- Home

- Clive Barker

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Page 2

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Read online

Page 2

Harry was impressed. It had taken him twenty years to learn how arbitrary things were. She spoke it as conventional wisdom.

'Where is your husband?' he asked her.

'Upstairs,' she said. 'I had the body brought back here, where I could look after him. I can't pretend I understand what's going on, but I'm not going to risk ignoring his instructions.'

Harry nodded.

'Swann was my life,' she added softly, apropos of nothing; and everything.

She took him upstairs. The perfume that had met him at the door intensified. The master bedroom had been turned into a Chapel of Rest, knee-deep in sprays and wreaths of every shape and variety; their mingled scents verged on the hallucinogenic. In the midst of this abundance, the casket - an elaborate affair in black and silver - was mounted on trestles. The upper half of the lid stood open, the plush overlay folded back. At Dorothea's invitation he waded through the tributes to view the deceased. He liked Swann's face; it had humour, and a certain guile; it was even handsome in its weary way. More: it had inspired the love of Dorothea; a face could have few better recommendations. Harry stood waist-high in flowers and, absurd as it was, felt a twinge of envy for the love this man must have enjoyed.

'Will you help me, Mr D'Amour?'

What could he say but: 'Yes, of course I'll help.' That, and: 'Call me Harry.'

He would be missed at Wing's Pavilion tonight. He had occupied the best table there every Friday night for the past six and a half years, eating at one sitting enough to compensate for what his diet lacked in excellence and variety the other six days of the week. This feast - the best Chinese cuisine to be had south of Canal Street - came gratis, thanks to services he had once rendered the owner. Tonight the table would go empty.

Not that his stomach suffered. He had only been sitting with Swann an hour or so when Valentin came up and said:

'How do you like your steak?'

'Just shy of burned,' Harry replied.

Valentin was none too pleased by the response. 'I hate to overcook good steak/ he said.

'And I hate the sight of blood,' Harry said, 'even if it isn't my own.'

The chef clearly despaired of his guest's palate, and turned to go.

'Valentin?'

The man looked round.

'Is that your Christian name?' Harry asked.

'Christian names are for Christians,' came the reply.

Harry nodded. 'You don't like my being here, am I right?'

Valentin made no reply. His eyes had drifted past Harry to the open coffin.

'I'm not going to be here for long,' Harry said, 'but while I am, can't we be friends?'

Valentin's gaze found him once more.

'I don't have any friends,' he said without enmity or self-pity. 'Not now.'

'OK. I'm sorry.'

'What's to be sorry for?' Valentin wanted to know. 'Swann's dead. It's all over, bar the shouting.'

The doleful face stoically refused tears. A stone would weep sooner, Harry guessed. But there was grief there, and all the more acute for being dumb.

'One question.'

'Only one?'

'Why didn't you want me to read his letter?'

Valentin raised his eyebrows slightly; they were fine enough to have been pencilled on. 'He wasn't insane,' he said. 'I didn't want you thinking he was a crazy man, because of what he wrote. What you read you keep to yourself. Swann was a legend. I don't want his memory besmirched.'

'You should write a book,' Harry said. 'Tell the whole story once and for all. You were with him a long time, I hear.'

'Oh yes,' said Valentin. 'Long enough to know better than to tell the truth.'

So saying he made an exit, leaving the flowers to wilt, and Harry with more puzzles on his hands than he'd begun with.

Twenty minutes later, Valentin brought up a tray of food: a large salad, bread, wine, and the steak. It was one degree short of charcoal.

'Just the way I like it,' Harry said, and set to guzzling.

He didn't see Dorothea Swann, though God knows he thought about her often enough. Every time he heard a whisper on the stairs, or footsteps along the carpetted landing, he hoped her face would appear at the door, an invitation on her lips. Not perhaps the most appropriate of thoughts, given the proximity of her husband's corpse, but what would the illusionist care now? He was dead and gone. If he had any generosity of spirit he wouldn't want to see his widow drown in her grief.

Harry drank the half-carafe of wine Valentin had brought, and when - three-quarters of an hour later - the man re-appeared with coffee and Calvados, he told him to leave the bottle.

