the inclined pavement that led down to an opening in the center of the circle. She could only guess at its function. An entrance into the city's secret underworld, perhaps, or a well? There were flowers everywhere, most of the petals shed and gone to rot, slickening the pavement beneath her feet as she approached the hole, obliging her to tread with care. The suspicion grew that if this was a well, its water was poisoned with the dead. Obituaries were scrawled on the pavement—names, dates, messages, even crude illustrations—their numbers increasing the closer to the edge she came. Some had even been inscribed on the inner wall of the well, by mourners brave or broken-hearted enough to dare the drop.

Though the hole exercised the same fascination as a cliff edge, inviting her to peer into its depths, she refused its petitions and halted a yard or two from the lip. There was a sickly smell out of the place, though it wasn't strong. Either the well had not been used of late, or else its occupants lay a very long way down.

Her curiosity satisfied, she looked around to choose the best route out. There were no less than eight exits—nine, including the well—and she went first to the avenue that lay opposite the one she'd come in by. It was dark and smoky, and she might have taken it had there not been signs that it was blocked by rubble some way down its length. She went to the next, and it too was blocked, fires flickering between fallen timbers. She was going to the third door when she heard Dowd's voice. She turned. He was standing on the far side of the well, with his head slightly cocked and a put—upon expression on his face, like a parent who'd caught up with a truant child.

"Didn't I tell you?" he said. "I know these streets." "I heard you."

"It isn't so bad that you came here," he said, wa

ndering towards her. "It saves me a mite."

"Why do you want to hurt me?" she said. "I might ask you the same question," he said. "You do, don't you? You'd love to see me hurt. You'd be even happier if you could do the hurting personally. Admit it!" "I admit it."

"There. Don't I make a good confessor after all? And that's just the beginning. You've got some secrets in you I didn't even know you had." He raised his hand and described a circle as he spoke. "I begin to see the perfection of all this. Things coming round, coming round, back to the place where it all began. That is: to her. Or to you; it doesn't matter, really. You're the same."

"Twins?" Jude said. "Is that it?"

"Nothing so trite, lovey. Nothing so natural. I insulted you, calling you a shadow. You're more miraculous than that. You're—" He stopped. "Well, wait. This isn't strictly fair. Here's me telling you what I know and getting nothing from you."

"I don't know anything," Jude said. "I wish I did."

Dowd stooped and picked up a blossom, one of the few underfoot that was still intact. "But whatever Quaisoir knows you also know," he said. "At least about how it all came apart."

"How what came apart?"

"The Reconciliation. You were there. Oh, yes, I know you think you're just an innocent bystander, but there's nobody in this, nobody, who's innocent. Not Estabrook, not Godolphin, not Gentle or his mystif. They've all got confessions as long as their arms."

"Even you?" she asked him.

"Ah, well, with me it's different." He sighed, sniffing at the flower. "I'm an actor chappie. I fake my raptures. I'd like to change the world, but I end up as entertainment. Whereas all you lovers"—he spoke the word contemptuously—"who couldn't give a fuck about the world as long as you're feeling passionate, you're the ones who make the cities burn and the nations tumble. You're the engines in the tragedy, and most of the time you don't even know it. So what's an actor chappie to do, if he wants to be taken seriously? I'll tell you. He has to learn to fake his feelings so well he'll be allowed off the stage and into the real world. It's taken me a lot of rehearsal to get where I am, believe me. I started small, you know; very small. Messenger. Spear-carrier. I once pimped for the Unbeheld, but it was just a one-night stand. Then 1 was back serving lovers—"

"Like Oscar."

"Like Oscar."

"You hated him, didn't you?"

"No, I was simply bored, with him and his whole family. He was so like his father, and his father's father, and so on, all the way back to crazy Joshua. I became impatient. I knew things would come around eventually, and I'd have my moment, but I got so tired of waiting, and once in a while I let it show."

"And you plotted."

"But of course. I wanted to hurry things along, towards the moment of my ... emancipation. It was all very calculated. But that's me, you see? I'm an artist with the soul of an accountant."

"Did you hire Pie to kill me?"

"Not knowingly," Dowd said. "I set some wheels in motion, but I never imagined they'd carry us all so far. I didn't even know the mystif was alive. But as things went on, I began to see how inevitable all this was. First Pie's appearance. Then your meeting Godolphin, and your falling for each other. It was all bound to happen. It was what you were born to do, after all. Do you miss him, by the way? Tell the truth."

"I've scarcely thought about him," she replied, surprised by the truth of this.

"Out of sight, out of mind, eh? Ah, I'm so glad I can't feel love. The misery of it. The sheer, unadulterated misery." He mused a moment, then said, "This is so much like the first time, you know. Lovers yearning, worlds trembling. Of course last time I was merely a spear-carrier. This time I intend to be the prince."

"What do you mean, I was born to fall for Godolphin? I don't even remember being born."

"I think it's time you did," Dowd said, tossing away the flower as he approached her. "Though these rites of passage are never very easy, lovey, so brace yourself. At least you've picked a good spot. We can dangle our feet over the edge while we talk about how you came into the world."

"Oh, no," she said. "I'm not going near that hole."

"You think I want to kill you?" he said. "I don't. I just want you to unburden yourself of a few memories. That's not asking too much, is it? Be fair. I've given you a glimpse of what's in my heart. Now show me yours." He took hold of her wrist "I won't take no for an answer," he said, and drew her to the edge of the well.

She'd not ventured this close before, and its proximity was vertiginous. Though she cursed him for having the strength to drag her here, she was glad he had her in a tight hold.

"Do you want to sit?" he said. She shook her head. "As you like," he went on. "There's more chance of your falling, but it's your decision. You've become a very self-willed woman, lovey, I've noticed that. You were malleable enough at the beginning. That was the way you were bred to be, of course."

