- Home

- Clive Barker

Abarat: Absolute Midnight Page 15

Abarat: Absolute Midnight Read online

Page 15

“I know that’s the way it was before, Candy, but like I said, things have changed.”

“No that much.”

As she spoke she felt a strange tingling sensation at the top of her spine, and slowly, slowly—almost as if in a nightmare—she turned back to see something her soul told her not to look at. Too late.

There was her father, coming out of the house. And he was staring right at her.

Chapter 25

No More Lies

CANDY HAD FACED MORE than her share of monstrous enemies in the last few months: Kaspar Wolfswinkel in his prison house on Ninnyhammer; the Zethek, crazed in the holds of the humble fishing boat Parroto Parroto; and the many Beasts of Efreet, one of whom had slaughtered Diamanda.

And not forgetting, of course, the creature who’d waited for Candy in the house where she’d taken refuge after Diamanda’s death: Christopher Carrion.

And the Hag, Mater Motley.

And Princess Boa.

But none of these monsters prepared her for this confrontation, with her very own father. Here he was, and he could see her.

Things had changed, just as her mother had warned.

“You thought you’d slip in here and spy on good Christian people without being seen? Think again. I see witches very clearly.” He held up the Bible he was carrying in his hand. “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live!”

This sounded so utterly preposterous coming from her father’s mouth that she couldn’t help but laugh. His face, which had always gone red when he flew into a temper, instead became pale, draining of blood.

“You mock me, you mock the Great One,” he said. His tone was calm, remote. “Do so if you wish. Laugh yourself into the flames of perdition.”

Candy stopped laughing. Not out of fear, but out of puzzlement. Her father had changed. The puffiness had gone from his face, and there was a new intensity in his eyes, replacing the blur of beer. He was leaner too. The extra pounds that had softened his jawline had gone. Nor was he combing his last few hairs over his head from side to side in a pitiful attempt to conceal his loss of hair. He had shaved it off. He was now completely bald.

“I don’t know what your mother’s been telling you, but I’m sure it’s lies,” he said.

“She just said you and Ricky go to church together.”

“Oh, indeed we do. Those of us with brains in our heads have seen the light. Ricky! Come out here! We’ve got a visitor.”

Candy threw a glance up at her mom. There were so many contrary emotions fighting for Melissa’s face that Candy couldn’t figure out what she was really feeling.

“Your mother can’t help you,” Bill said to Candy. “So I’d put her out of your head, if I were you. There’s only one man of vision left in Chickentown these days, and you’re looking at him. Ricky! When I tell you to get out here, you do it!”

While her father was looking toward the house, Candy glanced down at the vest he was wearing. Even by Abaratian standards it would have been thought outlandish. It was made from a patchwork of various thick fabrics—one striped, one polka-dotted, one black—but possessing an odd iridescence. She knew she’d seen this odd combination of colors before. But where? She was still puzzling over the mystery when Ricky appeared from the house. Her brother’s hair had been shaved off as well and he looked skinnier than ever. His eyes looked huge, like an anxious baby.

He’s so afraid, Candy thought. Poor Ricky. Afraid of the man who’s supposed to be his protector. No, not afraid: terrified.

“I was getting a clean T-shirt, Dad—I mean, Reverend, sir.”

“I don’t care what you were doing,” Bill snapped. “When I call you, you’ve got how long?”

“Ten seconds, Dad. No. I mean—sorry, sir. Reverend. I mean, Reverend.”

“Finally, the boy says something I can bear listening to. Now, I want you to take a deep breath, boy. And I want you to rest that stupid, stupid, stupid brain of yours. Do you understand what you need to do?”

“I guess so.”

“It’s real simple, son. Just don’t think.”

“About anything?”

“About anything. I just want you to close your eyes. That’s good. You’re perfectly safe.”

Candy threw a puzzled glance toward her mother, but Melissa was watching her husband. There was not so much as a flicker of affection on her face. If she had ever really loved him, it seemed, that love had been poured away, every last drop of it. In its place, there was only fear.

“Our eyes deceive us sometimes, son,” Bill was telling Ricky. “They make us see things that aren’t really there. And sometimes they hide things that are there.”

“Yeah?”

“Oh yes. I wouldn’t lie to you. You know that.”

“Of course.”

“So it’s time your eyes told you the truth, don’t you think?”

“Sure.”

“Good,” Bill told him. “Now . . . are you ready?”

“For what, sir?”

“To see what the world really looks like, Ricky. Your attention is wandering. You’re not focused. Listen to me. We have a force of evil that will destroy us, right here in our midst.”

“Do we?”

“Open your eyes, and see for yourself.”