Nightfall was near. The traffic was noisy on Lexington and Third. Out of boredom he took to watching the street from the window. Two lovers feuded loudly on the sidewalk, and only stopped when a brunette with a hare-lip and a pekinese stood watching them shamelessly. There were preparations for a party in the brownstone opposite: he watched a table lovingly laid, and candles lit. After a time the spying began to depress him, so he called Valentin and asked if there was a portable television he could have access to. No sooner said than provided, and for the next two hours he sat with the small black and white monitor on the floor amongst the orchids and the lilies, watching whatever mindless entertainment it offered, the silver luminescence flickering on the blooms like excitable moonlight.

A quarter after midnight, with the party across the street in full swing, Valentin came up. 'You want a night-cap?' he asked.

'Sure.'

'Milk; or something stronger?'

'Something stronger.'

He produced a bottle of fine cognac, and two glasses. Together they toasted the dead man.

'Mr Swann.'

'Mr Swann.'

'If you need anything more tonight,' Valentin said, 'I'm in the room directly above. Mrs Swann is down- stairs, so if you hear somebody moving about, don't worry. She doesn't sleep well these nights.'

'Who does?' Harry replied.

Valentin left him to his vigil. Harry heard the man's tread on the stairs, and then the creaking of floorboards on the level above. He returned his attention to the television, but he'd lost the thread of the movie he'd been watching. It was a long stretch 'til dawn; meanwhile New York would be having itself a fine Friday night: dancing, fighting, fooling around.

The picture on the television set began to flicker. He stood up, and started to walk across to the set, but he never got there. Two steps from the chair where he'd been sitting the picture folded up and went out altogether, plunging the room into total darkness. Harry briefly had time to register that no light was finding its way through the windows from the street. Then the insanity began.

Something moved in the blackness: vague forms rose and fell. It took him a moment to recognise them. The flowers! Invisible hands were tearing the wreaths and tributes apart, and tossing the blossoms up into the air. He followed their descent, but they didn't hit the ground. It seemed the floorboards had lost all faith in themselves, and disappeared, so the blossoms just kept falling - down, down - through the floor of the room below, and through the basement floor, away to God alone knew what destination. Fear gripped Harry, like some old dope-pusher promising a terrible high. Even those few boards that remained beneath his feet were becoming insubstantial. In seconds he would go the way of the blossoms.

He reeled around to locate the chair he'd got up from - some fixed point in this vertiginous nightmare. The chair was still there; he could just discern its form in the gloom. With torn blossoms raining down upon him he reached for it, but even as his hand took hold of the arm, the floor beneath the chair gave up the ghost, and now, by a ghastly light that was thrown up from the pit that yawned beneath his feet, Harry saw it tumble away into Hell, turning over and over 'til it was pin-prick small.

Then it was gone; and the flowers were gone, and the walls and the windows and every damn thing was gone but him.

Not quite everything. Swann's casket remained, its lid still standing open, it

s overlay neatly turned back like the sheet on a child's bed. The trestle had gone, as had the floor beneath the trestle. But the casket floated in the dark air for all the world like some morbid illusion, while from the depths a rumbling sound accompanied the trick like the roll of a snare- drum.

Harry felt the last solidity failing beneath him; felt the pit call. Even as his feet left the ground, that ground faded to nothing, and for a terrifying moment he hung over the Gulfs, his hands seeking the lip of the casket. His right hand caught hold of one of the handles, and closed thankfully around it. His arm was almost jerked from its socket as it took his body-weight, but he flung his other arm up and found the casket-edge. Using it as purchase, he hauled himself up like a half-drowned sailor. It was a strange lifeboat, but then this was a strange sea. Infinitely deep, infinitely terrible.

Even as he laboured to secure himself a better hand- hold, the casket shook, and Harry looked up to discover that the dead man was sitting upright. Swann's eyes opened wide. He turned them on Harry; they were far from benign. The next moment the dead illusionist was scrambling to his feet - the floating casket rocking ever more violently with each movement. Once vertical, Swann proceeded to dislodge his guest by grinding his heel in Harry's knuckles. Harry looked up at Swann, begging for him to stop.

The Great Pretender was a sight to see. His eyes were starting from his sockets; his shirt was torn open to display the exit-wound in his chest. It was bleeding afresh. A rain of cold blood fell upon Harry's upturned face. And still the heel ground at his hands. Harry felt his grip slipping. Swann, sensing his approaching triumph, began to smile.

'Fall, boy!' he said. 'Fall!'

