- Home

- Clive Barker

Books of Blood Vol 2 Page 11

Books of Blood Vol 2 Read online

Page 11

Later, before his suicide, the other gunman had told him Jacqueline had gone to Amsterdam. This he knew for a fact, from a man called Koos. And so the circle begins to close, yes?

I was in Amsterdam seven weeks, without finding a single clue to her whereabouts, until yesterday evening. Seven weeks of celibacy, which is unusual for me. Listless with frustration I went down to the red-light district, to find a woman. They sit there you know, in the windows, like mannequins, beside pink-fringed lamps. Some have miniature dogs on their laps; some read. Most just stare out at the street, as if mesmerized.

There were no faces there that interested me. They all seemed joyless, lightless, too much unlike her. Yet I couldn't leave. I was like a fat boy in a sweet shop, too nauseous to buy, too gluttonous to go.

Towards the middle of the night, I was spoken to out of the crowd by a young man who, on closer inspection, was not young at all, but heavily made up. He had no eyebrows, just pencil marks drawn on to his shiny skin. A cluster of gold earrings in his left ear, a half-eaten peach in his white-gloved hand, open sandals, lacquered toenails. He took hold of my sleeve, proprietarily.

I must have sneered at his sickening appearance, but he didn't seem at all upset by my contempt. You look like a man of discernment, he said. I looked nothing of the kind: you must be mistaken, I said. No, he replied, I am not mistaken. You are Oliver Vassi.

My first thought, absurdly, was that he intended to kill me. I tried to pull away; his grip on my cuff was relentless.

You want a woman, he said. Did I hesitate enough for him to know I meant yes, though I said no? I have a woman like no other, he went on, She's a miracle. I know you'll want to meet her in the flesh.

What made me know it was Jacqueline he was talking about? Perhaps the fact that he had known me from out of the crowd, as though she was up at a window somewhere, ordering her admirers to be brought to her like a diner ordering lobster from a tank. Perhaps too the way his eyes shone at me, meeting mine without fear because fear, like rapture, he felt only in the presence of one creature on God's cruel earth. Could I not also see myself reflected in his perilous look? He knew Jacqueline, I had no doubt of it.

He knew I was hooked, because once I hesitated he turned away from me with a mincing shrug, as if to say: you missed your chance. Where is she? I said, seizing his twig-thin arm. He cocked his head down the street and I followed him, suddenly as witless as an idiot, out of the throng. The road emptied as we walked; the red lights gave way to gloom, and then to darkness. If I asked him where we were going once I asked him a dozen times; he chose not to answer, until we reached a narrow door in a narrow house down some razor-thin street. We're here, he announced, as though the hovel were the Palace of Versailles.

Up two flights in the otherwise empty house there was a room with a black door. He pressed me to it. It was locked.

"See," he invited, "She's inside."

"It's locked," I replied. My heart was fit to burst: she was near, for certain, I knew she was near.

"See," he said again, and pointed to a tiny hole in the panel of the door. I devoured the light through it, pushing my eye towards her through the tiny hole.

The squalid interior was empty, except for a mattress and Jacqueline. She lay spread-eagled, her wrists and ankles bound to rough posts set in the bare floor at the four corners of the mattress.

"Who did this?" I demanded, not taking my eye from her nakedness.

"She asks," he replied. "It is her desire. She asks." She had heard my voice; she cranked up her head with some difficulty and stared directly at the door. When she looked at me all the hairs rose on my head, I swear it, in welcome, and swayed at her command.

"Oliver," she said.

"Jacqueline." I pressed the word to the wood with a kiss.

Her body was seething, her shaved sex opening and closing like some exquisite plant, purple and lilac and rose.

"Let me in," I said to Koos.

"You will not survive one night with her."

"Let me in."

"She is expensive," he warned.

"How much do you want?"

"Everything you have. The shirt off your back, your money, your jewellery; then she is yours."

I wanted to beat the door down, or break his nicotine stained fingers one by one until he gave me the key. He knew what I was thinking.