Ricky’s eyes flickered open and it was clear from the instant his eyes focused that his father’s tutelage had worked.

“Candy?” he said. “Where did you come from?”

“I’m not—”

“Shut your wicked mouth!” her father said, jabbing the air just a couple of inches away from her face. “Don’t listen to anything she says, boy. I told you they’re full of lies, didn’t I? It comes so easily to them. They open their painted red lips and the lies just start tumbling out! They can’t stop themselves.”

“What are you talking about, Bill?” Melissa said.

“You, woman.”

“Woman?”

“That is your gender, isn’t it?” Bill replied.

Candy saw the look of mystification on Melissa’s face. This sounded like her father, only worse.

“I don’t know what the hell—or who the hell—has got into you, but you are not my husband . . .”

“What’s happening?” Ricky said, with an edge of panic in his voice.

Bill pointed at Candy.

“You’re the reason this town has lost its way. Lost its mind. You brought freaks onto our streets so they can gain a hold on our world.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Candy said. “Whoever is still here was just left behind when the waters receded. I’m sure they all want to go home.”

“Home? Oh no. These deviants are never leaving this town. Except in coffins.”

“What?”

“How much plainer do I need to be? We are fighting a war against these invaders. My foot soldiers are ordinary men and women, who come to worship at my church, and have heard me speak. They’ve seen these freaks with their own eyes. They know they exist. Demons, from the bowels of hell!”

“No, Dad, they’re just lost people who want to get back home to the Abarat. Let me go back there and talk to the Council. They’ll find some way to peacefully get all the folks who were left behind out of your town without blood being spilled.”

“Did you hear her, Ricky? Folks, she called these demons. As though they were the most natural things in the world.”

“Yes, sir. I heard.”

“What’s to be done, Ricky? She’s your sister. If you tell me to be merciful, I will be. But be very certain. I don’t want to turn my back on her and find she’s using her magic against us. Just look at her. There’s nothing natural about her.”

“Why are you so interested in magic all of the sudden?” Candy said to her father. “You would’ve said anyone talking about that was crazy.”

“That was before I found my vest of many colors.” He ran his palm over the garment, and it responded to his touch. A ripple of pleasure ran through it, causing its designs to intensify.

“Hats!�

�� Candy said, suddenly remembering where she’d seen all the pieces of the patchwork before. “It was five beaten-up hats.”

Bill’s expression was glacial.

“Clever,” he said.

“I knew the person who owned them, Dad. Now he was bad. He murdered the people who owned those hats just so he could have them for himself.”

“Disgusting. You’re making all this up as you go along. Just like your mother. Lies, lies, and more lies. That’s all you women are capable of.”

“I swear,” Candy said. “That’s why he’s talking all weird, Mom. He’s got a little bit of Kaspar Wolfswinkel in him, because that was where his power was. In the hats he stole from the dead.”

“You’re not frightening me, if that’s what you’re trying to do,” Bill said. “Your sorcery won’t work on me. I think we should take her to the church, Ricky.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I don’t need your religion, thank you,” Candy said.

“You’re not getting any. You see, I’ve been having visions. Imagine that. Your drunken lump of a father, who everyone laughed at behind his back—”

“I never laughed, Dad. It was sad.”

“Shut your mouth! I don’t need your pity! I’ve built a machine.” He tapped the middle of his forehead. “It came from a vision. And I couldn’t understand what it was for. But now I know. It all fits.”

“Bill!” Melissa broke in. “Maybe we should listen to her.”

“No. A greater voice speaks to me. And I listen to it.” He paused, and for a moment closed his eyes. “Even now, it speaks. It’s telling me what it needs.”

“Oh yeah? And what’s that?” Candy said.

Bill’s eyes opened in an instant.

“You.”

Part Four

The Dawning of the Dark

No need to fear the beast

That comes alone to your door,

For loneliness will be its undoing

Nor need you fear those beasts

That hunt in packs.

They will die when divided from their clan.

Fear only the one

That does not come at all.

It is already here, standing in your shoes.

—The last sermon of Bishop Nautyress

Chapter 26

The Church of the Children of Eden

“CANDY? WE’RE ALMOST THERE.”

Even though Candy had told Malingo not to wake her, she surely couldn’t have meant him to leave her sleeping once they’d arrived. Still, he’d learned to be delicate when he was rousing her from sleep.