Harry could take no more. In a frenzied effort to save himself he let go of the handle in his right hand, and reached up to snatch at Swann's trouser-leg. His fingers found the hem, and he pulled. The smile vanished from the illusionist's face as he felt his balance go. He reached behind him to take hold of the casket lid for support, but the gesture only tipped the casket further over. The plush cushion tumbled past Harry's head; blossoms followed.

Swann howled in his fury and delivered a vicious kick to Harry's hand. It was an error. The casket tipped over entirely and pitched the man out. Harry had time to glimpse Swann's appalled face as the illusionist fell past him. Then he too lost his grip and tumbled after him.

The dark air whined past his ears. Beneath him, the Gulfs spread their empty arms. And then, behind the rushing in his head, another sound: a human voice.

'Is he dead?' it inquired.

'No,' another voice replied, 'no, I don't think so. What's his name, Dorothea?'

'D'Amour.'

'Mr D'Amour? Mr D'Amour?'

Harry's descent slowed somewhat. Beneath him, the Gulfs roared their rage.

The voice came again, cultivated but unmelodious. 'Mr D'Amour.'

'Harry,' said Dorothea.

At that word, from that voice, he stopped falling; felt himself borne up. He opened his eyes. He was lying on a solid floor, his head inches from the blank television screen. The flowers were all in place around the room, Swann in his casket, and God - if the rumours were to be believed - in his Heaven.

'I'm alive,' he said.

He had quite an audience for his resurrection. Dorothea of course, and two strangers. One, the owner of the voice he'd first heard, stood close to the door. His features were unremarkable, except for his brows and lashes, which were pale to the point of invisibility. His female companion stood nearby. She shared with him this distressing banality, stripped bare of any feature that offered a clue to their natures.

'Help him up, angel,' the man said, and the woman bent to comply. She was stronger than she looked, readily hauling Harry to his feet. He had vomited in his strange sleep. He felt dirty and ridiculous.

'What the hell happened?' he asked, as the woman escorted him to the chair. He sat down.

'He tried to poison you,' the man said.

'Who did?'

'Valentin, of course.'

'Valentin?'

'He's gone,' Dorothea said. 'Just disappeared.' She was shaking. 'I heard you call out, and came in here to find you on the floor. I thought you were going to choke.'

'It's all right,' said the man, 'everything is in order now.'

'Yes,' said Dorothea, clearly reassured by his bland smile. 'This is the lawyer I was telling you about, Harry. Mr Butterfield.'

Harry wiped his mouth. 'Please to meet you,' he said.

'Why don't we all go downstairs?' Butterfield said. 'And I can pay Mr D'Amour what he's due.'

'It's all right,' Harry said, 'I never take my fee until the job's done.'

'But it is done,' Butterfield said. 'Your services are no longer required here.'

Harry threw a glance at Dorothea. She was plucking a withered anthurium from an otherwise healthy spray.

'I was contracted to stay with the body -'

'The arrangements for the disposal of Swann's body have been made,' Butterfield returned. His courtesy was only just intact. 'Isn't that right, Dorothea?'

'It's the middle of the night,' Harry protested. 'You won't get a cremation until tomorrow morning at the earliest.'

Thank you for your help,' Dorothea said. 'But I'm sure everything will be fine now that Mr Butterfield has arrived. Just fine.'

Butterfield turned to his companion.

'Why don't you go out and find a cab for Mr D'Amour?' he said. Then, looking at Harry: 'We don't want you walking the streets, do we?'

All the way downstairs, and in the hallway as Butterfield paid him off, Harry was willing Dorothea to contradict the lawyer and tell him she wanted Harry to stay. But she didn't even offer him a word of farewell as he was ushered out of the house. The two hundred dollars he'd been given were, of course, more than adequate recompense for the few hours of idleness he'd spent there, but he would happily have burned all the bills for one sign that Dorothea gave a damn that they were parting. Quite clearly she did not. On past experience it would take his bruised ego a full twenty-four hours to recover from such indifference.

He got out of the cab on 3rd around 83rd Street, and walked through to a bar on Lexington where he knew he could put half a bottle of bourbon between himself and the dreams he'd had.

It was well after one. The street was deserted, except for him, and for the echo his footsteps had recently acquired. He turned the corner into Lexington, and waited. A few beats later, Valentin rounded the same corner. Harry took hold of him by his tie.

'Not a bad noose,' he said, hauling the man off his heels.