"The key is hidden," he said, "And the door is strong. You must pay, Mr Vassi. You want to pay."

It was true. I wanted to pay.

"You want to give me all you have ever owned, all you have ever been. You want to go to her with nothing to claim you back. I know this. It's how they all go to her."

"All? Are there many?"

"She is insatiable," he said, without relish. It wasn't a pimp's boast: it was his pain, I saw that clearly. "I am always finding more for her, and burying them."

Burying them.

That, I suppose, is Koos' function; he disposes of the dead. And he will get his lacquered hands on me after tonight; he will fetch me off her when I am dry and useless to her, and find some pit, some canal, some furnace to lose me in. The thought isn't particularly attractive.

Yet here I am with all the money I could raise from selling my few remaining possessions on the table in front of me, my dignity gone, my life hanging on a thread, waiting for a pimp and a key.

It's well dark now, and he's late. But I think he is obliged to come. Not for the money, he probably has few requirements beyond his heroin and his mascara. He will come to do business with me because she demands it and he is in thrall to her, every bit as much as I am. Oh, he will come. Of course he will come.

Well, I think that is sufficient.

This is my testimony. I have no time to re-read it now. His footsteps are on the stairs (he limps) and I must go with him. This I leave to whoever finds it, to use as they think fit. By morning I shall be dead, and happy. Believe it."

My God, she thought, Koos has cheated me.

Vassi had been outside the door, she'd felt his flesh with her mind and she'd embraced it. But Koos hadn't let him in, despite her explicit orders. Of all men, Vassi was to be allowed free access, Koos knew that. But he'd cheated her, the way they'd all cheated her except Vassi. With him (perhaps) it had been love.

She lay on the bed through the night, never sleeping. She seldom slept now for more than a few minutes: and only then with Koos watching her. She'd done herself harm in her sleep, mutilating herself without knowing it, waking up bleeding and screaming with every limb sprouting needles she'd made out of her own skin and muscle, like a flesh cactus.

It was dark again, she guessed, but it was difficult to be sure. In this heavily curtained, bare-bulb lit room, it was a perpetual day to the senses, perpetual night to the soul. She would lie, bed-sores on her back, on her buttocks, listening to the far sounds of the street, sometimes dozing for a while, sometimes eating from Koos' hand, being washed, being toileted, being used.

A key turned in the lock. She strained from the mattress to see who it was. The door was opening... opening... opened.

Vassi. Oh God, it was Vassi at last, she could see him crossing the room towards her.

Let this not be another memory, she prayed, please let it be him this time: true and real.

"Jacqueline."

He said the name of her flesh, the whole name.

"Jacqueline." It was him.

Behind him, Koos stared between her legs, fascinated by the dance of her labia.

"Koo..." she said, trying to smile.

"I brought him," he grinned at her, not looking away from her sex.

"A day," she whispered. "I waited a day, Koos. You made me wait —"

"What's a day to you?" he said, still grinning.

She didn't need the pimp any longer, not that he knew that. In his innocence he thought Vassi was just another man she'd seduced along the way; to be drained and discarded like the others. Koos believed he would be needed tomorrow; that's why he played this fatal game

so artlessly.

"Lock the door," she suggested to him. "Stay if you like."

"Stay?" he said, leering. "You mean, and watch?"

He watched anyway. She knew he watched through that hole he had bored in the door; she could hear him pant sometimes. But this time, let him stay forever.

Carefully, he took the key from the outside of the door, closed it, slipped the key into the inside and locked it. Even as the lock clicked she killed him, before he could even turn round and look at her again. Nothing spectacular in the execution; she just reached into his pigeon chest and crushed his lungs. He slumped against the door and slid down, smearing his face across the wood.

Vassi didn't even turn round to see him die; she was all he ever wanted to look at again.

He approached the mattress, crouched, and began to untie her ankles. The skin was chafed, the rope scabby with old blood. He worked at the knots systematically, finding a calm he thought he'd lost, a simple contentment in being here at the end, unable to go back, and knowing that the path ahead was deep in her.