There was no great urgency. The ferry had only just sailed into Tazmagor Harbor. It would be several minutes before they docked. Even so, there was an unease among the passengers that was nothing to do with their arrival. Their voices were shrill, their laughter forced. Malingo knew why. There was a mysterious sense of foreboding in the air. Something was coming: something that wasn’t welcome. He had no more idea of the approaching something than the passengers who hurried past him. But it wasn’t good. His stomach was tied in knots, and there was an itch behind his eyes that he first remembered feeling the day his father took him to be sold. He did his best to put the itch and the unease out of his mind so as to concentrate on waking Candy. He put his hand on hers, and shook her gently.

“Come on, Candy. Time to wake up.” There was no response. He shook her again. “Come on,” he said, leaning toward her now. “You’ll have to finish this dream another time. Wake up.”

“I’m just dreaming this,” Candy reminded her father. “I don’t have to listen to you. I can wake up at any time.”

“Well you’d better not, because if you do”—he pointed to Melissa—“she is going to be the one who suffers.”

“Stop it, Bill,” Melissa said.

“Why? Because you think I don’t mean it? I mean it. Ask your daughter.”

“There’s stuff in his head right now he can’t control, Mom,” Candy said. “Somebody stronger might have fought against it. Dad just didn’t want to.”

“You’re going to regret that,” he said.

“Candy? What’s wrong?” Malingo asked her.

The expression on Candy’s sleeping face was no longer calm. A frown furrowed her brow, and the corners of her mouth were turned down.

“You’re starting to scare me,” Malingo said. “Why won’t you wake up? Can you even hear me?”

Did she nod her head? If she did it, was the tiniest of motions.

“Oh, Lordy Lou. What is going on? Please wake up.”

Now it seemed she shook her head, though the motion was as subtle as her nod. So subtle he wasn’t sure she’d moved her head at all.

“Is it that you don’t want to wake up right now?”

And again she nodded. Or at least he thought she did.

“All right . . .” Malingo said, doing his best to sound calm. “If you want to stay asleep, I guess that’s okay. There’s not much I can do about it anyway. You just keep dreaming. I’ll deal with things on this end.”

There was neither a nod nor a shake by way of response. Her face simply became more intensely troubled.

It was strange to be walking the streets of Chickentown again, even stranger to be walking them at her father’s side—though of course she was invisible to everyone but him—and to see people’s responses to him and how his reputation had changed in the time she’d been away. A few people were openly afraid of him. They either crossed over the street to avoid him or hurriedly ducked into stores. But others, seeing him coming, made sure to pay him their respects. Some simply nodded or offered a quick “good afternoon.” But not one of them was able to entirely conceal the unease they felt in his presence. A few of them actually called him Reverend, which Candy knew she’d never get used to. Reverend! Her father, the brutal alcoholic who beat his wife and children: Reverend! Her mother had been right: things had certainly changed in Chickentown.

Once they were off Main Street and there weren’t so many people to see him apparently talking to himself, he said to Candy, “Did you see how much respect I get?”

“Yes, I saw.”

“Surprised you, didn’t it? Didn’t it?”

She wanted to defy him even now. She wanted to tell him that it was all an empty illusion, and she knew it. But then she thought of her mother. The man at her side was capable of doing terrible things, she didn’t doubt it. So she answered him, “Yes. I guess it did surprise me.”

“But what you don’t understand is that these people are frightened. They can smell the freaks: the things that got washed into the streets and left here. And they’re afraid. What I do is take the fear away.”

“How?”

“None of your business. Salvation’s a very private industry. They pay for the privilege, I can tell you that. I don’t take a cent of it. All their contributions go back into the church. And everybody’s glad to give. I’m bringing some comfort and maybe some happiness back into their lives. That’s worth a few dollars of anybody’s money. Here we are. Home sweet home.”

He was talking about a plain, one-story brick building, now painted a garish green, which Candy must have walked past hundreds of times in her life. It had a big bulletin board on the small lawn at the front which bore a single message:

THE CHURCH OF THE CHILDREN OF EDEN

REVEREND WILLIAM QUACKENBUSH

WELCOMES ALL SINNERS IN NEED OF SALVATION

The member of The Sloppy’s crew who found Malingo and Candy still aboard fifteen minutes after the ship had docked, was, much to Malingo’s surprise and relief, another geshrat. Talking to one of his own people made the complicated business of explaining their situation a little easier. It became easier still when the ferryman said, “You’re Malingo, right?”

“Do we know each other?”

“No. I’ve just heard all the stories. My sister, Yambeeni, follows everything you and the girl do as best she can. There’s a lot of rumors. People invent things abou

t you I’m sure, just so they’ve got something new to talk about.”

“I didn’t realize anybody cared.”

“Ha! You’re kidding? You and Candy—is it okay if I call her Candy, or should it be, like, Miss Quackenbush or some-such?”

“No, I’m sure Candy would be fine.”