"I wasn't bred to be anything."

"How do you know?" he said. "Two minutes ago you were claiming you don't even remember the past. How do you know what you were meant to be? Made to be?" He glanced down the well. "The memory's in your head somewhere, lovey. You just have to be willing to coax it out. If Quaisoir sought some Goddess, maybe you did too, even if you don't remember it. And if you did, then maybe you're more than Joshua's Peachplum. Maybe you've got some place in the action I haven't accounted for."

"Where would I meet Goddesses, Dowd?" Jude replied. "I've lived in the Fifth, in London, in Notting Hill Gate. There are no Goddesses."

Even as she spoke she thought of Celestine, buried beneath the Tabula Rasa's tower. Was she a sister to the deities that haunted Yzordderrex? A transforming force, locked away by a sex that worshiped fixedness? At the memory of the prisoner, and her cell, Jude's mind grew suddenly light, as though she'd downed a whisky on an empty stomach. She had been touched by the miraculous, after all. So if once, why not many times? If now, why not in her forgotten past?

"I've got no way back," she said, protesting the difficulty of this as much for her own benefit as Dowd's.

"It's easy," he replied. "Just think of what it was like to be born."

"I don't even remember my childhood."

"You had no childhood, lovey. You had no adolescence. You were born just the way you are, overnight. Quaisoir was the first Judith, and you, my sweet, are only her replica. Perfect, maybe, but stilt a replica."

"I won't... I don't... believe you."

"Of course you must refuse the truth at first. It's perfectly understandable. But your body knows what's true and what isn't. You're shaking, inside and out...."

"I'm tired," she said, knowing the explanation was pitifully weak.

"You're feeling more than weary," Dowd said. "Admit it."

As he pried, she remembered the results of his last revelations about her past: how she'd dropped to the kitchen floor, hamstrung by invisible knives. She dared not succumb to such a collapse now, with the well a foot from where she stood, and Dowd knew it.

"You have to face the memories," he was saying. "Just spit them out. Go on. You'll feel better for it, I promise you."

She could feel both her limbs and her resolve weakening as he spoke, but the prospect of facing whatever lay in the darkness at the back of her skull—and however much she distrusted Dowd, she didn't doubt there was something horrendous there—was almost as terrifying as the thought of the well taking her. Perhaps it would be better to die here and now, two sisters extinguished within the same hour, and never know whether Dowd's claims were true or not. But then suppose he'd been lying to her all along—the actor chappie's finest performance yet—and she was not a shadow, not a replica, not a thing bred to do service, but a natural child with natural parents: a creature unto herself, real, complete? Then she'd be giving herself to death out of fear of self-discovery, and Dowd would have claimed another victim. The only way to defeat him was to call his bluff; to do as he kept urging her to do and go into the darkness at the back of her head, ready to embrace whate

ver revelations it concealed. Whichever Judith she was, she was; whether real or replica, natural or bred. There was no escape from herself in the living world. Better to know the truth, once and for all.

The decision ignited a flame in her skull, and the first phantoms of the past appeared in her mind's eye.

"Oh, my Goddess," she murmured, throwing back her head. "What is this? What is this?"

She saw herself lying on bare boards in an empty room, a fire burning in the grate, warming her in her sleep and flattering her nakedness with its tuster. Somebody had marked her body while she slept, daubing upon it a design she recognized—the glyph she'd first seen in her mind's eye when she'd made love with Oscar, then glimpsed again as she passed between Dominions—the spiraling sign of her flesh, here painted on flesh itself in half a dozen colors.

She moved in her sleep, and the whorls seemed to leave traces of themselves in the air where she'd been, their persistence exciting another motion, this other in the ring of sand that bounded her hard bed. It rose around her like the curtain of the Borealis, shimmering with the same colors in which her glyph had been painted, as though something of her essential anatomy was in the very air of the room. She was entranced by the beauty of the sight.

"What are you seeing?" she heard Dowd asking her.

"Me," she said, "lying on the floor ... in a circle of sand...."

"Are you sure it's you?" he said.

She was about to pour scorn on his question, when she realized its import. Perhaps this wasn't her, but her sister.

"Is there any way of knowing?" she said.

"You'll soon see," he told her.

So she did. The curtain of sand began to wave more violently, as if seized by a wind unleashed within the circle. Particles flew from it, intensifying as they were thrown against the dark air: motes of the purest color rising like new stars, then dropping again, burning in their descent, towards the place where she, the witness, lay. She was lying on the ground close to her sister, receiving the rain of color like a grateful earth, needing its sustenance if she was to grow and swell and become fruitful.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

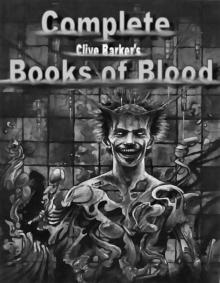

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

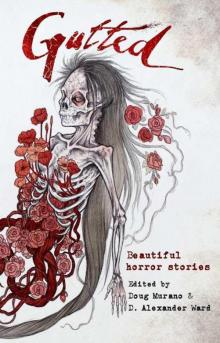

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

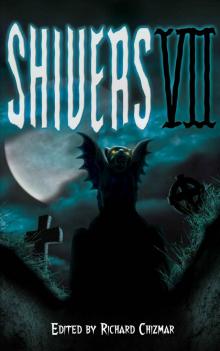

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

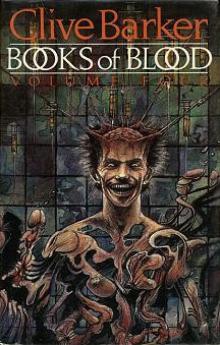

Books Of Blood Vol 4