When her ankles were free, he began on her wrists, interrupting her view of the ceiling as he bent over her. His voice was soft.

"Why did you let him do this to you?"

"I was afraid."

"Of what?"

"To move; even to live. Every day, agony."

"Yes."

He understood so well that total incapacity to exist.

She felt him at her side, undressing, then laying a kiss on the sallow skin of the stomach of the body she occupied. It was marked with her workings; the skin had been stretched beyond its tolerance and was permanently criss-crossed.

He lay down beside her, and the feel of his body against hers was not unpleasant.

She touched his head. Her joints were stiff, the movements painful, but she wanted to draw his face up to hers. He came, smiling, into her sight, and they exchanged kisses.

My God, she thought, we are together.

And thinking they were together, her will was made flesh. Under his lips her features dissolved, becoming the red sea he'd dreamt of, and washing up over his face, that was itself dissolving; common waters made of thought and bone.

Her keen breasts pricked him like arrows; his erection, sharpened by her thought, killed her in return with his only thrust. Tangled in a wash of love they thought themselves extinguished, and were.

Outside, the hard world mourned on, the chatter of buyers and sellers continuing through the night. Eventually indifference and fatigue claimed even the eagerest merchant. Inside and out there was a healing silence: an end to losses and to gains.

THE SKINS OF THE FATHERS

THE CAR COUGHED, and choked, and died. Davidson was suddenly aware of the wind on the desert road, as it keened at the windows of his Mustang. He tried to revive the engine, but it refused life. Exasperated, Davidson let his sweating hands drop off the wheel and surveyed the territory. In every direction, hot air, hot rock, hot sand. This was Arizona.

He opened the door and stepped out on to the baking dust highway. In front and behind it stretched unswervingly to the pale horizon. If he narrowed his eyes he could just make out the mountains, but as soon as he attempted to fix his focus they were eaten up by the heat-haze. Already the sun was corroding the top of his head, where his blond hair was thinning. He threw up the hood of the car and peered hopelessly into the engine, regretting his lack of mechanical know-how. Jesus, he thought, why don't they make the damn things foolproof? Then he heard the music.

It was so far off it sounded like a whistling in his ears at first: but it became louder.

It was music, of a sort.

How did it sound? Like the wind through telephone lines, a sourceless, rhythmless, heartless air-wave plucking at the hairs on the back of his neck and telling them to stand. He tried to ignore it, but it wouldn't go away.

He looked up out of the shade of the bonnet to find the players, but the road was empty in both directions. Only as he scanned the desert to the southeast did a line of tiny figures become visible to him, walking, or skipping, or dancing at the furthest edge of his sight, liquid in the heat of the earth. The procession, if that was its nature, was long, and making its way across the desert parallel to the highway. Their paths would not cross.

Davidson glanced down once more into the cooling entrails of his vehicle and then up again at the distant line of dancers.

He needed help: no doubt of it.

He started off across the desert towards them.

Once off the highway the dust, not impacted by the passage of cars, was loose: it flung itself up at his face with every step. Progress was slow: he broke into a trot: but they were receding from him. He began to run.

Over the thunder of his blood, he could hear the music more loudly now. There was no melody apparent, but a constant rising and falling of many instruments; howls and hummings, whistlings, drummings and roarings.

The head of the procession had now disappeared, received into distance, but the celebrants (if that they were) still paraded past. He changed direction a little, to head them off, glancing over his shoulder briefly to check his way back. With a stomach-churning sense of loneliness he saw his vehicle, as small as a beetle on the road behind him, sitting weighed down by a boiling sky.

He ran on. A quarter of an hour, perhaps, and he began to see the procession more clearly, though its leaders were well out of sight. It was, he began to believe, a carnival of some sort, extraordinary as that seemed out here in the middle of God's nowhere. The last dancers in the parade were definitely costumed, however. They wore headdresses and masks that tottered well above human height — there was the flutter of brightly-coloured feathers, and streamers coiling in the air behind them. Whatever the reason for the celebration they reeled like drunkards, loping one moment, leaping the next, squirming, some of them, on the ground, bellies to the hot sand.