“I’m Gambittmo, by the way. Bithy, Mo, but usually Gambat. Like Gambittmo the geshrat, only shortened. Gambat Yoot.”

“It’s good to meet you, Gambat.”

“Can I ask you something?”

“Of course.”

“Could I get your autograph? It’s for my sister? She will flap her fins!”

Gambat demonstrated what was obviously a family trait by flapping his own orange fins, which were uncommonly large.

“Your sister would want my autograph?” Malingo said.

“Are you kidding? Of course. She’s a big fan. I am too, only it’s really the girls who go crazy. She knows all the details. How you saved Miss Quackenbush—sorry I can’t call her Candy, it just doesn’t sound right—from that crazy wizard guy, Wolfswinkel. We went to the house on Ninnyhammer, my sister and me. Saw all the stuff in the story. I mean, you can’t touch anything. It’s all roped off. But there’s the proof. It all happened. Oh, and maybe on the next page just something for me?”

Malingo accepted the notebook and then the pen, which had a small carved and painted copy of the Commexo Kid’s head on the end of it, grinning from ear to ear.

“Sorry about the stupid pen. A passenger left it. I hate the Kid.”

“Yeah?”

“That toothing grin. Like everything’s just dandy.”

“And it isn’t?”

“You ever met one of our people with money? Didn’t think so. We don’t have power, or money, or people to lead us. Why do you think we’re all talking about you?”

Malingo looked up at Gambat, searching his face for a hint of mockery. But he could find none. Candy’s head lolled around as she slept.

“Is Miss Quackenbush okay? Does she need maybe a doctor?”

“No, I don’t think so. She’ll be fine. She’s just tired. What do you want me to write?”

The Great and Secret Show

The Great and Secret Show Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story

Coldheart Canyon: A Hollywood Ghost Story Galilee

Galilee Cabal

Cabal The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus and His Travelling Circus Everville

Everville Books of Blood: Volume Three

Books of Blood: Volume Three Weaveworld

Weaveworld The Scarlet Gospels

The Scarlet Gospels Sacrament

Sacrament Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6

Books of Blood: Volumes 1-6 Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell

Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell Mister B. Gone

Mister B. Gone Imajica

Imajica The Reconciliation

The Reconciliation Abarat

Abarat Clive Barker's First Tales

Clive Barker's First Tales The Hellbound Heart

The Hellbound Heart The Inhuman Condition

The Inhuman Condition Infernal Parade

Infernal Parade Days of Magic, Nights of War

Days of Magic, Nights of War The Thief of Always

The Thief of Always Books of Blood Vol 2

Books of Blood Vol 2 The Essential Clive Barker

The Essential Clive Barker Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3

Abarat: Absolute Midnight a-3 The Damnation Game

The Damnation Game Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium

Tortured Souls: The Legend of Primordium Books of Blood Vol 5

Books of Blood Vol 5 Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator

Imajica 02 - The Reconciliator Books Of Blood Vol 6

Books Of Blood Vol 6 Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion

Imajica 01 - The Fifth Dominion Abarat: Absolute Midnight

Abarat: Absolute Midnight The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus

The Adventures of Mr. Maximillian Bacchus & His Traveling Circus Tonight, Again

Tonight, Again Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1

Abarat: The First Book of Hours a-1 Books Of Blood Vol 1

Books Of Blood Vol 1 Age of Desire

Age of Desire Imajica: Annotated Edition

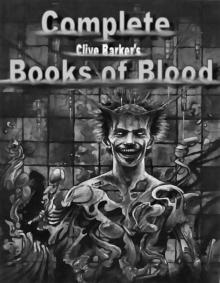

Imajica: Annotated Edition Complete Books of Blood

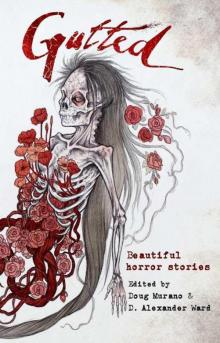

Complete Books of Blood Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories

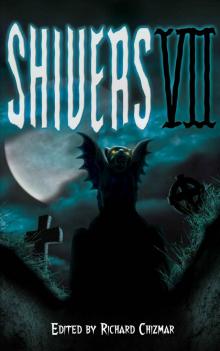

Gutted: Beautiful Horror Stories Shivers 7

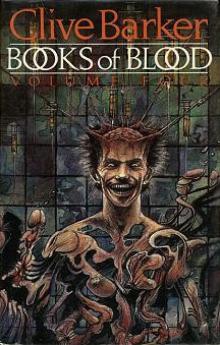

Shivers 7 Books Of Blood Vol 4

Books Of Blood Vol 4