Valentin made no attempt to free himself. 'Thank God you're alive,' he said.

'No thanks to you,' Harry said. 'What did you put in the drink?'

'Nothing,' Valentin insisted. 'Why should I?'

'So how come I found myself on the floor? How come the bad dreams?'

'Butterfield,' Valentin said. 'Whatever you dreamt, he brought with him, believe me. I panicked as soon as I heard him in the house, I admit it. I know I should have warned you, but I knew if I didn't get out quickly I wouldn't get out at all.'

'Are you telling me he would have killed you?'

'Not personally; but yes.' Harry looked incredulous. 'We go way back, him and me.'

'He's welcome to you,' Harry said, letting go of the tie. 'I'm too damn tired to take any more of this shit.' He turned from Valentin and began to walk away.

'Wait -' said the other man, '- I know I wasn't too sweet with you back at the house, but you've got to understand, things are going to get bad. For both of us.'

'I thought you said it was all over bar the shouting?'

'I thought it was. I thought we had it all sewn up. Then Butterfield arrived and I realised how naive I was being. They're not going to let Swann rest in peace. Not now, not ever. We have to save him, D'Amour.'

Harry stopped walking and studied the man's face. To pass him in the street, he mused, you wouldn't have taken him for a lunatic.

'Did Butterfield g

o upstairs?' Valentin enquired.

'Yes he did. Why?'

'Do you remember if he approached the casket?'

Harry shook his head.

'Good,' said Valentin. 'Then the defences are holding, which gives us a little time. Swann was a fine tactician, you know. But he could be careless. That was how they caught him. Sheer carelessness. He knew they were coming for him. I told him outright, I said we should cancel the remaining performances and go home. At least he had some sanctuary there.'

'You think he was murdered?'

'Jesus Christ,' said Valentin, almost despairing of Harry, 'of course he was murdered.'

'So he's past saving, right? The man's dead.'

'Dead; yes. Past saving? no.'

'Do you talk gibberish to everyone?'

Valentin put his hand on Harry's shoulder, 'Oh no,' he said, with unfeigned sincerity. 'I don't trust anyone the way I trust you.'

'This is very sudden,' said Harry. 'May I ask why?'

'Because you're in this up to your neck, the way I am,' Valentin replied.

'No I'm not,' said Harry, ,but Valentin ignored the denial, and went on with his talk. 'At the moment we don't know how many of them there are, of course. They might simply have sent Butterfield, but I think that's unlikely.'

'Who's Butterfield with? The Mafia?'

'We should be so lucky,' said Valentin. He reached in his pocket and pulled out a piece of paper. 'This is the woman Swann was with,' he said, 'the night at the theatre. It's possible she knows something of their strength.'

There was a witness?'

'She didn't come forward, but yes, there was. I was his procurer you see. I helped arrange his several adulteries, so that none ever embarrassed him. See if you can get to her -' He stopped abruptly. Somewhere close by, music was being played. It sounded like a drunken jazz band extemporising on bagpipes; a wheezing, rambling cacophony. Valentin's face instantly became a portrait of distress. 'God help us ...' he said softly, and began to back away from Harry.

'What's the problem?'

'Do you know how to pray?' Valentin asked him as he retreated down 83rd Street. The volume of the music was rising with every interval.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

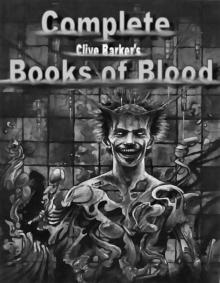

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

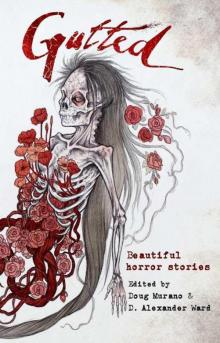

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

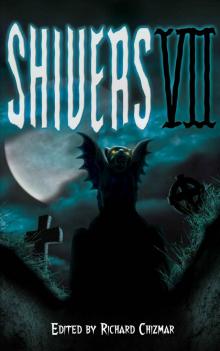

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

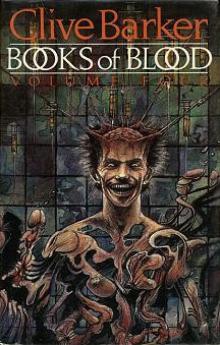

Books Of Blood Vol 4