Davidson's lungs were torn with exhaustion, and it was clear he was losing the pursuit. Having gained on the procession, it was now moving off faster than he had strength or willpower to follow.

He stopped, bracing his arms on his knees to support his aching torso, and looked under his sweat-sodden brow at his disappearing salvation. Then, summoning up all the energy he could muster, he yelled: Stop!

At first there was no response. Then, through the slits of his eyes, he thought he saw one or two of the revelers halt. He straightened up. Yes, one or two were looking at him. He felt, rather than saw, their eyes upon him.

He began to walk towards them.

Some of the instruments had died away, as though word of his presence was spreading among them. They'd definitely seen him, no doubt of that.

He walked on, faster now, and out of the haze, the details of the procession began to come clear.

His pace slowed a little. His heart, already pounding with exertion, thudded in his chest.

— My Jesus, he said, and for the first time in his thirty-six godless years the words were a true prayer.

He stood off half a mile from them, but there was no mistaking what he saw. His aching eyes knew papier-mâché from flesh, illusion from misshapen reality.

The creatures at the end of the procession, the least of the least, the hangers-on, were monsters whose appearance beggared the nightmares of insanity.

One was perhaps eighteen or twenty feet tall. Its skin, that hung in folds on its muscle, was a sheath of spikes, its head a cone of exposed teeth, set in scarlet gums. Another was three-winged, its triple ended tail thrashing the dust with reptilian enthusiasm. A third and fourth were married together in a union of monstrosities the result of which was more disgusting than the sum of its parts. Through its length and breadth this symbiotic horror was locked in seeping marriage, its limbs thrust in and through wounds in its partner's flesh. Though the tongues of its heads were wound together it managed a cacophonous howl.

Davidson took a step back, and glanced round at the car and the highway. As he did so one of the t

hings, black and red, began to scream like a whistle. Even at a half mile's distance the noise cut into Davidson's head. He looked back at the procession.

The whistling monster had left its place in the parade, and its clawed feet were pounding the desert as it began to race towards him. Uncontrollable panic swept through Davidson, and he felt his trousers fill as his bowels failed him.

The thing was rushing towards him with the speed of a cheetah, growing with every second, so he could see more detail of its alien anatomy with every step. The thumbless hands with their toothed palms, the head that bore only a tri-coloured eye, the sinew of its shoulder and chest, even its genitals, erect with anger, or (God help me) lust, two-pronged and beating against its abdomen.

Davidson shrieked a shriek that was almost the equal of the monster's noise, and fled back the way he had come.

The car was a mile, two miles away, and he knew it offered no protection were he to reach it before the monster overcame him. In that moment he realized how close death was, how close it had always been, and he longed for a moment's comprehension of this idiot honor.

It was already close behind him as his shit-slimed legs buckled, and he fell, and crawled, and dragged himself towards the car. As he heard the thud of its feet at his back he instinctively huddled into a ball of whimpering flesh, and awaited the coup de grace.

He waited two heart-beats.

Three. Four. Still it didn't come.

The whistling voice had grown to an unbearable pitch, and was now fading a little. The gnashing palms did not connect with his body. Cautiously, expecting his head to be snapped from his neck at any moment, he peered through his fingers.

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

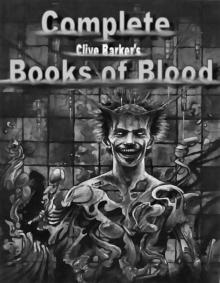

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

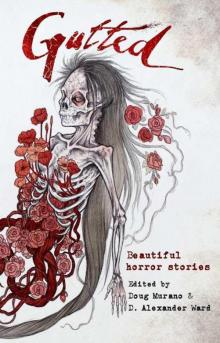

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

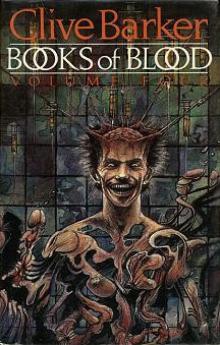

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4